Aistė Ambrazevičiūtė,

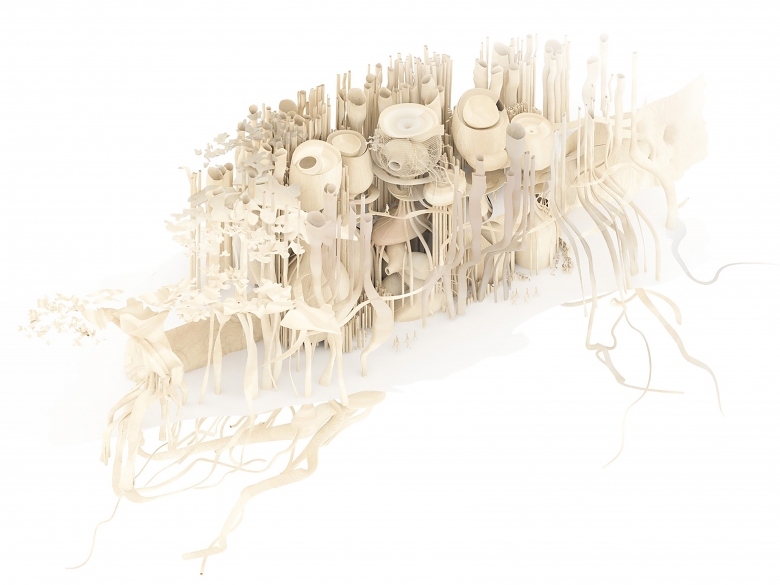

Imaginary Folklore - Recreating the Landscape, Fine Arts Academy Vienna, tutors: Kathrin Aste, Michael Hansmeyer, Wolfgang Tschapeller, 2016.

„The project’s design is based on the complex wood anatomy and material investigation, combining various scales and parts of wood, which enabled to discover new unseen forms out of wood. The aim of the project - to rediscover wooden architecture and its design parameters.“

I am interested in architectural research, creative experiments, pursuit for ideas and consistent project development. In the studies of architecture, as well as its practice, these are the fundamental parts at the core of any good project. Schools of architecture enjoy an exceptional opportunity to engage intellectual thinking, gather together experts in different fields and explore relevant problems, extensively and elaborately go deep into the essence of issues, offer innovative ways for their solution. Critical thinking and spatial analysis not only provide for a solid background for a good study project, but also encourage the community of architects and other professionals to focus on the existing and newly evolving problems, their causes and outcome, as well as potential ways of solution.

Why more research and explorations in architectural studies should be encouraged? First of all, I think, a research in architecture helps to tackle two fundamental questions: (i) scanning architectural space and identifying the emerging problems, still invisible in architectural practice (it contributes to figuring out the potential challenges and threats in the long-term perspective, forming sustainable and coherent principles for the planned modelling of architecture development) and (ii) search for new research methods by experimentation, new architectural principles, innovative technologies and finding ways of their application in architecture practice.

I present this text as a dialogue with different experts in architecture – teachers, school leaders, who share their insights about research and pursuit for ideas in their architectural and educational practices. At the Royal Danish Academy of Fine Arts, Schools of Architecture, Design and Conservation, the Strelka Institute for Media, Architecture and Design in Moscow, and FUTURE+ Aformal Academy of Urbanism, Landscape and Public Art in Shenzhen, China, the interdisciplinary approach, innovations, research and experimentation are inseparable parts of education, in order to educate specialists capable of solving problems or exploring contexts of work and research fields, which today still do not exist, capable of looking for solutions for the most urgent challenges of the day. Therefore, in the text, the representatives of these three educational institutions share their opinions, insights and thoughts on research in educational process.

One of my interlocutors Jason Hilgefort (urbanist, head of the FUTURE+ Aformal Academy for Urbanism, Landscape and Public Art in Shenzhen) notices that correctly formulated question or emphasized key problem often may be even more important than methodical, consecutively performed project and are of more value not only to a student, but also the audience at large. The FUTURE+ Academy under his guidance does not follow the established canons, but rather attempts to foster future leaders by expanding the field of architectural thinking without restricting themselves by the existing specific design and research methodologies.

When asked about creativity in studies, Jason Hilgefort answers: “In many ways what we focus on is creating leaders. We do not believe ‘we know how to do it’ attitude. We encourage our students to try new ways, make mistakes and then we all discuss it together. And this is another key aspect, they are encouraged to debate with each other and the professionals. We think it is good to play and laugh, and experiment. School is a place to try new things, but not a place to be taught a particular methodology.

For us, the studies of spatial practice (architecture, urbanism, landscape, etc.) is not so much focused on only space designing or aesthetics. We try to encourage our students to be more aware of the forces that impact on how spaces are made – political, demographic, economical and other processes. We try to fight the cult of visual material (drawings) that, in our mind, has come to dominate too much and dictate to the spatial practices and sciences. With the use of sections, plans and renders only a very narrow point of view is set. But there are many more manners of expression to explore and create architecture, urbanism or landscaping.

To begin with, we do not teach our students ‘a way’. We certainly encourage them to engage in questioning in a number of ways depending on their skills (for example, with the use of films, interviews or statistical analysis). We also encourage them to test the ways, which they and often we are not used to. We strongly push them to both think analytically and abstractly creative at the same time. For the sake of something new, still undiscovered… We also encourage the sharing within a group. The process is not ‘yours’ and ‘mine’. We are exploring and collaborating to learn, but never competing for better grades. We see it facilitating them to find their own creative path, their own methods, rather than dictating a dogma.

For us, it is important to see all the systems and processes that often architects just take for granted. To understand the process first. Who is doing the commissioning? Where is the money for the project coming from? What is the goal of the developer with this project? How does energy get to the site? Where does the water come from and go? How will management of the site work after it is built? What other forces, influences can we use to impact, affect the project? What else could or should be there? If not now – even in a few years? The notion that we strive to have is putting a priority on, but not hierarchy. Thus, this way of learning goes in all directions.

Architecture, urbanism, landscaping, etc. – all these spatial practices cover many aspects. Some students want to detail windows, but many don’t. Some are interested in dealing with political motivations behind commissions in their future careers, some are less so. We attempt to keep the program broad, with “deep valleys”, so that each student could find his/ her own activity map, just in opposite to the broadly used standardized typologies of graduates.”

Whereas Kuba Snopek (urbanist and researcher, tutor at the Strelka Institute of Media, Architecture and Design in Moscow) emphasizes the importance of correctly formulated task for the study work aimed at the grounded result:

“I believe in the importance of two components that architecture students don’t give that much attention to: the brief and research. First of all, the brief must be formulated correctly, approved by and fully clear to all groups of the common process. Secondly, in the research, the essence often is to understand properly the function of the building, or how it should perform. I always try to get to the core of it – what is a theatre? What is a dwelling? What does it mean to read a book or to pray? For me, a research definitely does not start with the site, but with the core function the building is about to perform.

The process of research (that actually leads to establishing the core idea of the building) is always very similar by its structure, but differs in thousands of details in every given case. It consists of the following parts: (a) data collection and a quick research of all related fields; (b) recognition of patterns in the collected data; (c) naming the patterns; (d) “ideation” – application process of the recognised patterns in a specific case.

The essence is simple: answering one underlying question – ‘WHY?’ In every project done at Strelka and by myself, at every single stage of it, the development motives must be clearly set. To put it simple, every time you draw a line, you should understand WHY you are drawing it. Architecture always needs to have a strong rationale.”

