sss

Tonight we will be discussing projects from the journal Scapegoat: Architecture, Landscape, Political Economy, where both Dr Turpin and I are founding editorial members and contributors. Scapegoat is an independent, not-for-profit, bi-annual journal designed to create a context for research and development regarding design practice, historical investigation, and theoretical inquiry. Our editorial board is made up of seven members distributed internationally. While the magazine is at the core of our efforts, we also take part in exhibitions, symposia, organize dance parties, dinners, and goat roasts. It is important to note here that while we are speaking about projects featured in Scapegoat, we don’t speak for other editors who are not here tonight – our description of the project is not necessarily shared by all members of the editorial board.

We should begin with the name: Scapegoat. As a mytheme, the figure of the scapegoat carries the burden of the city and its sins. Walking in exile, the scapegoat was once freed from the constraints of civilization. Today, with no land left unmapped, and with the processes of urbanization central to political economic struggles, the scapegoat is exiled within the reality of global capital. The journal examines the relationship between capitalism and the built environment, confronting the coercive and violent organization of space, the exploitation of labour and resources, and the unequal distribution of environmental risks. Throughout our investigation of design and its promises, we return to the politics of making, as a politics to be constructed.

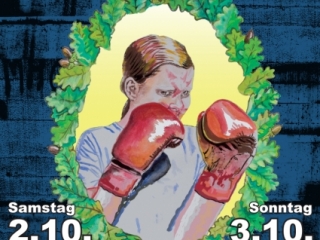

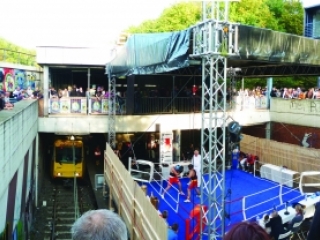

Scapegoat: Architecture/Landscape/Political Economy event posters. Courtesy of Chris Lee and Adam Bobbette

Scapegoat: Architecture/Landscape/Political Economy event posters. Courtesy of Chris Lee and Adam Bobbette

As a project that consistently tries to understand what it means to intervene in the contemporary context of making, we find a historical resonance with the work of Walter Benjamin, the early 20th century German philosopher and critic. In 1928, Benjamin published One-Way Street, where he broke dramatically from the conventions of academic criticism and literary journalism. He positioned himself in the avant-garde by adopting a form of writing that interfered with popular capitalist modes of expression such as the newspaper and street side advertisement. Benjamin begins his text by announcing the intentions of the book as follows: “The construction of life is at present in the power of far more facts than of convictions, and of such facts as have scarcely ever become the basis of convictions. Under these circumstances . . . significant literary effectiveness, can come into being only in a strict alteration between action and writing; it must nurture the inconspicuous forms that fit its influence in active communities better than does the pretentious, universal gesture of the book – in leaflets, brochures, articles, and placards. Only this prompt language shows itself actively equal to the moment. Convictions are to the vast apparatus of social existence what oil is to machines: one does not go up to a turbine and pour machine oil all over it; one applies it a little to hidden spindles and joints that one has to know”.

Benjamin captures the necessity for formal invention, experimentation, and the specificity of commentary for social criticism to be effective. Scapegoat is printed on cheap paper, in matte black and white, in layouts that come off in turn as real estate advertisements, posters, and academic essays. The design shifts page orientations and creates atypical rhythms. If there is a complex repetition (we will come back to this) of Benjamin’s insistence on formal inventiveness in order to circulate within “an active community”, we are also driven by the necessity to apply conviction to those little spindles and joints that we have to know.

Form & Type

In the Summer 1978 issue of Oppositions: A Journal for Ideas and Criticism in Architecture, the publishing organ of the New York based Institute for Architecture and Urban Studies, Rafael Moneo, a practicing architect, theorist and historian, published an essay on the two-hundred-year history of the concept of type in architecture. His purpose is explicit, to recuperate a theory of type for the present. Without a coherent theory of type, he warns, architecture is under threat of both a historicism and formalism without content, a ceaseless production of meaningless new forms. A recuperated theory of type will produce, on the contrary, a method of design that allows the architect to meaningfully position the architectural object in relation to the city and its history. “Architecture”, he states, “is not only described by types, it is also produced through them.” The architect, he continues, “is initially trapped by the type because it is the way he [or she] knows. Later he [or she] can act on it; he [or she] can destroy it, transform it, respect it. But he [or she] starts ultimately from the type.”

The concept of type describes a generic set of structural regularities repeated across time and space. Moneo provides a simple example ‒ the hallway. The hallway is a consistent type whether it is in a courthouse, an apartment or a house. The plaza too appears in New York’s Upper West Side, Lower East Side, Venice or Hong Kong. While the type is defined by its repeatability, it never repeats in the same way. A type can only be actualized through mutation. Therefore, there is no such thing as a pure type, whenever a type touches the ground, so to speak, it is deformed.

But how do we characterize this deformation? Aldo Rossi, the interlocutor to whom Moneo is responding in the text I just quoted, had already advanced a theory of type and its modification in his book The Architecture of the City (1966). For him, what generates typological mutation is the “locus”, that is, the singularity of place and of practice. It is the source of the messy stuff that complicates any simple repetition of the type. The locus, he says, is the “singular artefact determined by its space and time, by its topographical dimensions and its form, by its being the seat of a succession of ancient and recent events, and by its memory.” For Rossi, architecture is the physical mark of practices. Practices singularize and specify the type. The built object is activated, modified, and inflected by practice. It is only through practices that architecture becomes locally meaningful.

Forms Of Life

We were asked to recommend a reading and one of the connections that we made both through the journal and through our own research is coming through Aldo Rossi and other Italian radicals in the sixties and seventies and that line reading through the autonomy all the way to contemporary practice and relationship to Tiqqun and other French activists. So I will say a bit about Tiqqun before we discuss projects from Scapegoat.

In the Introduction to Civil War, Tiqqun, which is both a French journal – part of which is translated under this title but many other texts exist as well as an anonymous collective, which publish the journal, and the historical process to which these texts bear witness (CW 7). Tiqqun call on us to take sides, to make decisions, and to uphold our convictions not unlike Walter Benjamin. Tiqqun also refers to someone who “triggers or pursues the process of ethical polarization, the differential assumption of forms of life”. And so what we are doing is trying to bring a relationship of Rossi’s sense of the locus and locally meaningful specificity into a relation with the context of forms of life.

One key to understanding Tiqqun’s ethic of polarization is the need to replace the generalized hostilities conjured by the desire to annihilate Empire with the clear decisions of friendship and enmity. This may be the subtlest dimension of the book, and certainly it is one of the most important: the ethic of civil war is not one of annihilation or destruction, but of political composition. This is important to Tiqqun because “Empire does not confront us like a subject, facing us directly, but like an environment that is hostile to us”. From such a position, the foundations of any representational politics are pragmatically suspect.

Tiqqun have indeed been criticized for their strict refusal of identity politics, but the provocation cannot, despite its rhetorical style and intellectual polemics, be simply dismissed. What is most important to recognize is that the text operates according to a strategy of intervention – literally, a coming between. It attempts to come between us, where a plurality of forms of life are connoted by the term “us.” The most consequential of these connotations for architects and for artists is the denial of any position of neutrality between us. Tiqqun’s virulent denial of neutrality at issue in both the analysis and diagnosis is as emphatic as the hope for neutrality is naïve. Tiqqun’s Introduction to Civil War is indeed remarkable in its ability to dispel, at every turn, any assumption that there is a space or position of neutrality that might administer, judge, or decide among competing forms-of-life according to some universal criteria of acceptability.

The ethic of polarization that Tiqqun, following Walter Benjamin, poses as a problem is a clear one: how do we find each other? This is a lesson that architects and designers might consider more closely in their work to contest the gentrification (i.e. destruction) of our cities, the quotidian forms of urban planning violence, and within the larger campaigns against the neoliberal agenda of capitalism. It is, in fact, what comes between us and what might help embolden the formation of new communities of solidarity, new ways of constructing and composing and building together, to survive the hostility of this collapsing Empire. Let us be very clear on this point: the ethic of civil war is an ethic of relation to build new relationships among allies working in different fields outside of the register of representational politics, it does not need to wait for governments to fail, banks to go bankrupt or new agreements to be signed.

