- INTRODUCTION

- LECTURES

- Critical practices in the Architecture of the Baltic Region / An Introduction by Lolita Jablonskienė

- Ieva Zībārte / Uncensored Admiration. 10 Quiet Forms of Dissidence in the Life and Work of the Architect Marta Staņa

- Ingrid Ruudi / Critical Architecture between Prestroika and Independence? GROUP T Architects in Tallinn

- Marija Drėmaitė / Critical Practices in Lithuanian Architecture of the Soviet Period

- Andres Kurg / The Papers, Exhibitions and Buildings of the Tallinn School in Estonia

- Ivan Ristić / Bogdan Bogdanović – the Practice of Architecture under Changing Political Regimes in Yugoslavia

- INTERVIEWS

- ESSAYS

- Tor Lindstrand, Håkan Nilsson / Staging Subversive Opportunism in the Age of Feedback Loop

- Manuel Bürger / Slipping Through Templates. Limitation as a Tool of Control - A Design Observation

- Ethel Baraona Pohl / Emancipatory Architecture

- Jack Self / The Only Task of Architecture

- Eray Çayli / Turkey’s Construction Boom as Opportunity and Publicness as Medium of Subversion

- ABOUT

Image: Posconflicto Laboratory

David Greene wrote in 1969 an article entitled Are you sitting uncomfortably? Then I’ll begin and the same quote can be used to describe the feeling that has been a catalyst of the current transformation in architectural practice. In the same article Green states that "The future doesn't exist, now does it? Do it now." and this seems to be the guideline that is leading the huge amount of collective processes based on the swarm intelligence, which is emerging from the citizenship and taking place in the public space, both in the urban environment and in the architectural practice nowadays.

Traditional ways of resistance are now related with the notion of insurrection that is explained by the Invisible Committee as movements that do not spread by contamination but by resonance. This is the way that architecture movements are fighting to transform the practice from its very basis, to use the opportunity of being in the right place at the right time. The era of radical neoliberalism, years of pervasive capitalism, political crisis, and pseudo-technological developments are the perfect stage for a real insurrection, capable of introducing a radical shift in the way we think and practice architecture. And this is happening now, with several small or medium practices seeking to provoke real structural changes by creating renewed political and economic discourse.

In this vast new territory, the shift in the way that architecture is understood has been influenced by the revolution in the social and political field, which in its latest stage started in 2011 with the Arab Spring, 15M, Occupy Wall Street, and this spirit has been kept alive, as we can see now with the events in Ferguson [St. Louis, Missouri] or happening now ‒ as I am writing these words ‒ at the #umbrellarevolution in Hong Kong. Within this context, architects must take action and help to build a commonplace apart from the establishment. It’s worth recalling the words of Lebbeus Woods in an interview by Sebastiano Olivotto:1

“Paul Virilio and I, in our different ways, share an intense interest in the changes brought about by technological innovation, by cultural and social upheavals, by natural catastrophes like earthquake and the social and architectural responses to them. I see these extreme cases as the avant-garde of a coming normality, one that we must engage creatively now, inventing new languages, rules and methods, if we are to preserve what is essential to our humanity, that is, compassion, reason, independence of thought and action.”

Following the recent years of pervasive downturn in the economy, sparking both a political and an ethical crisis, several clear manifestations of these crises have emerged, as can be witnessed by the proliferation of abandoned buildings across Spain, the increase of unemployment and the disaffection for traditional democracy prevalent all over the EU. But after four years of grassroots resistance in several European countries [Spain, Portugal, Greece, among others], new ways of reclaiming the right to the city are emerging. In this context ‒ what Lebbeus Woods calls ‘an avant-garde of coming normality’ ‒, the necessity to break some limitations, intrinsic in the understanding of what architecture is, is stronger than ever. The role of the dissident architect appears not as a figure of resistance but as an opportunist who understands his/her context and decides to react and adapt in a Darwinian sense, where not the strongest but the most flexible species succeed.

On the understanding that the world is complex, the responses and projects that shape these new movements go beyond trendy concepts such as 'smart cities' or 'the city as a laboratory', and rather than focus on a simple participatory theory, they look for a pragmatic practice which introduces the notions of political dissent, swarm intelligence and the commons as an important basis for their active implication on finding real answers following the political and financial crises, the real estate bubble and the never-ending discourses of austerity and scarcity. This metamorphosis in the architectural practice has resulted in new ways of working using open source platforms, going from the DIY approach to the DIWO (Do-it-with-others) approach, harnessing new technologies to enhance communication and dialogue as an architectural tool, accompanied by innovative economic models that have emerged in recent years, such as crowdfunding, micropayments and social money. In this context, the possibilities are endless.