Arne Cermak Nielsen (Danish architect, partner at BCVA and teacher at Copenhagen Royal Academy of Fine Arts, School of Architecture) adds that it is also important to find a potential of a place, its added value, which is sought after by himself in his practice and his students’ works. He says:

“Study programmes, I believe, should always have some kind of social starting point, be socially responsible. Any current issue, crisis or urgent need can be addressed through the prism of architecture or urban planning. While designing in a specific territory, the livability of the environment could be increased, for example, by creating a public space or unique building offering something in return to the space it occupies. By identifying such livability aspects, projects of the students may gain greater value. Many global, national and local issues can be addressed fully or partly by the means of architecture and urban planning. I therefor recommend the students to follow the news, debate and statistics in order to locate the scope of their projects.

Often it is hard to persuade private clients to seek for social responsibility on broader scale, so it's essential to tell them what their benefits are. Some cities in Denmark, however, are able to formulate their consecutive urban architecture policies and action plans, which we can use as guidelines together with the clients. It certainly helps the dialogue with the authorities if the client and adviser understands these soft values as well - and not just the legal restrictions of density, program and building heights.

Similar approach is also declared by Slavis Lew Poczebutas (partner of MEKADO architectural studio, Berlin, former project director at OMA, guest teacher at different universities), has been a guest professor at VGTU over the last years, working with local students in the format of short and intensive design and implementation workshops. When he started to teach at the architecture faculty, the format of workshops as means of experimenting intensively and freely on certain topics had not been established yet, but explored and tested successfully since.

He is encouraging the faculty to continue to open up the dialogue and format of teaching to explore and debate on pressing challenges of our contemporary and increasingly complex life which evolves and changes around us. Architecture schools need new methods of architectural and urban thinking and organization to develop solutions for a progressive urban future. The architectural education has to encourage students to be curious, asking questions, be critical and to develop their own passion and creativity for topics on and beyond architecture that today have an increasing influence on the urban world and its inhabitants and users.

So, the experts from different places of the world I have talked to say different things about creativity, they apply different methods and develop different projects, but they have unanimously stated the importance of research and experiment in the process of finding any given project’s essence, nature and problems. In addition to this, all my interlocutors have emphasized the need for intensive work not only among students, but also teachers, which is actually happening in their alma maters – each lecture requires intensive preparation work, work during it and a lot of discussion and/or reflection after it. Teachers compete thus attempting to maintain high quality of studies in different groups or departments.

To solve the issues (or rather challenges) that recently appear in Lithuania requiring complex and uneasy solutions, just the good practice examples from abroad are no longer enough, they require innovative and unique ways of solution, as well as complex, strategic and creative exploration path. For meeting such challenges, cities also need entire teams of experts, including not only urban planners, architects, constructors, but also politicians, designers and even urban activists.

Today, an architect, urban planner or landscape designer has to be capable of not only solving the emerging urban problems on the professional level, but also finding, identifying them. Teaching how to find out, understand and evaluate complex problems and challenges, discuss and hear other opinions, find common vectors for activities has to be the prerogative of schools of architecture. The schools mentioned in the text still learn themselves how to discover, understand and perceive, and they help different organizations and institutions in doing this. By gathering experience through study researches, the STRELKA Institute works in collaboration with different institutions in organizing competitions and other urban processes important for the city of Moscow. Teachers and students of the FUTURE+ Academy give lectures and creative workshops to pre-schoolers, elderly people and local communities. The distinctive feature of work of Copenhagen Royal Academy is presentation of its students’ graduation works to experts of different areas, town residents and even tourists at large exposition spaces.

Without any doubt, the primary mission of any university is training a good professional in a certain area, but a university has also to be the place, where important issues can and, I believe, should be analysed, causes and ways of solution of different processes looked for, strategies developed for possible city scenarios, discussions among experts held and society at large enlightened. The schools of architecture discussed in this article are good examples of how architectural education trespasses the boundaries of just teaching technical subjects. All the interlocutors have emphasized the importance of fostering a self-confident personality able to think, gather and analyse critically the information, create innovations and trespass the boundaries of sticking to standardized and established methods in preparation of any project – of a house, city, street, park or even a computer software.

Ignas Uogintas is an architect and partner of DO ARCHITECTS office since 2015. With the DO ARCHITECTS team, he works on such projects as the territory development of Svencelė, Ogmios Miestas in Vilnius, Misionierių Namai, the apartment block quarter in Vilnius. Before joining the DO ARCHITECTS team, Ignas worked with different architecture offices in Lithuania, Spain, Poland, Netherlands and Denmark gaining different professional experience.

Ignas Uogintas graduated from Copenhagen Royal Academy of Fine Arts, School of Architecture, studied at the Academy of Architecture in Amsterdam and Vilnius Gediminas Technical University, the Faculty of Architecture. In his graduation work for the Master degree, Ignas analysed the history, problems and development possibilities of Pašilaičiai residential district in Vilnius, from small interventions to the entire regeneration of the district. Ignas Uogintas’ graduation paper for the Bachelor degree has won an award of the best study project in Lithuania.

The major part of his projects, researches and studies has been related to analysis of architectural and urban structures in cities and their development in problematic territories focusing on broader spatial, sociocultural, economic and other contexts.

Aistė Ambrazevičiūtė, Imaginary Folklore - Recreating the Landscape, Fine Arts Academy Vienna, tutors: Kathrin Aste, Michael Hansmeyer, Wolfgang Tschapeller, 2016.

„Projekto koncepcija pagrįsta sudėtinga medienos anatomija bei mikro analize, derinant įvairius mąstelius ir medžio dalis. Tai leido pamatyti naujas nematytas medžio formas. Projekto tikslas - iš naujo atrasti medinę architektūrą ir dizaino parametrus.“

Mane domina architektūrinis tyrimas, kūrybinis eksperimentas, idėjos ieškojimas ir nuoseklus projekto vystymas. Tiek architektūros studijose, tiek praktikoje tai yra fundamentalios dalys, dedančios pagrindą geram projektui. Aukštosios architektūros mokyklos turi išskirtinę galimybę „įdarbinti“ intelektualų protą, burti skirtingų sričių specialistus ir tyrinėti aktualias problemas, plačiai ir tuo pačiu kruopščiai gilintis į problemų esmę, siūlyti inovatyvius sprendimo būdus. Kritinis mąstymas, vietos analizė ne tik sukuria tvirtą pagrindą geram studijų projektui, bet ir skatina platesnę architektų ir kitų profesionalų bendruomenę kreipti dėmesį į esamas ir naujai kylančias problemas, jų priežastis ir pasekmes, potencialius sprendimo būdus.

Kodėl reikia daugiau tyrimų ir ieškojimų architektūros studijose? Visų pirma, manau, kad tyrimas architektūroje padeda atsakyti į du svarbius klausimus: pirma – skenuoti architektūros erdvę ir identifikuoti kylančias problemas, su kuriomis architektūros praktikoje dar nesusidurta (tai padeda nuspėti potencialius iššūkius ir pavojus ilgoje perspektyvoje, sugalvoti tvarius, nuoseklius principus planingai modeliuoti architektūros raidą) ir antra – ieškoti naujų tyrimo būdų, eksperimentų formomis, funkcijomis, architektūriniais principais, naujomis technologijomis bei jų pritaikymo būdais architektūros praktikoje.