In fact, in her interview with Scapegoat, the French philosopher of science Isabelle Stengers describes her own concept of pragmatism of practices as “exactly like Tiqqun’s concept of ‘forms of life.’” However, she is quick to stress, “no form of life is exemplary. The interstice [the in-between] is not associated with anything exemplarity, and has nothing messianic about it. Rather, its mode of existence is problematic.” That is, for Stengers, each form-of-life can be taken as certain ‘problem fields’ within which our form of life can flourish, change, adapt, and invent itself again.

In what follows, we develop six typologies of practice, or architectural forms-of-life NOT to describe them as messianic promises or a ‘selection of the chosen.’ Instead, our goal is to advance a typology of practice that, as Stengers suggests, “are concrete situations which become political precisely because of the way in which they are lived and from the type of force that they require.” So I’m going to talk about a few of the first types in relation to projects published in the last several years.

Typologies Of Practice

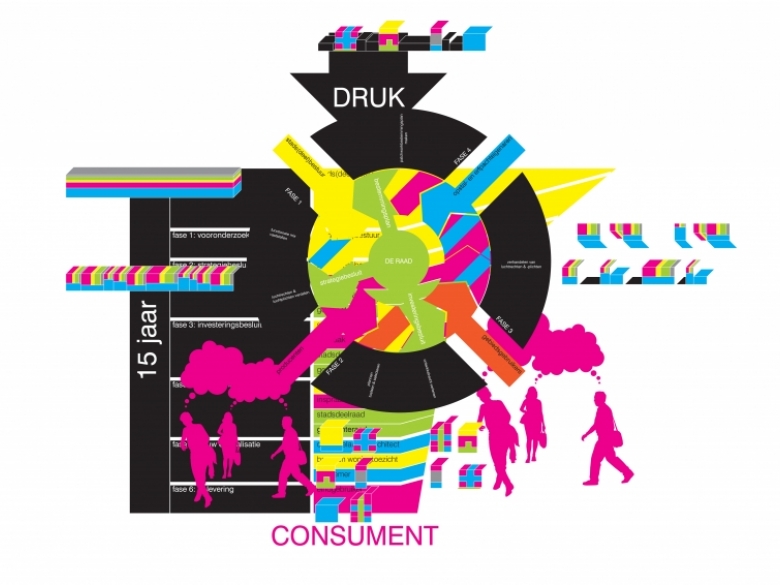

01 Graphic Appropriation

Scapegoat does not recognize the usual distinctions between graphic design, architecture, landscape, and political economy. We try to feature practices that appropriate the graphic to construct narratives that cross the borders between these disciplines. Issue 02 features a piece by Société Realiste, a French practice which in their words “works with political design, experimental economy, territorial ergonomy and social engineering consulting. [As a] polytechnic, it develops its production schemes through exhibitions, publications and conferences.” This work is exemplary for the practice type we will call GRAPHIC APPROPRIATION.

This project appropriates the 1949 film The Fountainhead, by King Vidor and based on Ayn Rand’s 1943 novel of the same name. The central hero of The Fountainhead, as you may know, is an architect, Howard Roark, which Rand uses as a type through which to speculate on the virtues of individualism as a personal ethic. In one of the final scenes of the film Roark is on trial for dynamiting one of his own buildings, a social housing project in the International Style and situated by implication in New York City. The residents had modified the building by adding balconies to suit their comfort, against the initial design of the architect. In front of a jury, Roark defends his actions thus: “No work is ever done collectively, by a majority decision. Every creative job is achieved under the guidance of a single individual thought. An architect requires a great many men to erect his building but he does not ask them to vote on his design. They work together by free agreement and each is free in his proper function. An architect uses steel, glass, concrete, produced by others but the materials remain just so much steel, glass and concrete until he touches them. What he does with them is his individual product and his individual property. This is the only pattern for proper co-operation among men.” (The Fountainhead)

Continuing in the same vein, he later claims that, “I am an architect, I know what is to come by the principle on which it is built.” Keeping this in mind, this is how Société Realiste describe their own project: “From the original studio movie telling the story of a Promethean modernist architect . . . Société Réaliste has removed the sound and deleted every human presence to reduce the film to its decorum, its ideological architecture. As an echo of the disappearance of the topic of the film, Société Réaliste has recently designed Commonscript, a series of 48 panels . . . melding emptied videograms extracted from The Fountainhead, showing various views of the central location in the original film, in “Prime City” (read New York), with inscriptions extracted from the original script of the 1949 film. These sentences are ideological statements made by the hero of the film, but in this work, Société Réaliste has systematically replaced the possessive with the plural. Turning an autonomous discourse into a generalized one, undermining the description of a world deprived of its actors. So where you see “they” it reads “I” in the original film”.

‘Common Script’, Scapegoat: Architecture, Landscape, Political Economy 01: Materialism (2011). Image courtesy of Société Réaliste

‘Common Script’, Scapegoat: Architecture, Landscape, Political Economy 01: Materialism (2011). Image courtesy of Société Réaliste

02 Mutual Aid

We decided that our inaugural issue should examine the centrality of the problem of property because it is the literal foundation for all spatial design practices. This buried foundation must be exhumed. Architecture, landscape architecture, and urban design each begin with a space that is already drawn, organized, and formed by the concrete abstraction of property lines. From our perspective, property stands as the most fundamental, yet underestimated, point of intersection between architecture, landscape architecture, and political economy. What is a “site” except a piece of property? What are architecture and landscape architecture but subtle and consistent attempts to express determined property relations as open aesthetic possibilities? And, decisively, how can these practices facilitate other kinds of relation?

Mutual aid is rarely discussed amongst architects, much less placed as the base and goal of their practice, nevertheless MUTUAL AID is the second practice type we will discuss tonight. Usina, a Sao Paolo-based group of architects, does exactly this. Upsetting the typical client – architect or producer-consumer hierarchy, Usina’s mandate is to make city-making a horizontal process, as they make explicit, all forms of building are conditioned by the type of organization that bring it into existence. They write that: “In Brazil, mutirao gestinario, the housing policy of self-managed participatory mutual aid, was institutionalized during the first Labour Party administration in Sao Paulo. Usina was born at the same time to provide support and multi-disciplinary expertise to community-led initiatives and housing cooperatives. This approach aims to encourage collectively organized communities through the construction of public housing and related programs. “We are seeking a different format for city-making.”

A Workers Collective in Collaboration with Popular Movements, Scapegoat: Architecture, Landscape, Political Economy 01: Service (2011). Image courtesy of USINA

A Workers Collective in Collaboration with Popular Movements, Scapegoat: Architecture, Landscape, Political Economy 01: Service (2011). Image courtesy of USINA

Usina works with public housing recipients from the beginning of the construction process. Through non-hierarchical forms of consultation they work with participants to develop a plan and layout of a house or apartment, while managing the difficult constraints of building. Participants choose materials and building techniques “not based on financial return but on their quality and workability.” “Command over the whole process has a very clear political-economic effect: the concrete experience of self-management.” While Usina provides architectural expertise, their other role is organizing self-managed workers cooperatives. They argue that their process dramatically transforms the following characteristics of architecture:

1) Hierarchy: By including non-specialists and end users in the construction process destabilizes the traditionally rigid hierarchies of construction. As they state, “each agent may contribute and all workers are, and feel, necessary.”

2) Denaturalization of Process: Any issues which emerge during the construction process are managed on site through the principles of self-management. This approach makes all aspects of the construction of buildings visible and open to all members.

3) The right to final product: “When a worker uses what they make” states Usina “there is a greater sense of responsibility for the final product. This is unlike capitalist relations of production where the worker is violently alienated from what he makes.”

03 Unvalue

The third practice type I’m going to talk about comes from the work of Andrew Herscher who was formerly the UNESCO war crimes investigator in Kosovo and has recently moved to Michigan where we are the colleagues at the University of Michigan. He started the project called The Unreal Estate guide to Detroit which we’ve published in the first issue. You can get the first issue online on the website as a single pdf file for free. I think this in particular is a very important piece of work.