Collective movements and emerging experiments in public space, housing and the right to the city are envisioned as tools, not as ends in themselves. Additionally, there is the internet, which represents an unprecedented instrument for the world in flux that we are living in. This state of the world has been clearly defined by Michel Foucault, “We are in the epoch of simultaneity: we are in the epoch of juxtaposition, the epoch of the near and far, of the side-by-side, of the dispersed.”2 Based on that, and as a reaction to the crisis of contemporary cities, the remarkable projects are the ones that are working from a bottom-up strategy, but far away from trends or ephemeral initiatives, they are engaged in profound research and taking action to provoke that structural change we are claiming for the system. If we decided to draw a map of the initiatives that are working with this approach, the result could be connected with the ideas that Frederic Jameson outlined in his book Archaeologies of the Future,3 by exposing that “our imaginings are all collages of experience, constructs made up of bits and pieces of the here and the now”. Following on from this idea it is fundamental to recognize that we are now tracing paths to the future, ones composed of all these pieces segregated into a terra incognita that is the territory to envision new scenarios for the practice.

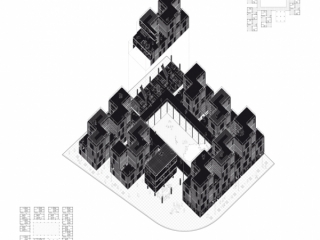

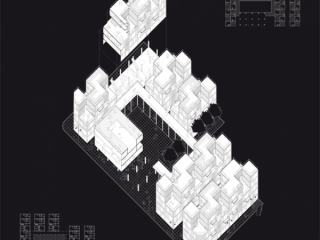

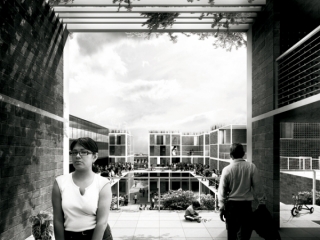

Image: Posconflicto Laboratory

These new scenarios are emerging beyond any geographic or temporal limits. In Guatemala, the Posconflicto Laboratory project is a long-term research platform that aims to uncover how tactical architecture might address the imbalance between housing and land ownership. By questioning the idea of the political and the significance of architecture, they attempt research around the topic of space production, focusing on housing as a first step. This way, with an inter-institutional and transdisciplinary approach, it is possible to work on the notions of dwelling and public space as complementary elements of the urban landscape. Guatemala was immersed in an internal armed conflict for more than thirty-six years [1960-1996], which provoked an enormous inequality in economic and social terms, basically between the indigenous migrants that had arrived in Guatemala City during those years. This community is the focus of the project, which is wide and is envisioned to be developed in different steps, dealing with sensitive problems related with armed conflict, working conditions, military and political repression, internal migrations, and segregation. As an example of using architecture as a projective mediating device, able to provide tangible, inclusive and credible possibilities for the production of common spaces, they call on the experiences of self-managed cooperative housing in South and Central America, where the movement’s organization focuses on the struggle for housing as a human right and not as a commodity, with collective ownership of property as a cornerstone. As the team states, for the idea of rethinking the political, starting from the scale of architecture as a territorial project, it is useful to understand that architecture as a project, in its process and form, can significantly contribute to building an alternative ethos based on communal modes of trust building and solidarity.

Forensik Mimarlık, research photos and works, Mardin Univerity. Architecture Faculty, Mardin, 2014

Based in Turkey, Forensik Mimarlık was born as an architectural pedagogical experiment that drives its courses and programmes and was inspired by the forensic methodological research in conflict zones that was initiated by Forensic Architecture lead by the architect Eyal Weizman and his team. The important relationship between academy and practice is emerging once again, after years of the commodification of education itself. We have been able to see, through the research of Radical Pedagogies,4 how important this relationship has been for the understanding of architecture as an expanded field and its interaction in other disciplines. Thus, it is worth underlining the work of Forensik Mimarlık, which is based in the south Kurdish region of Turkey, a conflict zone due to the intense civil war that had raged between the Turkish government and the Kurdish movement. The academic programme involves the observation of how a territory has been officially defined as tabula rasa by hegemonic structures and needs to be analyzed and decolonized by a new conceptualization with concrete cases. The increasing number of refugee camp settlements that have expanded in this land is the starting point for a wider research on politics and the economy, intended to focus on architecture as a response to the needs of migrant people who arrive at these settlements; it searches for future design proposals for this territory, which is currently undergoing rapid urbanization.

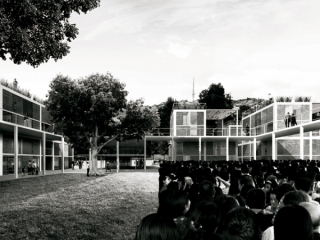

Museo aero solar. Image: FAST

In 2004, the architectural think-tank FAST, directed by Malkit Shoshan, announced its first project, One Land Two Systems, for Ein Hawd, an unrecognised Palestinian village in Israel, calling for a sustainable planning solution for the village. After more than ten years of intense work with the local community, FAST have recently published the results of two long-term projects: One Land (the construction of the first community building and a series of public events) and Platform Paradise, an art show commissioned by FAST and curated by Maurizio Bortolotti. The new master plan for ‒ and with ‒ the Palestinian village was created within these two projects, based on a scheme which started from an international architecture and design competition, and evolved until the village had been transformed into an artists’ village for a week, mitigating the gaps between spatial planning and reality and enhancing the community’s ability to actively take part in the process. The results of having a map, a visualization of the territory and the creation of a new spatial identity, transformed the perception of the residents and empowered them to participate in its further development by collaborating on the design of the master plan. These efforts have been fertile soil in which the local community worked together with a group of artists to create an extraordinary story of culture, history, art, and architecture. At the current time, the Ein Hawd residents are using the project to negotiate with the authorities to have Ein Hawd fully recognised by the state. In FAST’s own words, “the process has acted as a model for a new kind of architectural practice, based on community, sustainability and politics.”