Šį tekstą rašau kaip dialogą, jame kalbindamas skirtingus architektūros ekspertus – dėstytojus ir mokyklų vadovus, kurie dalinasi savo pastebėjimais apie tyrimą ir idėjos ieškojimą savo architektūros projektuose ir savo studentų studijų darbuose. Kopenhagos Karališkojoje menų akademijoje, architektūros fakultete (The Royal Danish Academy of Fine Arts

Schools of Architecture, Design and Conservation), ar STRELKA medijos, dizaino ir architektūros institute Maskvoje (Strelka Institute for Media, Architecture and Design), ar Šendženo urbanistikos, kraštovaizdžio ir vizualinių menų akademijoje ( FUTURE+ Aformal Academy of Urbanism, Landscape and Public Art) – tarpdiscipliniškumas, inovacijos, tyrimas ir eksperimentavimas yra neatsiejama edukacijos dalis, siekiant išugdyti specialistus, kurie gebėtų spręsti problemas, kurių dar šiandien gal net negalime įsivaizduoti ar kurių darbo ir tyrimų lauko kontekstai dar net neegzistuoja; gebėtų ieškoti aktualiausių šių dienų iššūkių sprendimų. Todėl šių trijų institucijų atstovai (ir aš) tekste pateikia savo nuomonę, įžvalgas ir pamąstymus apie tyrimą edukacijoje.

Vienas iš mano pašnekovų, Jasonas Hilgefortas (urbanistas, Šendženo „FUTURE+“ urbanistikos, kraštovaizdžio ir architektūros akademijos direktorius) pastebi, kad dažnai teisingai suformuluotas klausimas ir išryškinta esminė problema gali būti net svarbesnė, nei metodiškai nuosekliai atliktas projektas ir yra vertingesnis tiek studentui, tiek ir platesnei auditorijai. Jo vadovaujama „FUTURE+“ akademija nepaiso nusistovėjusių kanonų – jie siekia auginti ateities lyderius plėsdami architektūrinio mąstymo lauką, neapsiribodami konkrečiomis egzistuojančiomis projektavimo ir tyrimo metodologijomis.

Paklaustas apie kūrybiškumą studijose, Jasonas Hilgefortas atsako: „Mūsų tikslas – kurti lyderius. Mes netikime nuostata: „mes žinome, kaip tai padaryti“. Skatiname naudoti naujus, principus ir būdus, eksperimentuoti ir nebijoti klysti, kiekviename žingsnyje diskutuoti ir analizuoti kartu su komanda. Studentai yra skatinami diskutuoti ne tik tarpusavyje, bet taip pat ir su profesionalais. Mes manome, kad būtina žaisti, išdykauti ir eksperimentuoti. Mokykla – tai vieta išbandyti naujus dalykus, o ne išmokyti konkrečios proceso metodologijos. Mums erdvės mokslų studijos (architektūra, urbanistika, landšaftas ir kt.) nėra paremtos vien erdvių projektavimu ir estetika. Mes siekiame skatinti būti sąmoningiems ir suvokti politinius, demografinius, ekonominius ir kitus procesus, kurie daro įtaką erdvių kūrimui. Stengiamės kovoti su vizualinės medžiagos kultu, kuris, mūsų nuomone, šiandien pasaulyje per daug dominuojantis ir diktuoja erdvinių praktikų ir mokslų veiklą. Naudojant pjūvius, planus, vizualizacijas kuriamas tik labai siauras požiūrio taškas. Bet yra daug daugiau priemonių, kuriomis galima tyrinėti ir išreikšti architektūrą, urbanistiką ar landšaftą.

Visų pirma, mes nemokome studentų „amato kelio“. Žinoma, skatiname studentą įsigilinti į klausimo esmę įvairiais aspektais, priklausomai nuo jo įgūdžių (pavyzdžiui, per kinematografijos, interviu ar statistinės analizės prizmę). Taip pat skatiname išbandyti skirtingus kelius, kurių jie, o dažnai ir mes, dar nesame pramynę. Mes taip pat stipriai stumiame mąstyti analitiškai ir abstrakčiai kūrybiškai vienu metu. Vardan kažko nauja, neatrasta... Taip pat mes skatiname dalintis komandoje. Procesas nėra „mano“ ar „tavo“. Ieškome ir dirbame kartu, kad atrastume, o ne varžytumėmės dėl geresnių rezultatų. Taip norime palengvinti atrasti savo ieškojimų ir kūrybos kelią, savo metodus, o ne diktuoti dogmą. Mums labai svarbus visas procesas ir sistemos, susijusios su projekto vystymu, kurį dažnai architektai nuvertina. Pirma – svarbu suprasti procesą: „kas užsako projektą?“; „iš kur atkeliauja pinigai projektui?“; „koks yra vystytojo tikslas šiuo projektu?“; „kaip atkeliauja reikalinga energija?“; „kaip projektas bus vystomas po statybų pabaigos?“; „kokios kitos jėgos ar įtakos gali daryti poveikį projekto vystymuisi?“; „ko projektas nėra numatęs ir kas galėtų atsirasti ateinančiais metais?“. Tai darome tam, kad sudėliotume proceso prioritetus, bet ne hierarchiją. Šis mokymo kelias veda labai įvairiomis kryptimis.

Architektūra, urbanistika, landšaftas ir kita – visos šios erdvinės praktikos apima labai daug aspektų. Kai kurie studentai nori gilintis į architektūrines detales, kaip namo lango jungtys, kiti apie tai negalvoja. Kai kurie yra susidomėję politiniais aspektais, turėsiančiais įtakos jų ateities karjerai, kiti apie tai negalvoja. Mes stengiamės turėti plačią studijų programą, su „giliais slėniais“, kad kiekvienas studentas galėtų turėti savo paties sudėliotą veiklų žemėlapį, visišką priešpriešą plačiai naudojamam standartiniam studijų projekto rengimui.“

Tuo tarpu Kuba Snopek'as (urbanistas ir architektūros tyrėjas, „STRELKA“ Medijos, dizaino ir architektūros instituto Maskvoje dėstytojas) pabrėžia teisingai suformuluotos užduoties studijų darbams svarbą siekiant argumentuoto rezultato:

„Manau, kad architektūros studentai dažnai nuvertina dvi dalis: užduotį ir tyrimą. Pirma, užduotis turi būti teisingai suformuluota, suderinta, ir iki galo aiški visoms bendro proceso grupėms. Antra – tyrimas, kurio esmė dažniausiai yra suprasti pastato funkciją – kaip jis turėtų veikti. Visada stengiuosi atrasti esmę: „kas yra teatras?“; „kas yra gyvenamasis namas?“; „ką reiškia skaityti ar melstis?“. Manau, mano projektuose tyrimas niekada neprasideda nuo vietos, bet nuo esminės statinio funkcijos, aplink kurią sukasi visas pastato gyvavimo procesas.

Tyrimo procesas (kuris veda pagrindinės projekto vystymo idėjos link) yra visada panašus savo struktūra, bet varijuoja tūkstančiu detalių kiekvienu konkrečiu atveju. Pagrindinės sudedamosios dalys yra šios: a) tyrimo duomenų bazės kaupimas ir trumpas visų dalių tyrimas; b) dėsningumų sukauptuose duomenyse atradimas ir išgryninimas; c) dėsningumų įvardinimas; d) „idėjinimas“ - atrastų dėsningumų pritaikymas konkrečiam atvejui ateityje.