‘The Unreal Estate Guide to Detroit: Properties in/of/for Crisis’, Scapegoat: Architecture, Landscape, Political Economy 00: Property (2010). Image courtesy of Andrew Herscher

‘The Unreal Estate Guide to Detroit: Properties in/of/for Crisis’, Scapegoat: Architecture, Landscape, Political Economy 00: Property (2010). Image courtesy of Andrew Herscher

Under the concepts ‘unvalue’ I’d like to just unpack this project. I’m not sure how familiar any of you are with Detroit. It’s a city of approximately 60 percent vacancy at this point and quite a peculiar urban condition. What Andrew has tried to bring out is that rather than thinking of this as capital having flood the city, we can actually think of it as a set of values which have changed over in the concept of Detroit. And so the question he asks is, “what if what has also been lost in Detroit is the capacity to understand new urban conditions, conditions in which value is no longer structured economically, in the terms of free-market capitalism, but in wholly other terms? What if Detroit has not only fallen apart, emptied out, disappeared and/or shrunk, but has also transformed, becoming a novel urban formation that only appears depleted, voided or abjected through the lens of conventional urbanism? What if property in Detroit has not only lost one sort of value but has also gained other sorts of values, values whose economic salience is absent or even negative?” From this perspective certain values that could not be seen by the investment and the real estate speculation context of the city of Detroit are in fact unreal or undoubted.

According to Herscher’s analysis “Unreal estate” is a conceptual framework for exploring new, 'unreal' propositions, and thereby reconsidering the cultural agency for both artists and architects in the moments of urban crisis. For Herscher the values of unreal estate are unreal from the perspective of the market economy ‒ they are liabilities, or UNVALUES that hinder property’s circulation through that market. But it is precisely as property is rendered valueless according to the dominant regime of value that it becomes available for other forms of thought, activity and occupation ‒ in short, for other value regimes. Thus, the extraction of capital from Detroit has not only yielded a massive devaluation of real estate but also, concurrently, an explosive production of unreal estate, of “valueless” urban property serving as a site of, and instrument for, the imagination and practice of alternative urbanisms.” And so in the piece in Scapegoat he goes through the number of projects that have added up to the unreal estate agency and brings together such projects that are a series of at least four square blocks of houses that have been occupied by giant art installations. But there’s a point which is really important for us. One of the reasons why we’ve been working with Andrew is that he made the claim that Scapegoat is one of the few architectural publications that doesn’t talk about politics. According to Herscher, when he hears someone talking about politics it means that they are going to say something absolutely banal.

I just wanted to mention that the reason why we bring up this question about political economy is primarily related to the work of Jonathan Nitzan and Shimshon Bichler, who are two political economists working on issues related to Israel but have also written a number of articles more related to what they call the power theory of capitalism. For them production is always a societal activity and this is the really important place where architecture comes in and it helps to frame the other project as well. They draw on the work of the city theorist Lewis Mumford, who says that in fact “capital could be likened to a ‘mega-machine”. Nitzan and Bichler agree with Mumford in the sense of that: (and this is regarding the project of architecture. I think it is a really consequential passage for thinking about what does the architect do to create value), quote: “Tracing the long historical link between technology and power, Mumford argued that early machines were made not of physical matter, but of humans. In the great deltas of Egypt, Mesopotamia, China and India, the first feats of mechanization were achieved through the formation of giant social organizations. The visible output of those early mega-machines was massive public works, such as palaces, citadels, canals, and pyramids. These, though, were largely the means to an end. Indeed, according to Mumford, the true purpose of the ruling king and priests was the very assembly, operation, and control of the mega-machine itself.”

So if we were to extend this concept and a reading of history to the contemporary context and were to say how we relate this concept to the contemporary business world, Nitzan and Bichler would argue that “the earlier elite association of kingship and priesthood has now been replaced by a coalition of capitalists and state officials, overseeing a new mega-machine named capital. The visible ‘output’ of this new mega-machine is profit, but that is merely a codeword of power. What is being accumulated is neither future utility nor dead labour, but abstract power claims on the entire process of social reproduction.” The point here could not be more important for our work and what we are researching and the kinds of projects we are bringing out but it is the one misunderstood by people who are trying to do political work and economic analysis: “the power that is accumulated is not indexical to dead labour or to machines, but is instead related to the relative degree of control to shape the social field itself.”

04 Historical Appropriation

The next is a fourth type of work we have been trying to promote in our practice and is related to decolonization. Here a particular Canadian context comes out where the number of our colleagues in the geography faculty of the University in Toronto have been involved in this project, such as the Toronto-based geographer Shiri Pasternak, whose text “Property in Three Registers,” appears in the first issue of Scapegoat and tries to deal with the question of the conception of property that would not be derived from the Western European model. For her, what’s absolutely fundamental in the research in the solidarity work among the Algonquins of Barriere Lake, who live on unceded Alogonquin territory located approximately three hours north of Ottawa ‒ Canada’s Capital, is that the assumptions we make about property in which they form the land use can be dramatically tempered by reading of an Aboriginal title and the sense of property use. For her position, comparing property to a form of expropriation in the terms of land use or a form of capitalist alienation, she looks to the concept of property as a kind of taking care that represents a set of practices “that govern peoples’ relationship to the land through forms of entitlement based on taking care of the land for future generations.” So the future intergenerational responsibility is something that can be easily overlooked in the context of the Western model of inheritance in relationship to a broader set of concerns.

‘Property in Three Registers’, Scapegoat: Architecture, Landscape, Political Economy 00: Property (2010). Image courtesy of Shiri Pasternak

‘Property in Three Registers’, Scapegoat: Architecture, Landscape, Political Economy 00: Property (2010). Image courtesy of Shiri Pasternak

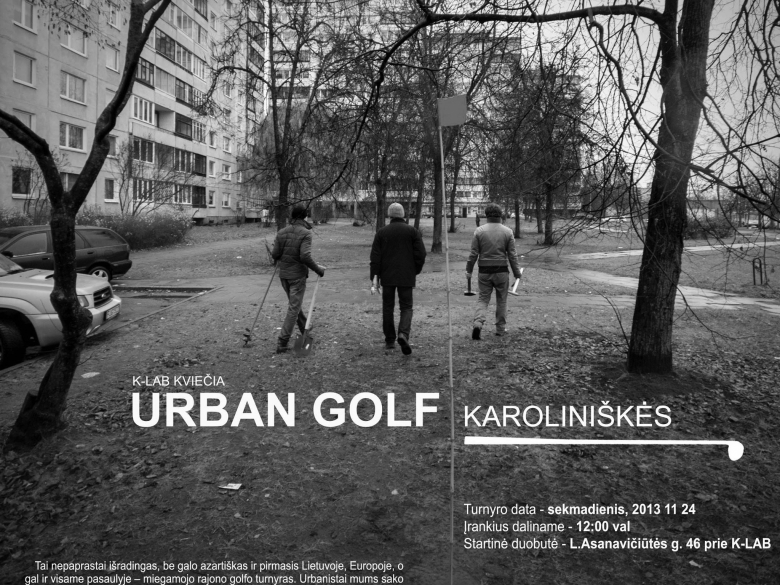

This is something particularly important that we have found in the interview with Gediminas Urbonas. Historical Appropriation. To examine the practice type we are calling historical appropriation, we turn to the main character of “Pro-testo Laboratorija Lietuva” by Gediminas and Nomeda Urbonas: the Cinema Lietuva. As you all may know, the Cinema is at the centre of a controversy in the city. Both its future and past are uncertain. Cinema Lietuva now sits in a state of suspension, in graffiti covered disrepair and legal limbo. Gediminas and Nomeda Urbonas have been working with others both local and international on the Cinema “case”, turning it into a charged and complex site to negotiate the fraught histories of Soviet Lithuania and its supposed post-Soviet, neo-liberal future. They write: “Since independence in 1991, Lithuania has been caught in an insane period of privatization, property development and demolition. Like a Wild West land-grab or a gold rush, speculators and real estate tycoons have joined forces with corrupt municipal bureaucrats to redevelop the country at a mad pace. Profit has been their only motive. Public space, landmark buildings, cultural life and public opinion have been the principal victims. Their method is simple: tell the population that economic development is good for everyone. Convince them that Capital is King. Remind the public that making Lithuania look like a pale shade of a Western European city is the best way to scrub the Soviet past.” Through a series of workshops, events, objects, exhibitions, texts and legal cases, Pro-testo Laboratorija has turned the cinema into a vehicle to make public the contradictory social forces vying for possession of the built environment. Rather than expediting the process of change, Pro-testo lab slows it down, using the theatre as a device to place contradictory and competitive forces at the heart of the social. The lab exposes the theatre as a contested memorial where the writing of history is not a completed process but one of contestation.

