- INTRODUCTION

- LECTURES

- Miles Glendinning / The Hundred Years War: a ‘Long Century’ of Mass-Housing Campaigns Across the World

- Auguste Van Oppen and Marc Van Asseldonk / Open-Source Urbanism

- Tim Rienets / Less Is More? Urban Design and the Challenge of Shrinking Cities

- Adam Bobbette and Etienne Turpin / Aberrant Architecture: Typologies of Practice

- Matthias Rick / Fleeting Architecture ‒ Raumlabor’s Instant Urbanism

- ESSAYS

- Nerijus Milerius / Breaking Point: from Soviet to Post-Soviet City

- Benjamin Cope / A Reflection on Breaking Points in the Case of The Praga District of Warsaw

- Miodrag Kuč / Berlin. Becoming Normal?

- Mindaugas Pakalnis / Vilnius. The Challenge of Disintegration

- Siarhei Liubimau / Popular Urbanism and the Issue of Egalitarianism

- INTERVIEWS

- No Trust – No City / Matthias Rick Interviewed by Ona Lozuraitytė and Aistė Galaunytė

- The Man, Who Turned the Barbeque into the Center of the World / Benjamin Foerster-Baldenius

- Radicalising the Local / Jeanne Van Heeswijk Interviewed by Kotryna Valiukevičiūtė

- Learning-By-Doing / Laura Panait Interviewed by Arnoldas Stramskas

- Preserving the Generic / Kuba Snopek interviewed by Marija Drėmaitė

- A Permanent Anticipation of Uncertainty / Adam Bobbette interviewed by Arnoldas Stramskas

Jeanne van Heeswijk is a visual artist who facilitates the creation of dynamic and diversified public spaces in order to ‘radicalise the local’. Van Heeswijk embeds herself as an active citizen in communities, often working for years at a time. These long-scale projects, which have occurred in many different countries, transcend the traditional boundaries of art in duration, space and media and questions art’s autonomy by combining performative actions, meetings, discussions, seminars and other forms of organising and pedagogy. Inspired by a particular current event, cultural context or intractable social problem, she dynamically involves neighbours and community members in the planning and realization of a given project. As an ‘urban curator’, van Heeswijk’s work often unravels invisible legislation, governmental codes and social institutions, in order to enable communities to take control over their own futures. Van Heeswijk had her first solo exhibition in 1991 and since then her projects have been exhibited at venues worldwide, including internationally renowned biennials such as Venice, Busan, Taipei, and Shanghai. She regularly lectures on topics such as urban renewal, participation and cultural production.

What does space means to you and how do you approach it?

For me the people’s behaviour in everyday spatial conditions is important. Most predominantly, if I think about space, I think about the local. Not as a fixed community, but as a condition, as a marked territory in which people exercise understanding of or a relation to the space. When I talk about space it is not only about the physical, but also about the emotions and narratives that reside in that space. So beside the local as a physical condition is also relational and emotional.

Has your approach to space changed over the time?

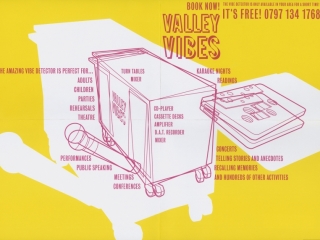

On the one hand my approach didn’t change so much as I always referred to the space of the everyday, the way in which people inhabit space, create a sense of belonging and struggle for daily survival. For example, in the project ‘Valley Vibes. The vibe-detector’, which took place in London in 1998–2003, I worked together with artist and curator Amy Plant and Raoul Bunschoten, who runs Chora, an office for Architecture and Urbanism. The Vibe Detector was designed as a research tool to investigate the different ways in which people connect to their area and to document people's feelings regarding the rapid regeneration process of East London. In workshops we already talked about urban curating in the sense of curare – taking care of the urban condition, which is more than physical streets and houses. What Raoul Bunschoten calls proto-urban conditions are the relations, the memories, the emotions, and the behaviours that reside in the space. On the other hand, now I understand more about the complexity of everyday dynamics than I did 20 years ago when I started to act. I started to understand that this urban condition is what constitutes the local. It is the territory in which people create their sense of belonging and their idea of living together as a group. So through the years I learned more on how these complex dynamics work.