Viso to esmė paprasta – atsakyti į vieną fundamentalų klausimą – „KODĖL?“. Kiekviename projekte, atliktame „Strelka“ institute ar mano asmeniškai, kiekvieno etapo metu turi būti aiškūs vystymo motyvai. Paprastai tariant, kaskart brėžiant liniją turi suprasti KODĖL tu ją brėži. Architektūra turi turėti stiprų racionalų pagrindą.“

Arnas Cermakas Nielsenas (danų architektas, BCVA architektų kontoros partneris, taip pat dėstytojas Kopenhagos Karališkojoje architektūros akademijoje) pridurtų, kad svarbu atrasti vietos potencialą, jos pridėtinę vertę, to jis pats savo praktikoje ir savo studentų darbuose ieško:

„Studijų programos, manau, turi visada turėti socialinį atspirties tašką, būti socialiai atsakingos. Aktuali visuomenei problema, krizė ar kažko poreikis gali būti tiriamas per architektūros ar urbanistikos prizmę. Projektuojant konkrečioje teritorijoje, galima pakelti aplinkos gyvybingumą, pavyzdžiui, sukuriant viešą erdvę ar unikalų statinį, kurie galėtų pasiūlyti grąžą aplinkai. Atradus tokius gyvybingumo aspektus pats studento darbas gali turėti didesnę vertę. Tiesa sakant, manau, svarbu sekti tiek globalius, nacionalinius ar lokalius įvykius ir, atsiradus galimybei, susiklosčiusią problemą spręsti architektūrinėmis ar urbanistinėmis priemonėmis. Todėl savo studentams rekomenduoju sekti naujienas, debatus ar net tam tikrą statistiką, kad būtų lengviau identifikuoti jų projektų apimtį.

Atrasti ir įtikinti privačius užsakovus siekti socialinio atsakingumo platesniu masteliu dažnai būna sunku, jei tai neatneša konkrečios naudos jiems asmeniškai. Tačiau kai kurie Danijos miestai geba nuosekliai kurti miestų architektūros politiką ir veiksmų planus, kuriuos seka ir teritorijų vystytojai. Vystytojų ir projektuotojų „minkštų teritorijos vertybių“ supratimas palengvina dialogą su valdžios institucijomis, kurios yra daug platesnės, negu vien teritorijos tankumas, programa ir aukščiai.“

Panašiai mąsto ir Slavis Lewas Poczebutas (Berlyne įsikūrusios „Mekado“ architektūros studijos partneris, buvęs OMA studijos projektų vadovas, taip pat dėstytojas svečio teisėmis įvairiuose universitetuose), ieškantis būdų naujai pažvelgti į pačią architektūros studijų projektavimo programą Lietuvoje, VGTU Architektūros fakultete, eksperimentuojant su formatu. Slavis VGTU Architektūros fakultete pristatė intensyvias kelių savaičių komandines kūrybines dirbtuves grupiniams projektams realizuoti. Jų rezultatas – kelios erdvinės instaliacijos ir paviljonai, sukurti pačių studentų. Lietuvos studentams neįprastas projekto formatas, komandinis darbas, naujos temos sukuria prielaidas pažvelgti į projektavimo procesą nutolstant nuo standartinio studijų projekto darymo ir individualiai ar komandoje apmąstyti daug įvairiapusių, nenuspėjamų klausimų.

Slavis Lewas Poczebutas pastebi, kad „architektūros mokyklos turi pastoviai ieškoti naujų architektūros ir urbanistikos mąstymo ir vystymo metodų, kad neatsiliktų nuo bendrų miestų kaitos tendencijų, augant urbanizuotam pasauliui ir didėjančiam inovacijų poreikiui. Architektūros mokykloms reikia naujų metodų architektūriniam ir urbanistiniam mastymui ir naujų procesų vystymo progresyviems ateities miestų sprendimams. Architektūros edukacija privalo skatinti studentus domėtis, klausti, būti kritiškiems ir savikritiškiems, vystyti savo, kaip profesionalo, aistrą ir kūrybiškumą architektūros temoje ir už jos ribų.

Mano kalbinti ekspertai iš skirtingų pasaulio vietų skirtingai kalba apie kūrybingumą, jų metodai ir projektai skiriasi, bet jie visi vieningai pabrėžia tyrimo ir eksperimentavimo svarbą siekiant atrasti projekto esmę, prigimtį ir problematiką. Taip pat, visi pašnekovai pabrėžia, kad šiose architektūros mokyklose intensyvus darbas turi vykti ir vyksta ne vien tarp studentų, tačiau ir tarp dėstytojų – kiekviena paskaita reikalauja intensyvaus darbo paskaitai ruošiantis, jos metu, diskutuojant ar apmąstant po paskaitos. Dėstytojai konkuruoja ir taip stengiasi išlaikyti aukštą studijų kartelę tarp skirtingų grupių ar katedrų.

Lietuvoje pastaraisiais metais kylantiems iššūkiams, reikalaujantiems kompleksinių ir nelengvų sprendinių, nebepakanka gerųjų praktikų pavyzdžio iš svetur, jie prašosi inovatyvių ir unikalių sprendimo būdų bei kompleksinio, strateginio ir kūrybinio ieškojimų kelio. Tokiems iššūkiams spręsti pavienių specialistų nebepakanka, drauge į procesus turi įsitraukti nuo urbanistų, architektų, statytojų iki politikų, interjero dizainerių ar net miesto erdvių entuziastų.

Šiandiena praktikoje architektas, urbanistas ar landšafto specialistas turi gebėti ne vien profesionaliai spręsti iškilusias miestų problemas, bet ir jas atrasti, identifikuoti. Mokytis atrasti, suprasti ir įvertinti kompleksines problemas ir iššūkius, mokytis diskutuoti ir išgirsti, atrasti bendrus veiklos vektorius, galime architektūros aukštosiose mokyklose. Tekste minėtos architektūros mokyklos pačios mokosi ir padeda skirtingoms organizacijoms ir institucijoms atrasti, suprasti ir pažinti. STRELKA institutas, kaupdamas patirtį per studijinius tyrimus, glaužiai dirba su skirtingomis institucijomis organizuojant Maskvai svarbius konkursus ir kitus urbanistinius procesus, FUTURE+ akademijoje dėstytojai ir studentai dėsto paskaitas ir daro „workšopus“ su ikimokyklinio amžiaus vaikais ir seneliais, vietinėmis bendruomenėmis, Kopenhagos Karališkoji akademija pristato savo platų bigiamųjų darbų spektrą įvairių sričių specialistams, miestėčiams ar net turistams didelėse ekspozicijų erdvėse.

Žinoma, pirminė universitetų misija – išugdyti savo srities specialistą, tačiau universitetas – taip pat vieta, kurioje gali ir, manau, turi būti nagrinėjamos svarbios problemos, ieškoma procesų priežasčių ir sprendimo būdų, kuriamos strategijos galimiems miestų scenarijams, vyktų diskusijos tarp specialistų, šviečiama visuomenė. Aptartose architektūros mokyklose architekto edukacija išeina iš techninių dalykų mokymo rėmų. Visi pašnekovai pabrėžia, kad svarbu ugdyti mąstančią, savimi pasitikinčią, mokančią rinkti informaciją ir ją kritiškai vertinti asmenybę, gebančią analizuoti ir kurti inovacijas, neapsiribojant standartiniais, nusistovėjusiais metodais, kad ir kas tai bebūtų – namas, miestas, gatvė, parkas, ar net kompiuterinė programa.

Ignas Uogintas yra architektas ir DO ARCHITECTS biuro partneris nuo 2015 metų. Su DO ARCHITECTS komanda dirba prie tokių projektų, kaip Svencelės teritorijos plėtra, „Ogmios miesto“ Vilniuje teritorijos plėtra, daugiabučių kvartalo Vilniuje „Misionierių Namai“. Iki prisijungiant prie DO ARCHITECTS komandos Ignas savo profesine patirti rinko architektūros ofisuose Lietuvoje, Ispanijoje, Lenkijoje, Olandijoje, Danijoje.