‘Pro-Testo Laboratorija, Lietuva’ Scapegoat: Architecture, Landscape, Political Economy 01: Service (2011). Image courtesy of Gediminas Urbonas and Nomeda Urbonas

‘Pro-Testo Laboratorija, Lietuva’ Scapegoat: Architecture, Landscape, Political Economy 01: Service (2011). Image courtesy of Gediminas Urbonas and Nomeda Urbonas

In The Architecture of the City Aldo Rossi makes two seemingly contradictory claims about the city: he argues, first, that it is the materialization of collective memory, while he also states that “in a certain sense, there is no such thing as buildings that are politically ‘opposed,’ since the ones that are realized are always those of the dominant class.” If this is true, then how can the city express collective history if this will only ever be the history of rulers? Is the city then only ever built by the winners? Pro-testo Laboratorija resolves this contradiction by refusing the resolution of the built environment into a finished history. Instead the city is activated in and through unresolved contestation.

‘Pro-Testo Laboratorija, Lietuva’ Scapegoat: Architecture, Landscape, Political Economy 01: Service (2011). Image courtesy of Gediminas Urbonas and Nomeda Urbonas

‘Pro-Testo Laboratorija, Lietuva’ Scapegoat: Architecture, Landscape, Political Economy 01: Service (2011). Image courtesy of Gediminas Urbonas and Nomeda Urbonas

Scapegoat asked Gediminas: “Has Pro-testo Laboratorija been to disseminate a different public image or reinterpretation of the cinema and its role in culture?” His reply is suggestive of how one can activate the city: “Absolutely. But you see, from a neoliberal perspective any type of project that tries to renegotiate history is not profitable. It puts the dominant scenario into question. Our idea was to think more dialectically and critically about this history and to put into question the nationalist project, neoliberalism, and nostalgia. The past is not resolved, it must be re-negotiated.”

05 Material Inquiry

And so the last practice type that I’m going to talk about is particularly related to the work of Catie Newell form Alibi Studio, who was interviewed by us in the forthcoming issue of materialism for December of this year. The work of renegotiation in the city happens in number of scales. In Detroit it has happened in a particularly strange way as well, given, as I mentioned earlier, the vacancy of 60 percent and also the capacity of completely and totally illegal actions on scales that you may not be familiar with, which is probably for the better.

‘Agitating Architecture’ Scapegoat: Architecture, Landscape, Political Economy 01: Materialism (2011). Image courtesy of Catie Newell of *Alibi Studio Materialism

‘Agitating Architecture’ Scapegoat: Architecture, Landscape, Political Economy 01: Materialism (2011). Image courtesy of Catie Newell of *Alibi Studio Materialism

Trained as an architect, Newell’s recent work in Detroit, Flint, and Chicago deals with a ubiquitous new material that has emerge in the United States, which is empty vacant houses and which she refers to as ‘Once Residences’. For those of you who are really interested in working at the scale of the house without having to build entirely new ones to make into interesting object both architecturally and sculpturally ‒ you should consider going to the Midwest… She explains that because no one is living in them and there is no remaining program, but they maintain the semantic features of the domestic house, there’s actually an incredible capacity for activating these spaces in new ways. So I’m just going to mention two projects. The first one has the title weatherizing, which was the sealing of the house with the removal of its windows and then the re-distribution of those windows by tapered flanged glass tubes to recreate the sense of occupation which is entirely different from what was previously available. The point of this work, according to Alibi studio and Catie in particular, is to try to attenuate and attack the envelope of domesticity as a way of making people really think about what is the occupation of these neglected houses and ask the compelling question of what is really going on in Detroit.

‘Agitating Architecture’ Scapegoat: Architecture, Landscape, Political Economy 01: Materialism (2011). Image courtesy of Catie Newell of *Alibi Studio Materialism

‘Agitating Architecture’ Scapegoat: Architecture, Landscape, Political Economy 01: Materialism (2011). Image courtesy of Catie Newell of *Alibi Studio Materialism

The second piece is called Salvaged Landscape. In Salvaged Landscape there is a burnt house in Detroit (not sure if you know this that people tend to burn their own houses that no one lives in and it’s quite a terrible problem). For this piece she took a part of the burnt house, cut all up and then rebuilt the house out of the burnt scrap, as the way of both dealing with the explosion of these forms of non-occupancy but then also tracing out on the interior with actual gas spill. So when you enter the house the back side is just a series of exploded pieces of charred wood. There’s a way in which the movement from the house traces the actual burnt patterns of the gas leak. One of the reasons that I found this work a really important aspect of Scapegoat, although it is slightly oblique to the other projects, is that she explains it as a process of agitating architecture. And so, as a way of conclusion, this question of not only through MATERIAL INQUIRY but how agitation can happen in relationship with architecture through these different typologies of practice could be something posing two further questions: first, how does this agitation of architecture alleviate the resentments of repetition? As in why we think that repetition is not an entirely negative form. Secondly, how can typologies of practice avoid the pitfalls of illusory progress, promoting instead an aberrant architecture?

The French political activist and theorist of revolution, Louis Auguste Blanqui, who lived in the 19th century, offered a decidedly less optimistic view of repetition and type. With an equally poetic image of the cosmos, Blanqui writes: “What we call ‘progress’ is confined to each particular world, and vanishes with it. Always and everywhere in the terrestrial arena, the same drama, the same setting, on the same narrow stage - a noisy humanity infatuated with its own grandeur, believing itself to be the universe and living in its prison as though in some immense realm, only to founder at an early date along with its globe, which has borne with deepest disdain the burden of human arrogance.”

I thought we would end on a happy conclusion, but then I found out that Walter Benjamin explained why this is a great theory of type. Benjamin in his reading of Blanqui says that “this resignation, this feeling of hopelessness of one of the world’s greatest revolutionists was the result of the century incapable of responding to new technological possibility with the new social order.” The way we might say it today is that it’s easier for us to imagine the end of our planet or our eco-systems than it is to imagine the end of capitalist order. For Blanqui this was very depressing. He views novelty not as a positive attribute of progress but as a sentence of damnation that leads him to hell. This novelty repeats the same over and over and the type here creates the sort of hellish repetition. For Walter Benjamin, to escape this repetition would not be through formal novelty but through practices that that could actually change the social conditions in such a way that could change alongside new technological possibilities.

Convictions could allow us to navigate the present through consideration of type and practice in relation to design commitments or, to end where we started with Walter Benjamin, “Convictions are to the vast apparatus of the social existence what oil is to machines: one does not go up to a turbine and pour machine oil all over it; one applies it a little to hidden spindles and joints that one has to know.” Hopefully some of these spindles and joints are the projects that you’ve got to know in the certain sense and that we’re trying to promote in the magazine. Thank you very much.

Untitled, Scapegoat: Architecture, Landscape, Political Economy 01: Service (2011). Image courtesy of Olia Mishchenko

Untitled, Scapegoat: Architecture, Landscape, Political Economy 01: Service (2011). Image courtesy of Olia Mishchenko

If we want to point to a break in the current form of urbanity and urban practices, it is high time to look at urbanity rather exogenously than endogenously. This means that rather than identifying emergent land uses in the city and groundbreaking social roles correlated to these land uses, we have to ask a question about what is groundbreaking in the ways urbanity sustains and legitimizes emergent social order. As opposed to asking what is topical in urban studies today, we should try to figure out why urban studies became so topical in the last two decades. Instead of figuring out differences in the ways cities are governed and their resources are accessed, we need an understanding of why urbanity is becoming the major locus of innovations in governance and accessibility of resources. At this stage I am tempted to hypothesize that since the end of the WWII ideal type societies were adhering to the model of democratic national policy and technocratic urban policy, while now we are tending to the reverse model where national policy is increasingly technocratic and urban policy is increasingly democratic.