Space is never neutral. Space is already socially constructed before you approach it. What legitimates you to intervene? In what ways does your position as an artist legitimates the interventions that may be more difficult or easier for other actors?

I do think that besides the political, social and economic, the cultural is a very important aspect for citizenship. Today you see that more and more people feel left out from the way their daily environment and future are formed, shaped, governed and financed. So people do not feel they have access to the way in which their daily environment is imagined and narrated. I do think that in order to be a citizen you need to have an understanding of how you could intervene into these processes. In that sense, forms of inhabitations, memory of space or the sense of belonging work through the forms of imagination. So they belong to the field of art and aesthetics. It is a skill set that we, as artists, have and that can help imagine a different relationship, a different understanding of place. This skill set can assist people in taking back the right to the city or take back the possibility of shaping their future. Usually I try to set up what I call ‘a field of interaction’ – a structure based on questions that I derive from the local condition in which I emerge myself, to work with my skill set as an artist. I become a kind of ‘conductor’ channelling energies of space through the artistic body in order to assist images and narratives to take different forms and shapes. I read conducting, as in the Dutch word ‘geleiden’, which means accompanying these energies and flows which reside in the place.

What kind of ethical issues may be at stake in exposing things? How much secret, invisible, non-tourist places are in need of publicity, in need of becoming visible in the touristic ‘creative city’ terms?

I would say, don’t throw away the baby with the bath water! Not all forms of becoming more attractive are bad. But you have to be precise: define what the common good is, and for whom it is good, and you have to make sure that what is then delivered does not exclude people or displace them. So I talk not about making things visible, which is linked to publicity, when you highlight the special points from certain places which then attract either creative industries or tourism, but about making things emergent or, as I would like to call it, radicalising the local. Radicalising in its two connotations: first as making more emergent, the second one that of re-rooting. And this is a process of not only making things emergent, performative, but at the same time making sure that they re-connect and re-root themselves, find grip again in the ground. A lot of people are not helped by gentrification as it often leads to displacement, but they might be in need of connecting already existing qualities and skills in order to strengthen the local. The creative, neoliberal, tourist city prevails a certain narrative of place. So sometimes it is good to show the qualities that already exist in defence against the prevailing narrative.

For example, the project De Verborgen Stad (The Hidden City, 1997) happened in the time when the Middelburg tourist industry was predominantly focused on the city centre, but not on the life of the city itself. The city was playing the beautification card. During the exhibition, twenty-three commentators (artists, activists, writers and thinkers) were invited to comment based on their own backgrounds and disciplines and to propose a spectrum of possible explorations of the back side of the city. Visitors were invited to add information by recording their own findings during their walk through the back of the city, using a disposable camera and a notepad. With the project we said: let’s look at the back alleys, let’s look at the life that is beyond the facade of tourism, what is there? What kind of richness and knowledge resides in that space?

How do you conduct research before starting to act? How do you distinguish the major and other narratives that are interesting to work with? When do you feel it’s enough?

Normally when I start to do my research I go to reside for a while in the location, sponge information and I try not to have an idea. I don't think it is important to stay somewhere for 2 or 3 months but it is important to come back repeatedly – making repetitive insertions, as I call it. During these visits I do what I normally do in my life (go shopping, visit a library, go to a community meeting, see a show, go to the hairdresser). I try to set up a schedule of meeting all kinds of people in the city. Every person I meet I ask him or her to introduce me to another two or three people to talk to. I listen about what it means to live in the city. At some point during these visits a location emerges that is a location of interest. I try to set up a camp, a working space there. After that I create a working structure, I try to find people with whom I can start collaborations. So normally both the point of conflict and the location emerge from the terrain. Next to this I have also my own personal and artistic interests that guide me. So, it is part of my ongoing research into space, into art, into the relation between ethics and aesthetics, and looking how I can assist communities to take matters into their own hands. The series of project I worked at over the last five years were focussed around affordable housing, small scale business and local economies. Now I am looking more at behaviours and relations in space, and the conditions of affect, and ask questions about emotional well-being of space.