Baigė architektūros studijas Karališkojoj Kopenhagos Architektūros Akademijoje, prieš tai mokėsi Amsterdamo Architektūros Akademijoje ir Vilniaus Technikos Universitete, Architektūros fakultete. Magistratūros baigiamasis darbas plačiai nagrinėja Vilniaus Pašilaičių mikrorajono istoriją, problemas ir vystymo galimybes nuo mažų intervencijų iki rajono regeneracijos. Igno Uoginto bakalauro baigiamasis darbas buvo apdovanotas geriausiu studijų projektu Lietuvoje.

Su architektūriniais ofisais yra daręs projektus ir laimėjęs ne viena architektūrini konkursą įvairiose šalyse. Tarp svarbiausių tarptautinių laimėjimų - pirma vieta Helsinkio Pietinio Uosto teritorijos urbanistiniame konkurse 2011 metais, prie kurio dirbo su „MAXWAN“ architektų komanda iš Roterdamo.

Didžioji dalis projektų, tyrimų ir studijų buvo susiję su miestų architektūrinių ir urbanistinių struktūrų analize ir kūrimu problematinėse teritorijose atkreipiant dėmėsi į platų erdvinį, sociokultūrinį, ekonominį ir kt. kontekstą.

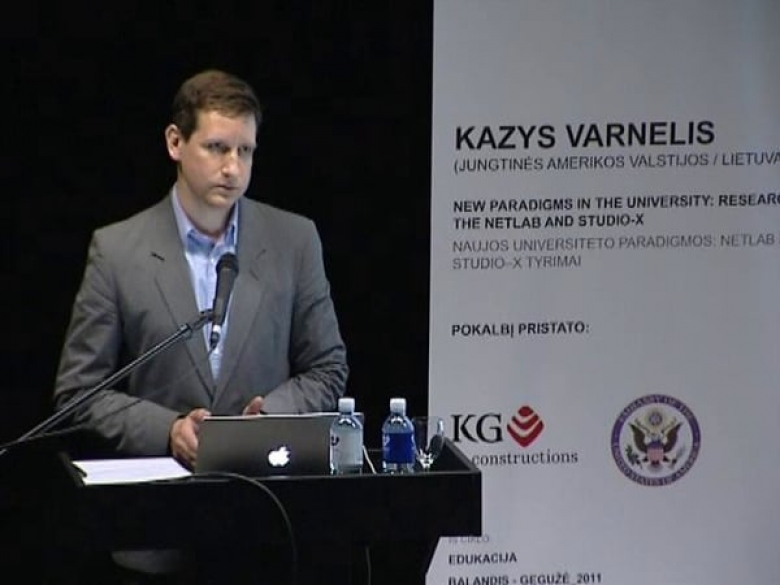

Today I am going to talk about education in architecture and, in particular, the Studio-X initiative at the Columbia Graduate School of Architecture, Planning and Preservation (GSAPP). Created by Dean Mark Wigley, this initiative serves as a model for both globalization in education as well as the relationship between architecture and research.

Wigley calls for educating “the expanded architect,” challenging students to think outside of the bounds of what conventionally is possible in architecture, to use the radical thinking developed in architectural education in other spheres, even those quite removed from the built domain. In the second half of this talk I will discuss an example of how the expanded architect might function in terms of my own practice, the Network Architecture Lab. The global context is key for Wigley, who argues that “if we do not think about the future in and with all the transformative regions of the world, then we are not thinking about the future.” For Wigley, the huge geopolitical changes going on worldwide—globalization, the rise of China, the end of the Soviet Union, the development of Brazil, India, and so on—are not just political and economic transformations but also produce changes in both thought and architecture. In American universities, there have been fundamental changes as well. In the 1960s, virtually all the faculty and students in Columbia’s architecture program were white American males. Now American students and faculty are much more diverse as students from across the world come to study here. Consequently, addressing global changes has become a matter of greater urgency and Wigley proposes that instead of serving as a colonial enterprise with satellite campuses worldwide, the university can expand beyond its local condition to become a platform for establishing systems of cooperation.

Studio-X

Wigley’s approach to this is the development of the Studio-X program (“X” standing for experimental). The Studio-X global network is composed of nodes located in megacities, with facilities in New York, Beijing, Tokyo, Amman, Mumbai, Rio de Janeiro, Moscow, and Johannesburg. Each individual node is not a traditional classroom or studio venue, but may rather be ascribed to a global interface, a gallery, a library, a lecture space, a meeting room, an office, or a coffee bar. In various ways these elements combine to form each Studio-X node which in turn becomes a place for developing creative approaches to solve the most pressing problems of urban transformation. In theory, at least, each of the nodes becomes equally important and they all become centers of activity. Unlike say, New York University’s Global Programs, it is not meant to export leadership, education and research around the globe or to provide a place for study-abroad programs, but rather to understand that as much as Columbia has a great deal to offer, it also has a great deal to learn. The university advances as a learning institution as it expands into this network.

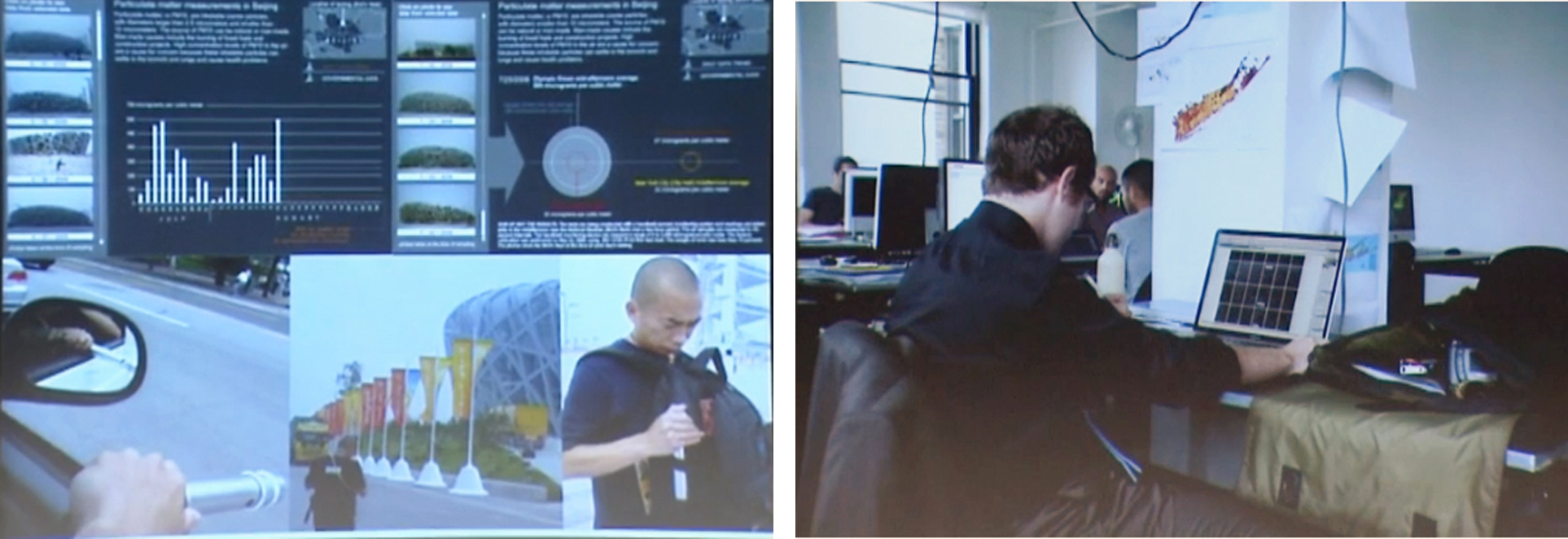

These images are of the global prototype Studio-X in the SoHo district of New York. It is located in 180 Varick Street, a building that is itself a kind of incubator for some of the most advanced architectural thought in the country—2 X 4 Design, Michael Sorkin, OMA, Toshiko Mori and other practices are located in the building. Studio-X is rather inconvenient to get to from the university’s campus, being located forty minutes away, and it is expressly not a place in which to teach or hold reviews. Rather, it is a place in which faculty work with students on research projects is conducted and, like every Studio-X node, has a busy schedule of events, lectures, and exhibitions. For Wigley, employing students to do research at Studio-X is a way of ensuring that they expand their knowledge, getting hands-on experience and learning about design outside of the school without being taken advantage of as unpaid interns in commercial offices. Where events, lectures, and exhibitions within the university typically appeal to students, those at Studio-X are for graduates who work in the many firms in SoHo, Chelsea, or otherwise nearby as well as a broader public audience. To accommodate these tasks, Studio-X is set up as an endlessly reconfigurable space with easily demountable desks.