From an exogenous perspective it means that nation-state scale is less and less an appropriate arena for political representation, since national scale politicians are systematically constrained by supra- or extra-national policy and stakeholders. Simultaneously making a city is more and more often considered and lived as a hope for making a new type of citizenship. The examples are participatory city budgets (presumably a symptom of growing hindrances for representation of citizens’ will in national budgets); quantitative increase and qualitative diversification of institutions which take part in urban planning; the fact that urban planning decisions are more and more often becoming the targets for broad political discontent and fierce debates. Thus the most fundamental break that it is timely to point to now is that urban practices obtain a symbolic surplus and a new symbolic dimension in relation to other scale-specific human practices. To put it simply, values of participation are more often projected to the plane of land uses and the built environment. Now the question is how the current matters of a city should change our understanding of participation?

In this context participation should not mean equal participation. The stress is rather that urban land uses and built environments become a more crucial matter for enacting and practicing state sovereignty. Globalization as an increase of foreign investment, intensification of economic international relations and complication of property regimes entails that land and urban milieu in particular become the strategic arenas where different sovereignty regimes are negotiated and crystallized. Currently it is possible to note that the issue is not whether a state is sovereign or not, but what are the various regimes of sovereignty that different states have. From the angle of the state this means that countries compete and position themselves in the global marketplace via their cities and localities, whereas urban projects as both major attractors and filters for people and capital become a crucial part of the sovereignty machinery. From the angle of citizens it means that urbanity is more frequently considered as a common, political issue and as a matter for solidary collective action. That is why today we can talk about popular (as both pop and people’s, not technocratic) urbanism and sometimes about urbanism with a populist flavour. Popularization of urbanism equally means the potentiality for the emergence of a new type of political populism.

Such a role of urbanity means the discovery of a new venue of life via valorization and commodification. If we look at the so-called ‘post-shelter society’ beyond just the financial lens, we notice that human agency is to an increasing extent influenced by various aspects of the urban environment. Urban infrastructures and soft place-making now crucially sustain lifestyle as a source of social distinction and of access to various types of resources. Popular urbanists or urban pioneers, as several studies of gentrification suggest, are the strategic forces in this process. What is significant here is that the popularization of urbanism means the creation of a niche for the new professional identities and professional ethos forming. The examples are specifically urban political activism, journalism for specifically urban life issues, place marketing as opposed to product and territorial marketing, the creation of infinite leisure formats via representations of space, etc. The result is a new combination of being a citizen and being a professional, which is created by the increasing popularization of urbanism. In this respect, one of the key changes this situation brings is a qualitative reconfiguration of the division of labour and hence a reconfiguration of social structure. This innovation is about the massive imitation of the work of, initially technocratic, expert urban planners by a large numbers of citizens.

Given the trend acquires more shades when confronted with the popularity of the term pro-sumption (a combination of production and consumption or professional consumption), characteristic to current job markets. Implicitly it has a geographical dimension too and can be explained as a profound mutation of the work ethos in developed countries due to the internationalization of the division of labour. The pro-sumption phenomenon is usually noticed and interpreted with reference to the realm of new communication technologies, which entail the growing digital mediation of life by user generated content. Here a digital profile as a node of personal data organization and as a new ego framework becomes a decisive infrastructure for the new mode of individuality. In such technological settings individuality is encouraged and mobilized to generate own content by laying claims to common affairs and frequently works as identification with and imitation of existing ethoses – from a celebrity’s ethos to ones of a political activist or an urban planner.

As we know, any technology is successful as long as it hides its bias. Online social networks are appealing because they seemingly provide each actor with the boundaries of his or her individual ego in a fashion of a digital profile. Hidden bias here is that bounding egos this way means also encouraging egos to simulate the agencies, which are initially alien to them. In this sense online social networks are the technologies enabling users to systematically simulate, transgress and blur the boundaries of their social roles and professional statuses. A popularization of urbanism emerges precisely in these settings and it is reinforced by the growing dependence of the urban environment on the mediations of this environment by various individuals and institutions. It immediately exposes the manifold aspects of a city system and overtly presents comfort as the major common affair and as the major grounds for collective action. And since a digital profile structurally encourages individuals to create new content by identifying with the available range of social roles and ethoses, popular urbanism is principally based on the excessive multifunctionality of human action, which stems from the practice of imitation.

In many ways popularization of urbanism and its political consequences constitute the regime of social life, which resembles Plato’s description of theatrocracy. Formally in Plato this concept depicts the destruction of the hierarchy of places and placing, caused by mixing genres through imitation. When we say that urban planning tends to be less technocratic now, it means that its agency can be proliferated. Saying that national policy has turned technocratic means that it is increasingly problematic to share and disperse national rule. Technocratic policy means the prohibition of an excess of rulers’ roles and statuses.

In this light, urbanity as a new venue for common agenda making and as a new matter of what is ruled (city fabric and intra-urban relations) supposes a new mode of participation. The multiplication of digital mediations and of material adjustments of urban systems eliminates the old and produces new frameworks for solidarity or for gluing society together under some cohesive regime. This regime seems to be similar to both the ancient Athenian theatre with the rule of the audience and Plato’s cave with shadows on the wall distorting the true nature of things. It also seems similar to the way the leading communication medium today, online social network, is organized. And within this new digital version of a theatrocratic society a new concept of egalitarianism is being shaped. In contrast to the post-World War II democracies, where egalitarian thinking derived from the citizen’s share in the national economy, today’s egalitarianism seems to derive from the possibility to imitate professional or quasi-professional statuses, in that it is the growing variety of urban situations and dispositions which makes those fabricated statuses relevant and legitimate.

‘The world has entered the urban millennium,’ former UN General Secretary Kofi Annan declared in 2001, referring to the rapid growth of the world’s urban population. Since then, the news has spread among the public and experts alike that from now on, the majority of the world’s people will be city dwellers. And, as you may have noticed, since this statistic was published some years ago, most books and most conferences on global urban phenomena are in fact using this quote to provide the own work with extra emphasis. And so do I this evening…

It is a demographic milestone of truly historic significance, and the statistics are unmistakable; in this millennium urban spaces will become the predominant human habitat on Earth. More people will live in cities, and an ever-growing surface of the planet will be covered by urban spaces causing unprecedented challenges in many urban areas such as shortages of housing and social services, depletion of basic resources, economic woes, environmental problems, and ‒ as a result ‒ social tensions and conflicts.

However, I want to use the quote of the ‘urban millennium’ to make another argument. I want to point out that not all cities are part of this process of vast urban growth. Rather the opposite; the advent of the ‘urban millennium’ is paralleled by a reverse demographic trend: for the first time in history, countries are leaving behind the centuries-long period of population growth and entering a phase of prolonged population reduction.

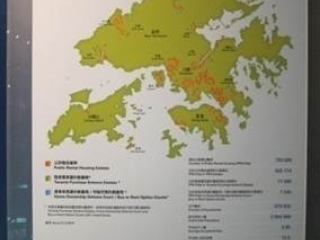

Shrinking countries by 2050; Shrinking Cities / Projektbüro Philipp Oswalt

Shrinking countries by 2050; Shrinking Cities / Projektbüro Philipp Oswalt

This process is without historical precedent too, and will confront the cities that are affected with new challenges as well. These cities, which are losing population against the prevailing trend of urban growth, are confronting us with different kinds of problems and dynamics. These problems might be less urgent than those caused by uncontrolled growth; however, we know even less about them or about possible solutions. For this reason, I want to use this lecture to throw some light on a part of urban history which, until recently, had almost gone ignored, had been forgotten, or considered taboo. A part of urban development, however, that will be of increasing relevance in the 21st century in many regions of the world.

Shrinking cities are by no means a new phenomenon; the loss of population has been as much a part of urban history as growth. The Bible tells us about cities which have been abandoned, destroyed or punished by God. Just think of Sodom and Gomorrah, or of the tower of Babel. And if we investigate other historic sources, we can find numerous other examples. Cities that have been destroyed or fallen victim to fire or natural catastrophes. Cities which have lost their political or economic significance and cities which have been devastated by the Black Death or other epidemics. All these historic cases have one thing in common: they were perceived as catastrophic events of truly existential dimensions, threatening the existence of people, gods and heritage.