Socially engaged practices need time. How do you create conditions for a long time project?

I think it is a problem when people start thinking about socially engaged practices as projects, with beginning and ends. The practice is about creating processes of change, these are durational, often very difficult and they really need time. So you have to find ways in which you can create that time frame and allow it to come into being. I never do more than three projects in a year. And they have to be in different phases as well. If a project is at the height of its development, you cannot do anything else. But if it is at the phase of handing over, I can start research on another one. Creating the financial conditions for a project are also very important for me, I move very carefully in how projects are financed, who is financing and how the financing of construction appears. In a lot of my projects the money is distributed locally. That means that everybody working in the project gets the same equal payment also me. I make sure that I don't work for one specific agenda, even if they have a nice agenda, of NGOs, museums, city councils, housing associations or private owners. I try to create a mix of finances that shows the complexity of the area I am working in. That makes it possible for projects to extend in time, as well. For example, there are over 10 different sources of money in the 2Up2Down project, one being the sale of locally produced bread. (From 2010 van Heeswijk, commissioned by Liverpool Biennial, has been working with people from Anfield and Breckfield in Liverpool to rethink the future of their neighbourhood. K. V.).

What is your approach towards the process and result?

I don't think in process based on art and the result, I think in channelling flows of energy, flows of connectivity, but not like in the process being the art. I do not think that everything can go and in an open-ended process. For me there are forms of flow and continuity in which there are moments where things temporarily gel and some kind of discursive gathering appears. To me these are platforms for collective learning. It is a point of collision, a point of agglutination, where flows of energies materialise for a moment. It is a moment in which the collective knowledge about the site is condensed. That is the moment from which we could collectively learn what we need to do to take responsibilities for a place. These discursive platforms for collective learning are very important so they should be very precise. It can take any form: a discussion, a performance, a song, a book, a film, a game, a shop, or an art piece, but the execution of the format needs to be done well. If you open a café, which makes sloppy coffee, it doesn't work. From this moment you could put things back into the discussion, into distribution again. So I see the multiple results in the process, as a chain of these discursive gatherings.

You work with a lot of people. Besides the artists, architects, writers you invite community members to work together. What are your methods to work together and share the responsibilities?

In my projects I set up teams of what I call experts on location. An expert of location is somebody who has knowledge of place. This could be an inhabitant, someone who lives there because he or she has knowledge of what it means to live there. It could be a shopkeeper, because he or she knows what it means to run a shop in the area. Or it could be kid, who has an understanding of what it means to play in the street. We start working the terrain with a team of people that usually also get paid for their work in the team. It is not about trying to impose an agenda or telling people what they need to do, it is not about delegating responsibility; but it is about finding ways to step up and taking collective responsibility. For my part it is more about letting go than about directing. For that you have to allow difference to be there. So, when people come and say ‘I think I can contribute this’, not only do you have to say ‘yes’, but you have to find ways to assist the process as well. You have to be ready to understand what this person needs to take responsibility. Does he or she need childcare? Does he or she need special training? Do we need extra working session in order to understand things? And, what is also very important is to let people take responsibilities and push in directions that you might not necessarily yourself done. So you have to be able to let things happen.

How do you go with the changes in the direction of the project? Were there cases of disappointment? How do you deal with these?