If the New York Studio-X has been a successful prototype, expanding beyond that location was Wigley’s next step. Let’s look at some of these nodes, starting with Studio-X-Beijing. Columbia has many reasons to be in Beijing, with China growing exponentially and a number of faculty members already working there. For example, in 2009 Steven Holl completed his “Linked Hybrid”, a Beijing complex that addresses the massive growth, rapid change, and the opening up of the country. Given the crowding in Beijing, it’s appropriate that Studio-X-Beijing is small and seemingly hidden away, located in a factory building in a new art zone near the historical center of the city. Although I mentioned that Studio-X facilities do not host study-abroad programs where students spend a semester or a year in a foreign country, Columbia does send visiting studios to the Studio-Xs for a week at a time, as part of a scholarship program in which every student who attends GSAPP is reimbursed for travel abroad with one studio during their final year of education. Thus, a number of studios have already visited Studio-X Beijing, even as it has held competitions, symposia, exhibits, events, all attracting hundreds of local people.

Studio-X-Rio is in an historic townhouse in the city center. It offers another set of conversations and events that revolve around Latin America and an expertise in emerging creativity from around the globe. Studio-X-Rio also allows us to glimpse at how these centers might work financially, by approaching business leaders interested in bringing creative approaches to Rio from the perspective of digital and network technology. Although digital and network technology is explicitly the focus of the Studio-X program as a whole, the key location for it is Rio, since that is what the local condition calls for and produces funding for.

The Amman, Jordan facility is not a Studio-X but rather a “lab,” considered part of the network, but smaller than a typical facility, a mini Studio-X, if you will. The Amman lab is the only one that functions within another larger Columbia University center, being opened within the Columbia University Middle East Research Center in March 2009. In contrast to Rio, the focus of the Amman lab is historic preservation. So for example, the staff might undertake the exploration of some ruins and how one might preserve them in tandem with the historic preservation faculty. Beyond the focus on historic preservation, there have also been architecture design studios visiting the downtown, urban planning studios in poor neighborhoods and other activities held there.

These three examples of Studio-X nodes give a general overview of how the global network functions, but essential to understanding it are the labs that the school has built. Again, these operate outside of the traditional curriculum to conduct research that pushes the bounds of what architecture is. One of the oldest and most well-known labs is the “Spatial Information Design Lab” (SIDL) run by Laura Kurgan and Sarah Williams. This lab specializes in applying the architect’s spatial expertise towards geographic and cartographic issues, tackling complex problems through visualization. The most well-known of their projects is “Million Dollar Blocks,” done in collaboration with the Justice Mapping Center. In this project the SIDL argues that reducing crime by focusing on the areas with the highest crime statistics can be a misguided approach. Instead, they conclude that it is important to focus on the neighborhoods that prisoners come from, as that is where crime begins. So they look at the addresses that felons come from and identify city blocks in which the government spends more than a million dollars per year to house residents. The resulting amp allows the government and private institutions to rethink where prevention efforts should be targeted.

Living Architecture Lab, run by David Benjamin and Soo-in Yang specializes in responsive architecture. The lab’s premise is to develop architecture that senses and responds to the world. For example, in South Korea they created Living Light, a pavilion with skin that glows and blinks in response to the local air quality. Together with the SIDL, they used air pollution sensors to track what the impact was on air quality in the city before and after restrictions were put in to limit pollution for the 2008 Summer Olympics. Although the Living Architecture Lab takes on big issues, they also understand the virtues of small scale and published a set of books on flash projects to explore particular projects in architecture done for under a thousand dollars, which in the US is not a lot of money.

The Network Architecture Lab

For the last section of the lecture, I wanted to focus on my lab, the Network Architecture Lab, founded in 2006. The lab’s premise is that the impact of digital, networking technology needs to be investigated carefully, even skeptically. Our sense of space has transformed completely and virtually every facet of our lives, from politics to friendship to how we watch movies to how we think of sex has been subject to transformation. I’m agnostic, if you will, in regard to technology and, indeed skeptical of the impact all of this is having on our lives.

The Network Architecture Lab’s focus is largely on invisible architecture, on the transformation that has left no visible traces on the city around us. The transformation involves what media theorist Paul Dourish calls “Hertzian Space,” the spatial dimension of the electromagnetic spectrum produced by our devices, e.g. the space of radio waves, the space of wireless technology, and even the maps traced by hidden network cables.

Let’s take a look at a series of projects that we have done. First, take the Infrastructural City, a book that I edited and that the lab designed and produced maps for in 2008. This book is the culmination of years of research into Los Angeles, the city that epitomized the big infrastructure of the modern era, existing only because of aqueducts that bring the water from hundreds of kilometers away as well as the over eight hundred kilometers of freeways within it. The city exists because of electric lines that bring it power all the way from both Nevada and Washington State. This is a city that does not naturally exist, it is a city that is on a massive life support mechanism. And yet, in a way, every city is like that. Vilnius, after all, faces similar challenges, such as having to rely on gas from overseas. In the book, I hypothesize that you cannot build that kind of infrastructure anymore in a developed country. There is a mass of political impasse that prevents it. Rich or poor, people don’t want big infrastructure projects in their yards. Any time a big project is proposed, incredible road blocks are set up against it . Politically speaking, this is a major problem for us as a country. But what’s interesting is that some planners understand this condition and incorporate it into their work. In Los Angeles, planners realized that if they add another lane to an existing freeway that will cost a billion dollars a mile. In seven years, however, the freeway will clog as badly as it had clogged before the lane was added. So instead, they incorporate the traffic jam into their strategy, understanding that people generally will not live more than 45 minutes away from where they work. If the jam means it’s harder to go the extra distance, then people move or get new jobs. So there is a kind of feedback effect where the jam itself is no longer seen as a problem to solve but rather as a condition that can be incorporated in the planning process. As we look at the city we see more of these kind of feedback effects in the development of smart infrastructures, that is traditional infrastructure augmented with sensors and computers.

Another project we did was a book called “Networked Publics,” initially begun at the Annenberg Center for Communication at the University of Southern California (University of Southern California) and finished at Columbia. I was hired at the Center for a year, right before I came to Columbia, to run a research group looking at sociological and cultural aspects of what today’s technology was bringing us. Moreover, as we developed the book, we augmented it with a series of panels on the book’s topics at Studio-X, working with Domus magazine to create a hybrid lecture with audience interacting with us using live streams. People in places like Helsinki, Chicago, Washington D.C., Columbia, and Australia watched it and responded using Twitter. In turn, the response was fed back into the event in the form of questions that the panelists responded to. After the panels, we asked people throughout the world to respond with unsolicited pieces which we then gathered together, reviewed and worked with Domus magazine, which published them on their website. So this became a kind of feedback effect in which we tried to incorporate as many ideas as we could.