Historical examples of shrinking cities; Shrinking Cities / Projektbüro Philipp Oswalt

Historical examples of shrinking cities; Shrinking Cities / Projektbüro Philipp Oswalt

However, since industrialization triggered an accelerated expansion of cities about 200 years ago, we have almost forgotten about shrinking cities. And today, after 200 years of almost continuous urban growth, it is difficult for us to consider shrinking cities as something normal. Instead, we tend to consider it as a deviation from the norm – as a deviation from the normality of continuous growth.

I will take you on a quick time travel – a time travel into the history of shrinking cities. And during this travel I will highlight some of the main reasons for shrinking cities and I will take you to some places which have played a paradigmatic role in the history of shrinking cities. I will focus in particular on the old industrial countries in the 20th century, where urban shrinkage for the first time turned from a timely and geographically limited phenomenon into a widespread and long-term process.

But beside all the details I have some main arguments which I will tell you in advance. A central argument of this lecture is that industrialization did not only cause the ubiquitous economic and demographic growth, as is usually believed. This is just half the truth, because industrialization also enabled developments that worked against the tendencies of growth. I will give you some examples: Cities have suffered from violent destruction made possible by the mechanization and industrialization of war. Cities have experienced waves of out-migration made possible by means of modern transportation techniques. And many cities have experienced unprecedented economic crises, which hit the industrial sector and caused unemployment and deindustrialization. Moreover, the wealth generated through industrialization can be closely linked to demographic processes, such as low birth rates and the aging of populations. Hence, industrialization has not only caused rapid urban growth, at the same time it has contributed to the process of urban shrinking in many ways.

The close relation between shrinking cities and industrialization can accurately be retraced if the historic and geographic developments of growing and shrinking cities are compared. Obviously, the increase and distribution of shrinking cities in the 20th century has followed the same geographic route as that which the growing industrial cities had taken decades before.

The rise of shrinking cities started exactly where the accelerated growth of industrializing cities had its point of departure. The first concentrations of shrinking cities appeared in Central European countries and spread according to the geographic pattern of industrial urbanization. Manchester, known as the first industrial city in the world, was one of the first large cities to experience population loss over the decades to come. Other industrial cities and regions in Europe and the United States followed.

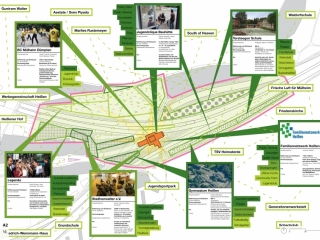

Growing and shrinking cities; Shrinking Cities / Projektbüro Philipp Oswalt

Growing and shrinking cities; Shrinking Cities / Projektbüro Philipp Oswalt

However, as simple as this picture may be, as manifold are the causes and features of shrinking cities. Moreover – and this is another argument I want to make in this lecture – the shrinkage of cities is not just a demographic process that can be quantified by statistics. The shrinkage of cities also means qualitative changes, which cannot be said to follow a basic homogenous pattern. The shrinkage of cities is not only a demographic phenomenon, it rather touches all aspects of urban life and urban development: economic, social as well as cultural aspects. And last but not least, the shrinkage of cities also affects our own profession, because under conditions of urban decline, architecture and urban planning suddenly finds itself confronted with entirely different tasks and possibilities.

This doesn’t mean that we have to forget the methods and instruments we have developed in recent decades. Yet, I am convinced that we need to develop new methods and instruments suitable for the requirements of shrinking cities. We have to invent a new image ‒ a vision of future cities, and we even have to rethink our self-understanding as architects and planners.

All these methods, images and self-perceptions that we are used to, can only be understood in the context of industrial growth. In contrast to older forms of urban planning, which were mainly aimed at military defence, control and representation, the industrial age demanded something else. The industrial age demanded technical solutions to facilitate industrialization and to solve the immense problems it caused. This urgent need gave birth to modern urban planning as we know it today. In short, from an urban planning point of view, urban growth of that time was perceived as a crisis. It was widely identified as the main reason for many of the unbearable conditions in industrial metropolises. Consequently, many planners and theorists of that time period conceived shrinkage as a reasonable strategy to overcome these crises. From this perspective, decentralization, low density, and even shrinkage were not perceived as problems. Rather the opposite, they were widely perceived as desirable alternatives and inspired various urban visions, some of which influenced urban planning for decades to come.

One of the most famous examples is Ebenezer Howard’s concept of the Garden City. It was not just meant to represent a healthy, scenic and semi-rural antipode to the industrial metropolis. Beyond this, Howard wanted his Garden Cities to operate like magnets which – I quote – ‘will produce the effect for which we are all striving ‒ the spontaneous movement of the people from our crowded cities to the bosom of our kindly mother earth.’ And what is less known is that Howard even recommended shrinking London to a mere twenty percent of its population at the time.

Planners in America also developed low-density and decentralization ideas, the most famous of which was Frank Lloyd Wright’s Broadacre City. In his book Disappearing City, he demonized the industrial metropolis as unhealthy, inhuman and corrupt. Against this dystopian background, he promoted the extremely low density of Broadacre City to reverse the failures of urban centralization.

In the course of the 20th century, architects and planners developed numerous other ideas to overcome the problems of fast urbanization. Think of the Russian deurbanists who wanted to rebuild all urban settlements along main traffic infrastructures. Or think of the British architectural group Archigram who invented moving cities. What all these visions ‒ and many others ‒ had in common was that ideas of shrinkage were perceived as controllable developments based on technological progress and opposed to the undesired, disorderly, and failed urbanization of the early industrial metropolises.

Or to put it in simple terms, the technical and economic resources, which had been generated and accumulated within the industrial cities, had to be invested in large-scale utopian projects in order to overcome and dissolve the same industrial cities. In fact, the industrial city with all its problems gave birth to an anti-urban discourse among planners. A discourse which had its point of departure in the 19th century, when socialist reformers and conservative thinkers invented their counter cultural communities, most of which were located outside the city.

Today, large and growing cities are once again the subject of anti-urban discourses. On one hand, there is the discourse on uncontrolled urban growth, especially in the global South. This urban growth is widely perceived as a breeding ground for health problems, social decline, crime and violence. And on the other hand, there is the discourse on sustainable development, which portrays cities – especially the vast and energy thirsty metropolises of the developed world – as major polluters who are damaging and destroying the world climate and natural resources. Again, in both cases size and density and growth of cities are identified as critical parameters.

Economic crises

The early visions of low density and shrinkage never came true. However, at the same time, an increasing number of big cities experienced an unexpected and unplanned loss of population. At the beginning of the 20th century, severe economic crises and supply problems on a national and international level interrupted urban growth in many places. Food supply problems in the wake of the October Revolution – for example – literally drained Russian cities. Millions of urban residents fled to the countryside in order to survive by means of subsistence farming.

Later, the Great Depression in the 1930s also led to temporary urban-rural migration. Urban population loss was less dramatic than in Russia, but nevertheless led to a decline in urban growth rates in all industrialized countries and the shrinking of many cities. Again, people left their cities in favour of rural living conditions or informal settlements where they could self-sufficiently meet their basic needs. This unexpected trend towards interim relocation to rural areas was willingly accepted by many politicians and planners who promoted anti-urban thinking. Modernist and socialist-oriented planners perceived the informal semi-rural settlements as a new symbiosis between city and countryside, whereas conservative planners saw these settlements as a return to an agricultural lifestyle.

In recent years, the world economy again found itself facing major crises. So far, besides numerous projects and construction sites being on hold, the impact of these crises became obvious in the form of the so-called ‘Foreclosure Crises’ in the United States. Suburban areas in which entire neighbourhoods were built on the sandy grounds of uncontrolled speculation have been vacated, literally turning into ghost towns.

Unlike the major economic crisis in the first third of the 20th century, which caused spontaneous out-migration from cities in favour of rural and semi-rural areas, the recent situation seems to be generating a contrary trend. The housing market in the United States and other countries exhibits noticeable signs of the spatial reorganization of suburban areas and a new trend toward more central ones. I will get back to this trend later.

War

Let’s get back to our historic review and focus on another factor which has contributed to the unprecedented increase in shrinking cities in the 20th century: the mechanization and industrialization of warfare. The destructive power of weapons technology developed and mass produced in the previous century, destroyed more lives and cities than ever before.