The long-term engagement and on-going results of these three case studies makes it possible to think that architecture indeed can be a catalyst for structural change. The first reaction to the financial crisis in 2008 was marked by the oversaturation of pop-up or bottom-up projects, especially in the public space and made by different agents, not always architects. Blogs, social networks, and specialized websites were focused on spreading what rapidly became a new trend ‒ the concept of tactical urbanism. Without money and after the struggles and upheavals they had been through, many architects started working together in a collective way, reusing materials to transform the streets into public spaces or to create spaces for exchange and leisure. The use of technology and social networks to create a diffuse territory between the physical and the digital was studied under the concept of sentient city and rapidly appropriated by the neoliberal market with the notion of smart cities. The idea of living in “a city that can remember, correlate, and anticipate,"5 is too strong to be dismissed, and urban design in recent years has been based on this driving force. It seems that a wave of techno-optimism has been at the foundations of every single independent project built on this context and a significant amount of proposals have been based on the use of the tools instead of trying to change the basis of the problem. Crowdfunding, 3D printing, and digital fabrication can be found at the core of the so-called most innovative proposals, but these kinds of proposals have not always been the most successful in transforming and enriching the daily life of citizens.

These years ‒ from 2008 until 2011 ‒ were important in creating awareness about the architect's role and the need to adapt to a new state of the world... but after this, what comes next?

Aside from being critical towards some trends and pop-up projects of the so-called ‘tactical urbanism’ approach, it is important to highlight that it was their emergence and fast response to a particular situation, and the spontaneous spirit behind them, which formed the basis for an important shift, offering the opportunity to test, evaluate and transform some of the preconceptions of the ‘future of architecture’. The biggest challenge at this point is to go further than ‘trial and error’, beyond the ephemerality of tactical urbanism and to search for strategic processes that can provide an answer to the question of how to address real changes in the built environment. Can we use architecture as a form of resistance and subvert the current political system? Going back to Lebbeus Woods’ The Resistant Checklist, it is important to recall his writing: “The word resist is interestingly equivocal. It is not synonymous with words of ultimate negation like ‘dismiss’ or ‘reject.’ Instead, it implies a measured struggle that is more tactical than strategic. Living changes us, in ways we cannot predict, for the better and the worse. One looks for principles, but we are better off if we control them, not the other way round. Principles can become tyrants, foreclosing on our ability to learn. When they do, they too must be resisted.”

In this sense and by the understanding that there are two ways of ‘resistance’, one from outside the institutions and the other from the inside, one of the most important approaches of the kind of practices we are describing here is that they are striving to create a renewed political and economic discourse by working together with (not for) institutions and governments. This way, the work schemes proposed from these new subversive opportunists are creating a new position in the political field for the architectural practice, based on a long-term vision and finding the balance between bottom-up and top-down strategies.

Then, these resistant acts can be related with the notion of emancipatory architecture, not only in the traditional meaning of the word emancipation ‒ the fact or process of being set free from legal, social, or political restrictions; liberation ‒ but thinking of what the author Rancière mentions in his book The Ignorant Schoolmaster,6 considering equality as a starting point rather than a destination. He wrote that “Whoever teaches without emancipating stultifies. And whoever emancipates doesn’t have to worry about what the emancipated person learns. He will learn what he wants, nothing maybe.” Perhaps we can stop here and focus again on architecture. The three projects we have mentioned before can be understood as emancipatory architecture: it is architecture that has replaced the image of the isolated architect, the solitude of the hero, with the unique response to a certain need. Emancipatory architecture follows the notion exposed by Nicholas Negroponte in the late 1960s, “Architects design the question, not the response."7

1. htttp://lebbeuswoods.wordpress.com/2010/04/21/as-it-is-interview-with-lebbeus-woods-1/

2. Michel Foucault, “Of Other Spaces, Heterotopias”, in: Architecture, Mouvement, Continuité 5 (1984): 46-49.

3. Frederic Jameson, Archaeologies of the Future: The Desire Called Utopia and Other Science Fictions, Verso Books, 2005.

4. Radical Pedagogies is an ongoing collaborative research project set up by Beatriz Colomina together with PhD students at the Princeton University School of Architecture. Radical Pedagogies focuses on radically new models and experiments in architecture education in the second half of the 20th century. Part of the Monditalia section at the 14th International Architecture Biennale in Venice, it has been awarded with a Special Mention. radical-pedagogies.com

5. Mark Shepard (ed.), Sentient City. Ubiquitous Computing, Architecture, and the Future of Urban Space., MIT Press, 2011.

6. Jacques Rancière, The Ignorant Schoolmaster, Stanford University Press, 1991.

7. Carlo Ratti, Matthew Claudel (eds.), Open Source Architecture, Einaudi, 2014.