At times we do actually produce more familiar designs on an urban scale. In 2010, we competed in a worldwide competition to redesign Long Island, New York. Our proposal was that if you want to redesign Long Island, you need to think about it in terms of infrastructure, ecology and networks, and to undo some very commonly held ideas about what you must do with urban planning. First of all, we noticed that Long Island still gets its water from an aquifer underneath it. We decided that since the aquifer was currently being polluted out of existence and that getting water from elsewhere was prohibitively expensive, we’d have to decide which part of the aquifer to keep and figure out a way to rapidly depopulate the land above it. We also found out that some areas of Long Island are thriving and others not. Many of the areas that are not doing well are above the aquifer. So we proposed that rather than trying to revive these communities, we should abandon them through tax incentives and regional planning in favor of densifying some of the older suburbs close to the city that are now increasingly being populated by recent immigrants. These suburbs are already places to which Indian, Portuguese, and Spanish immigrants move. We decided on a few key overall moves. First, we suggested that within these suburbs, we could also mimic that strategy of selective depopulation that we introduced on the island-wide scale. We’d turn the depopulated parts into parks while densifying the centers. We also proposed that the ethnic identity of the suburbs be celebrated so that the centers would become filled with radical typologies from immigrant culture, such as, for example a mini driving golf courses on top of a parking garages. This seems odd to us, but if you are in a Korean neighborhood in Korea or in the United States, it is absolutely normal. In other words, we set out to promote ethnic diversity across the territory, not across an individual community, thus encouraging these neighborhoods to be greater communities while also serving as destinations for dining, shopping, and entertainment.

Finally, I’ll briefly mention a project we took on at the New Museum of Contemporary Art in New York. We were invited to participate in “The Last Newspaper” exhibit, a show in which artists looked at the fate of the newspaper. My collaborator Joseph Grima and I decided to focus on how newspapers’ readership is changing. We are increasingly reading newspapers on devices—iPads, smart phones, and so on—and we’re getting very targeted ideas of the news, algorithms ensure that we see only things we want to read. Moreover, news is becoming something very private. In the past, people would read newspapers in public, thus performatively announcing the importance of being an informed citizen. So we sought to find ways to revive the newspaper. Joseph had noticed how in China people read newspapers posted on walls outside. I also remembered from my childhood in Chicago. We found that newspapers were often hung in public on walls outside newspaper offices, so that people could read them. In the 19th century, with the spread of mass literacy and cheap paper, cities like New York and Paris were filled with literature, filled with words. So we imagined a newspaper that could be hung in public and established a newspaper office in the gallery, bringing staff, an office, even a typewriter on which the visitors to the show were asked to write letters to the editor. I decided that we really needed to think not of a new newspaper each week, but a new section each week, edited by a different group to reflect on the role of the newspaper in shaping architecture and urbanism. Taking some examples, Netlab produced the “City” section to look at the way the New York Times operated in New York City during the blackout in 1977, how they interacted with the public and continued to be published and what its effects were. The concept was to work with the graphic designer Neil Donnelly to imagine that this paper wouldn’t just be read, but would also be hung in public. Each one of these is an individual issue, with a different graphic layout and is designed to be read on the wall. We imagined we’d post this all over New York City, although it turned out that didn’t happen. We found out, after starting the project, that it was actually illegal to do that, except on temporary walls surrounding construction sites. The problem there is that the posters hung on those walls are done with the permission of the building contractor, which often were mafia-controlled. So, the options seemed to be that we could have our knee caps broken by the mafia or fined 35,000 dollars per incident. We applied to the Metropolitan Transit Authority to have it hung on various job sites they had and eventually we made it through the paperwork, but by then it was November and it was too cold. We also underestimated how long it would take to hang these things, because it’s actually quite hard to hang them. In the end we reflected on how the difficulty of posting such things changes the relationship of public documents and the city.

The point of the New City Reader was that we wanted to investigate the interaction of media, the city, and architecture. After all, the buildings by Zaha Hadid, Frank Gehry and so forth are being built partly to appear in the news, and partly to get the builder’s name in the news. So newspapers and architecture are very tied together. Newspapers are players within the city. They play a key role in the urban realm. And, of course, with newspapers being greatly impacted by new media, we were interested in how these things would work together.

This talk has been a brief overview of the Studio-X and labs initiatives at Columbia. Together I hope that this provides an understanding of how the education of the expanded architect might progress and how GSAPP is experimenting with new models of education and research.

Šiandien kalbėsiu apie švietimą architektūroje, o ypač apie “Studio-X” iniciatyvą Kolumbijos universiteto miestų planavimo ir išsaugojimo magistrantūros bei doktorantūros mokykloje (toliau – “MPIMDM”). Įdiegta dekano Marko Wigley’io, ši iniciatyva tapo globalizacijos švietime ir ryšio tarp architektūros ir mokslinių tyrimų pavyzdžiu.

Wigley’is kviečia rengti “platesnio profilio architektą”, ragina studentus mąstyti peržengiant to, kas tradiciškai laikoma įmanomais dalykais architektūroje, ribas, o radikalų mąstymą, išsiugdytą architektūros švietimo įstaigoje, pritaikyti ir kitose srityse, net ir visai nesusijusiose su užstatymo aplinka. Antroje savo paskaitos dalyje aptarsiu vieną pavyzdį, kaip minėtas platesnio profilio architektas gali pasireikšti architektūros praktikoje, vadinamoje Network Architecture Lab laboratorija. Pasaulinis kontekstas yra labai svarbus Wigley’iui, ir jis teigia, kad “jeigu mes negalvojame apie ateitį, ją siedami su visais besivystančiais pasaulio regionais, tada mes iš viso apie ją negalvojame.” Didžiuosius geopolitinius pokyčius pasaulyje – globalizaciją, Kinijos iškilimą, Sovietų Sąjungos žlugimą, sparčią Brazilijos, Indijos ir panašių valstybių plėtrą – Wigley’is laiko ne tik politinėmis ir ekonominėmis transformacijomis, bet ir veiksniais, lemiančiais mąstymo bei architektūros pokyčius. Jungtinių Valstijų Kolumbijos Universitete taip pat įvyko fundamentalūs pokyčiai. Dar XX a. septintame deš. absoliučiai visi architektūros programos dėstytojai ir studentai buvo baltieji amerikiečiai vyrai. Dabar tiek personalas, tiek studentai gali pasigirti kur kas didesne įvairove, nes čia studijuoti atvyksta žmonės iš viso pasaulio. Todėl ir poreikis nagrinėti globaliuosius pokyčius tapo kur kas aktualesnis, tad Wigley’is siūlo, kad užuot toliau buvęs kolonijine švietimo įstaiga su padaliniais įvairiose pasaulio šalyse, Kolumbijos universitetas galėtų plėstis, tapti tam tikra bendradarbiavimo platforma.