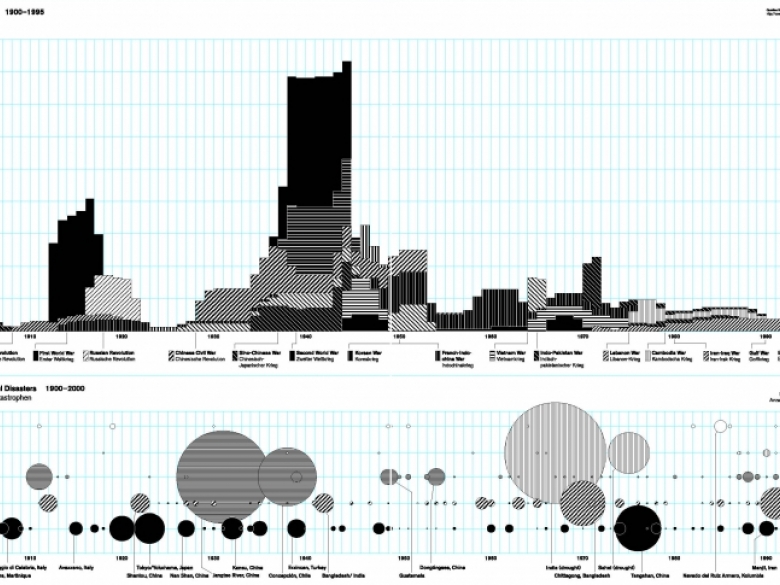

Wars and violent conflicts: Death toll, 1900 – 2000; Shrinking Cities / Projektbüro Philipp Oswalt

Wars and violent conflicts: Death toll, 1900 – 2000; Shrinking Cities / Projektbüro Philipp Oswalt

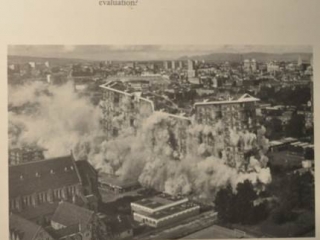

The full potential of modern warfare for destruction and killing was demonstrated in the bombings of cities such as Rotterdam, Coventry, Stalingrad, Hamburg, Tokyo, Dresden, Danzig, and many more in World War II. Here, the targets were not only industrial plants, military facilities, and other neuralgic points of military relevance. Especially German and British Forces targeted civic urban structures in order to demoralize the people and to weaken military and political determination. Finally, the immense destruction of World War II culminated in atomic bombs being dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki. In Hiroshima, one single bomb was enough to destroy two-thirds of the city in one blow ‒ human beings and structures alike.

After World War II, again many concepts for reconstruction were fuelled by the old ideas of decentralization and low density. Many urban planners saw the devastation caused by the war not so much as a loss, but rather as an opportunity to build modern cities and to overcome the insufficient living conditions of pre-war times. In a large number of plans ‒ both realized or not ‒ ideas of low density and a limited number of inhabitants were a central concern.

War and armed conflicts, 1945 – 2001; Shrinking Cities / Projektbüro Philipp Oswalt

War and armed conflicts, 1945 – 2001; Shrinking Cities / Projektbüro Philipp Oswalt

Although threats of mass destruction still exist and have even expanded, new forms of violence and destruction have emerged in the wake of the geopolitical changes caused by the collapse of the Soviet Union and the rise of international terrorism, threatening an increasing number of cities today. Since the rise of modern nation states we were used to wars being fought out outside the city gates, one national army against another. But for some years now, this convention of warfare has been obsolete. Most violent conflicts today are fought out between national armies and informal combatants and at the same time a growing number of these asymmetrical conflicts are taking place in urban environments.

In some cases, such as in the former Yugoslavia, Iraq, or the Caucasus, cities have become the centres of ethnic and nationalist violence. Here, multi-ethnic populations, which had coexisted for decades under the control of authoritarian regimes, suddenly found themselves on the front lines of violent conflicts. Buildings and public spaces were targeted as national and ethnic symbols, and – as I want to argue – also as symbols of urbanity as such.

Suburbanization

Although the mechanization and industrialization of warfare destroyed more lives and cities than ever before, it did not stop the general tendency of urban growth. Most cities affected by military destruction recovered and in most cases even exceeded pre-war population. However, just those regions, which have entered a long period of peace and welfare after World War II – I am talking about the so-called developed countries of the Western World ‒ experienced an unprecedented increase of shrinking cities. Whereas in previous times, urban population losses used to be singular events, restricted to certain places or regions and to certain historic time periods, in the second half of the 20th century, shrinking cities turned into a widespread and long-term phenomenon.

Periods of shrinkage, 1900 – 2000; Shrinking Cities / Projektbüro Philipp Oswalt

Periods of shrinkage, 1900 – 2000; Shrinking Cities / Projektbüro Philipp Oswalt

Right after the War the number of shrinking cities in Western industrial countries rose to approximately one hundred, then grew to over 200 in the 1970s and reached a peak of more than 250 in the 1980s. Not only did the number of shrinking cities rise substantially, according to census data, also the average population losses increased and the average duration of this process became more prolonged.

We can identify two main reasons for this significant and persistent increase of shrinking cities after World War II. Firstly, the once-booming industrial centres suffered an ongoing loss of economic competitiveness, declining labour markets and, consequently, population increase. Secondly, in many regions, the process of urbanization passed into a process of suburbanization, meaning that economic and demographic growth increasingly accumulated outside the urban centres. Residential developments and other urban facilities, such as retail, leisure, and industry, sprawled into the hinterlands and, in many cases, drained the economic, fiscal, and demographic resources of the inner cities.

This process of suburbanization became a central feature of urban development in almost all Western industrialized countries and a major reason for an increase of inner city population losses, especially in the United States. During the 1950s, more than eighty US cities were shrinking, including the twelve largest cities in the country (with the exception of Los Angeles). This rapid transformation was triggered by a combination of different factors. Firstly, the growth of the middle class and their ability to afford cars and single-family homes, the availability of low-interest loans, the extension of highway networks and also the decentralization of employment and consumption facilities.

Combined with a tendency toward ethnic segregation, these factors led to a mass exodus of the mainly white middle classes from city centres, with enormous social, demographic, and economic consequences, especially in the north-eastern United States. Over the years, some major cities like Detroit, Pittsburgh, St Louis or Buffalo lost about half their populations. What used to be bustling city centres were left behind ‒ ruined, half empty and socially deprived. Detroit, for example, shrank from almost two million inhabitants in 1950 to less than one million in the year 2000. The suburban districts around Detroit, however, almost tripled from 1.2 million to more than three million in the same time period.

Population development. Detroit and subburbs, 1900 – 2000; Shrinking Cities / Projektbüro Philipp Oswalt

Population development. Detroit and subburbs, 1900 – 2000; Shrinking Cities / Projektbüro Philipp Oswalt

Deindustrialization

The second reason I mentioned which caused wide spread and long term population losses in industrial countries was and still is the process of deindustrialization. In this case, industrialization did provide the background against which negative demographic trends could unfold. Here, the industry itself was the subject of decline. Especially the old industrial regions that had experienced waves of intense growth in the 19th and early 20th centuries now suffered from the exhaustion of natural resources, outdated means of production, and increasing competition, while new high-technology manufacturing industries and advanced service industries have grown in different regions, competing for skilled labour. Detroit and the so-called Rustbelt is one of these regions; also the British Midlands, where industrialization started is among those regions; as well as the Ruhr and Saar region in Germany, the Po valley in Italy or the Donezk Basin in Ukraine.

Industrial cities and regions; Shrinking Cities / Projektbüro Philipp Oswalt

Industrial cities and regions; Shrinking Cities / Projektbüro Philipp Oswalt

Most of the old industrial cities were not able to offset the loss of economic power resulting from deindustrialization and to compensate the declining industrial sector effectively with new tertiary industries. Manchester, which has suffered from deindustrialization and suburbanization for decades, is one of a handful of industrial cities that has managed to establish a prosperous tertiary sector and to generate new economic and demographic growth.