I try to let projects emerge from the site and I travel along with it. And when I set up a team of experts on location I step into the team as well. So I voice my opinions and my ideas. But the bottom line is that if everybody wants it to be blue, it will be blue. You have to trust people to deal with a situation at hand. Like in the Liverpool 2Up 2Down project the idea was to create a small scale alternative to allow people to take back ownership of their neighbourhood, and to create affordable housing, a community space, and places for small local shops. I never imagined a bakery. But when we set up a camp in a former bakery in a partly boarded up block and started working from there, every day people dropped in asking’ do you sell bread, cake, pies?’ so the group started to feel that it was important to bring the bakery back to life. I wasn’t immediately into it, although I imagined a small local shop as part of the scheme. I thought bakery? I don't even like cake. There were periods in the project when the cake began to overpower the project, everybody was talking only about the baking and it moved away for the very real struggle for affordable housing in the area. So there was a need to bring the balance back. You have to say: a listen person, all this cake is nice, but the bakery is about more, about local produced food, workplaces in the community and having a say in the way in which your area is developed. So it is a field of interaction, a field of different complexities sand desires, and it is about how you balance it.

When performing any actions in space, conflicts often emerge. How do you deal with these conflicts?

Most of the projects are made out of conflict. The fact that they move is because of confrontation. People suggest something, then other people oppose. Disagreements happen constantly as well as conflicts around different understandings of place, different references, narratives, and notions of what is needed for survival. It is in these disagreements that things start moving. Often you see hat city official try to solve conflicts of the local by ‘cleaning’ things out. In my projects conflicts are acted out through the works. For example, with project The Blue House (Ijburg Amsterdam, the Netherlands, 2005–2009), at some point through the whole process of the development of this manmade island in which planners projected that young people in the age group of 14-18 would become a presence as of 2010, more young families moved earlier in the social houses. Everybody in the neighbourhood started to oppose this sudden large group of young boys of predominantly Moroccan background who were hanging in the streets. So, we build them an own meeting space in the house, which was the first time we had a major conflict with the neighbours of the Blue House. Until then they all liked us, because we did activity they thought was nice. But they disliked this action and it started a huge debate about what are desirable and undesirable neighbourhoods. It did not resolve the problem but at least it made the discussion public. The conflict allowed some of the negativities to emerge and created a different form of understanding of the situation.

It seems that you are not searching for a consensus; you are more searching for conflicts. How does one move between the agreement and conflict?

It is a constant struggle. What I try to do with projects, especially when I start to understand more of the dynamics of a place, is setting up a field of interaction which can house the same complexity of different narratives of belonging as resides in the place. If the conflict is around work, I try to form a structure that embodies this. Questions such as should it be a company, a cooperative, an associating or..? become part of the questions that circumscribe the field of interaction. For instance in Afrikaander district (project Freehouse – Market of Tomorrow, Rotterdam, 2008 ‒ ongoing) a networked cooperative structure is around skill based work. This is also the point in which to bring in ‘outside’ expertise as part of the team. You need to bring a lawyer in the team if you want to tackle forms of illegality or legality and have no one on board who understands the matter. The teams of the projects really depend on the complexity. And they also grow or shrink, depending on what is needed. Like with the 2Up 2Down example. At the beginning when we started, we didn't know that a baker would be a very important person to have. A year ago we had to actively look for a baker, somebody with an understanding of baking bread, but also of what it means to train people to become a baker and run a community bakery. Now two bakers are part of the team.

Different specialists work in your teams, including urbanists and architects. What role do you see for different discipline and specialisation in the current times?

I think disciplines are still important to know how to work with discipline skill set and be able to put that discipline in relation to others. I don't believe in crossing disciplines, but I do believe in interdisciplinarity. Giving the complexity of our time we need to work together to get a better understanding of the local condition. And it is hard work to understand how we can work in teams. Autonomy is important, but I believe in what I call relative autonomy or related autonomy – that you use your specific skills and your knowledge in relation to others, so that you are able to assist in the larger complexity.