Manchester brownfields, 2000; Shrinking Cities / Projektbüro Philipp Oswalt

Manchester brownfields, 2000; Shrinking Cities / Projektbüro Philipp Oswalt

Return to the city centres: Urban Renaissance

And there is another phenomenon which had its point of departure in the British Midlands. For the first time, planners and decision makers recognized urban shrinkage as a problem, and not the growth of cities. For the first time, urban planning wanted to work against urban shrinkage. Hence, a new urban policy was developed, which became known under the somewhat glamorous term ‘urban renaissance’. The goal was to refurbish the abandoned city centre and lure young and skilled inhabitants who would otherwise cross the city boundaries to live in the suburbs.

But it was not only planners and politicians who gave birth to the so-called urban renaissance. At the same time young architects and entrepreneurs had discovered abandoned industrial buildings and old working class districts to start their enterprises, to give space to cultural activities, and to live alternative lifestyles. The architectural office Urban Splash was one of these entrepreneurs who started their careers by refurbishing old industrial buildings and turning them into modern lofts and studios – a strategy which is common today, but used to be very progressive at that time. Today, there are no industrial regions which have missed the opportunity to convert old industrial buildings into museums, brain parks and creative clusters.

Regarding the needs of shrinking cities, the advantage of these projects is not so much the architectural quality. It is rather a strategic notion. The notion to invest a minimum of financial resources and a maximum of creative and entrepreneurial resources in order to generate new urban values in a seemingly run down environment. This kind of creative strategic thinking became crucial in other regions with declining urban populations, too.

Post-Socialist conditions

While the number of shrinking cities in Western industrial countries decreased slightly in the 1990s, the dramatic political and economic transformations in the Eastern European countries caused serious urban crises. The collapse of the Soviet Union and the Eastern European planned economies triggered unprecedented demographic developments: within a few years numerous cities fell into a state of political, economic, and demographic instability and experienced rapid population decline.

According to official statistics of the Soviet times, only 27 large cities of all Soviet countries lost population in the 1980s. In the 1990s it was 216 large cities, which means that one out of two cities lost population. Just in Russia, the number of shrinking cities grew from seven to more than ninety. Here, as in other ex-Soviet countries, the collapse of the political system hit the cities so hard that since then, more cities have shrunk than grown, and the urban population of Eastern Europe was in an overall state of decline. After 2000, the downturn came to a halt but shrinking cities were still prevailing and declining faster on average than national populations.

Number of shrinking cities: OECD countries (high income) and post socialist countries; Shrinking Cities / Projektbüro Philipp Oswalt

Number of shrinking cities: OECD countries (high income) and post socialist countries; Shrinking Cities / Projektbüro Philipp Oswalt

The disintegration of the Soviet Union impacted urban populations in many ways, including all the demographic processes I have mentioned: processes of deindustrialization, which used to be obviated by means of the socialist planned economy, suddenly hit industrial regions with full force, especially those where old and formerly protected industries were exposed to the competitive world market, for example the Donezk Basin in Ukraine or the Kusbass in western Siberia. The economic woes and existential fear triggered waves of out-migration and falling birth rates. In addition, the worsening of the quality of life for the majority of the population caused by decaying public healthcare, physical stress, and psychological anxiety, resulted in an alarming decrease in life expectancy. As a result, in 1993 the average lifespan of Russian males was three years shorter than that in the previous year, and reached a low mark of under fifty-nine.

Life expectancy and birth rates in post socialist countries; Shrinking Cities / Projektbüro Philipp Oswalt

Life expectancy and birth rates in post socialist countries; Shrinking Cities / Projektbüro Philipp Oswalt

Eastern Germany is also one of those regions that experienced a severe urban crisis in the 1990s as a result of political and economic change. Rapid deindustrialization, migration to western Germany, and falling birth rates have since caused urban populations throughout eastern Germany to decrease, with some towns having suffered population losses of up to 30% over a 10-year period. But unlike other regions which experienced sudden urban population loss in the wake of the collapse of the Soviet Union the crisis of eastern German cities clashed with the expectations and standards of an advanced capitalist welfare state established in West Germany. It is no accident though that nowhere else did the challenge of shrinking cities gain so much attention and produced so much innovation than in Germany.

Architects, planners, and scholars finally realized the far-reaching implications of the situation and the need to find solutions for a hitherto unknown problem. Architects and planners were being faced with an entirely new task for which nothing in their previous experience had prepared them for: Instead of designing new buildings, old buildings had to be deconstructed, dismantled, or converted; instead of designing new infrastructures, old infrastructures had to be reduced, reorganized, and adapted to less intense use; instead of designing new buildings to host programmes, new programmes had to be invented for existing buildings; and instead of being able to invest the financial surplus of economic prosperity into the urban environment, the losses and disadvantages had to be shaped and controlled in the public interest.

Shrinking cities tomorrow

At the turn of the millennium, inner cities were losing population in unprecedented numbers. Over one in four inner cities with more than 100,000 inhabitants across the world saw their populations fall during the 1990s. Future developments, however, are difficult to project, since urban populations are enmeshed in a multitude of regional, national, and global processes. Yet it is obvious that ongoing urban growth in the southern hemisphere will be increasingly paralleled by the process of urban shrinkage, especially in cities of the developed world. Without trying to make any predictions, I will sketch out some of the most relevant forces that will most likely have a more or less significant impact on future urban population developments.

Shrinking cities, 1950 – 2000; Shrinking Cities / Projektbüro Philipp Oswalt

Shrinking cities, 1950 – 2000; Shrinking Cities / Projektbüro Philipp Oswalt

Demographic change. The most predictable developments we can identify today are demographic in nature and can be projected with a high degree of accuracy on a national scale. In the 21st century, for the first time in history, entire countries will move from a centuries-old phase of population growth to a period of long-term population decline, including the Baltics, Bulgaria, the Czech Republic, Ukraine, and Hungary, as well as Belgium, Spain, and Italy. Urban population growth in the remaining European countries will over the longer term be minute. This demographic turning point will make shrinking cities an increasingly important phenomenon in the decades to come.

The Demographic Impact of Wealth. In many countries, a direct connection can be established between a decline in urban population and general economic prosperity. Because prosperity is a basis for some crucial demographic trends; it allows for mobility and suburbanization and it fosters low birth rates and the aging of populations. The number of shrinking cities has been correspondingly high in affluent countries. Until 1990, three-quarters of all shrinking cities worldwide were in countries categorized as developed countries. If this relationship between wealth and demographic development can be transferred, older industrial regions in developing countries such as India and China may experience similar processes of urban shrinkage in the future.

New Forces of Migration. Besides the overall demographic developments, which can be projected with considerable precision today, many other and sometimes unpredictable factors will have an effect on migration patterns and the demographic development of urban areas. These include rising sea levels, desertification, dwindling freshwater supplies, and the exhaustion of fossil fuels. The 20th century already gave us a foretaste of the destructive impact natural catastrophes may also have in the future. Not long since, scientists and NGOs began warning of a new wave of environmental refugees caused by environmental deterioration. Estimates range from 20 to 25 million today to 150 to 200 million in the future.

Conclusion

As I have tried to demonstrate, the industrial age was not only an age of continuous and exceptionless growth. In many ways, industrialization has also triggered processes of decline. At the same time, the industrial city with all its problems and challenges gave birth to modern urban planning as we know it today. And it gave birth to an anti-urban discourse which has inspired many architects and planners to experiment with ideas of decentralization and even with shrinkage. For a long time, shrinkage was not recognized as a problem, but rather as a concept against the failures of urban density and accelerated growth.

It was not until the end of the previous century and the beginning of the new millennium that planners – especially in England and then in Germany – recognized shrinkage as a challenge. In this context, urban planning found itself confronted with two paradigm shifts. Firstly, the primacy of urban growth, which has defined and legitimized urban planning for more than 100 years, has unexpectedly been complemented by an opposite trend ‒ urban shrinkage. But all of the means and methods in urban planning that had been developed and practiced in order to control urban growth proved to be insufficient. Secondly, while urban shrinkage was long perceived to be a favourable development in order to alleviate the plague of rapid urban growth, it was now perceived as a symptom of crises. In the context of an increasingly globalized economy, where direct competition among cities and regions came to the fore, shrinkage is no longer seen as an advantageous condition.