Studio-X

Wigley’io atsakas į visa tai buvo “Studio-X” (“X” šiame pavadinime reiškia “eksperimentinis”) programos įkūrimas. Pasaulinį “Studio-X” tinklą sudaro megapoliuose, tokiuose kaip Niujorkas, Pekinas, Tokijas, Amanas, Mumbajus, Rio de Žaneiras, Maskva ir Johanesburgas, įsikūrę centrai. Kiekvienas toks centras nėra tradicinė studentų rengimo ar auditorijų, bet, veikiau, tarptautinės sąveikos vieta, galerija, biblioteka, paskaitų erdvė, posėdžių kabinetas, biuras ar kavinė. Visi šie elementai įvairiais būdais jungiasi tarpusavyje, suformuodami kiekvieną “Studio-X” centrą, kuris, savo ruožtu, tampa erdve kūrybiniams sprendimams plėtoti, aktualiausioms miestų kaitos problemoms spręsti. Bent jau teoriškai, kiekvienas toks centras yra svarbus, tampa veiklos centru. Kitaip negu, sakykime, Niujorko Universiteto Tarptautinės programos, šie centrai nėra skirti lyderystei, švietimui ir tyrimams skleisti pasaulyje ar užtikrinti erdvę studijų užsienyje programoms įgyvendinti, bet, veikiau, padeda suprasti, kad, nors Kolumbijos Universitetas turi ką pasiūlyti, jis taip pat turi ir ko pasimokyti iš kitų. Plėtodamas “Studio-X” centrų tinklą, universitetas tobulėja kaip mokymo įstaiga.

Šiose fotografijose matome pasaulinio “Studio-X” centro prototipą, esantį Niujorko Soho rajone. Jis buvo įkurdintas Varick Street gatvėje, 180, pastate, kuris jau pats savaime yra pažangiausio architektūrinio mąstymo inkubatorius šalyje – jame įsikūrusios tokios architektų studijos kaip “2 X 4 Design”, Michael Sorkin, OMA, Toshiko Mori ir kiti. Taigi pati “Studio-X” vieta yra gana nepatogi vykstantiems iš universiteto miestelio, iš kurio ten nukakti trunka 40 minučių; tai tikrai nėra vieta, kur būtų patogu mokyti studentus ar rengti peržiūras. Tačiau “Studio-X” – tai vieta, kurioje dėstytojai dirba su studentais prie tyrimo projektų ir, kaip ir kiekviename “Studio-X” centre, čia vyksta labai daug renginių, paskaitų, parodų. Priimdamas studentus dirbti prie “Studio-X” tyrimų, Wigley’is siekia praplėsti jų žinias, suteikti galimybę įgyti vertingos darbo patirties ir kai ką sužinoti apie projektavimą už mokyklos ribų, neišnaudojant jų neapmokamose praktikose, kurios būdingos komerciniams [architektūros] biurams. Nors paprastai universiteto renginiai, paskaitos ir parodos būna skirti tik studentams, “Studio-X” orientuojasi į magistrantus ir doktorantus, kurie jau dirba daugybėje Soho, Čelsio ir kituose gretimuose rajonuose įsikūrusiuose architektų biurų, taip pat į visuomenę. Siekiant šių tikslų, “Studio-X” centras yra įrengtas kaip nuolat keičiama mokymo erdvė su lengvai išmontuojamomis darbo vietomis.

Taigi, Niujorko “Studio-X” tapo itin sėkmingu prototipu, ir tolesnė plėtra už jo ribų buvo kitas, Wigley’io numatytas žingsnis. Dabar pamatysime keletą kitų centrų, pradedant nuo “Studio-X” Pekine. Priežasčių, kodėl kitas “Studio-X” centras turėjo būti įsteigtas Kinijoje, buvo daug, įskaitant ir sparčią šios šalies plėtrą, ir tai, kad čia jau dirbo nemažai mūsų akademinio personalo narių. Pavyzdžiui, 2009 m. Stevenas Hollas baigė savo “Sujungto hibrido”, tam tikro komplekso Pekine, projektą, kuriuo siekė spręsti spartaus augimo, milžiniškų pokyčių ir šalies atsivėrimo klausimus. Turint galvoje daugiamilijoninį Pekino kontekstą, ko gero, nieko keista, kad “Studio-X” centras Pekine yra gana nedidelis ir tarsi paslėptas, įsikūręs buvusiame gamyklos pastate, naujai formuojamoje menų zonoje, greta istorinio miesto centro. Nors pirmiau minėjau, kad “Studio-X” įstaigos nepritaikytos studijų užsienyje programoms, kai studentai svetur mokosi semestrą ar net metus, vis dėlto Kolumbijos Universitetas siunčia studentus į savo “Studio-X” centrus, tačiau tik savaitei, ir ši kelionė į vieną iš centrų paskutiniaisiais studijų metais jam arba jai yra apmokama, kaip MPIMDM programos stipendijos dalis. Taigi, “Studio-X” centrą Pekine jau aplankė gana nemažai studentų, čia rengiami konkursai, simpoziumai, parodos, vyksta kiti renginiai, pritraukiantys ir šimtus vietos gyventų.

“Studio-X” centras Rio de Žaneire yra įsikūręs istoriniame name miesto centre. Čia taip pat vysta daugybė diskusijų ir renginių, susijusių su Centrinės Amerikos regionu, siūloma susipažinti su kylančiu kūrybiškumu visame pasaulyje. “Studio-X” centras Rio taip pat leidžia pastebėti, kaip šie centrai gali veikti finansine prasme, pritraukdami [vietos] verslo lyderius, suinteresuotus, kad Rio de Žaneirą pasiektų kūrybinės prieigos, ypač skaitmeninių ir ryšio technologijų srityje. Nors toks dėmesio sutelkimas į skaitmenines bei ryšio technologijas iš tiesų reiškia dėmesį ir visai “Studio-X” programai, dėl Rio de Žaneire susidariusių tam tikrų sąlygų būtent ši sritis yra svarbiausia ir teikia finansavimą.

“Studio-X” Jordano sostinėje Amane veikiau yra ne centras, o tik laboratorija, nes, nors yra viso centrų tinklo dalis, tačiau kur kas mažesnė nei tipinė “Studio-X” įstaiga, tarsi savotiška mini jos versija. Amano laboratorija yra vienintelė įstaiga, veikianti kaip kito, didesnio Kolumbijos Universiteto centro, Kolumbijos Universiteto Artimųjų Rytų tyrimų centro, atvėrusio duris 2009 m. kovą, dalis. Skirtingai nuo Rio de Žaneiro, Amane daugiausiai dėmesio skiriama paveldo apsaugai. Todėl “Studio-X” personalas, pavyzdžiui, gali dalyvauti kokių nors pastatų liekanų tyrinėjimuose ir, dirbdamas kartu su vietos istorinio paveldo apsaugos darbuotojais, mokytis, kaip juos išsaugoti. Be minėto dėmesio istorinio paveldo apsaugai, čia taip pat rengiamos architektūrinio projektavimo studijos, aplankant miesto senamiestį, miestų planavimo studijos, orientuotos į vargingus regionus, ir kita veikla.

Iš šių trijų pavyzdžių matyti bendras “Studio-X” centrų vaizdas, kaip šis pasaulinis tinklas veikia, tačiau labai svarbios yra ir mokyklos įsteigtos laboratorijos. Kaip ir centrai, jos veikia nepaisydamos tradicinės studijų programos, jose atliekami tyrimai praplečia architektūros supratimo ribas. Viena seniausių ir geriausiai žinomų laboratorijų yra Spatial Information Design Lab (SIDL), kuriai vadovauja Laura Kurgan ir Sarah Williams. Šios laboratorijos specializacija – architekto erdvinių žinių taikymas geografiniams ir kartografiniams sprendimams, kompleksinis problemų sprendimas, taikant vizualizaciją. Vienas iš žinomiausių laboratorijos projektų - “Million Dollar Blocks”, atliktas bendradarbiaujant su Justice Mapping centru. Šiuo projektu SIDL įrodinėja, kad mėginimas spręsti nusikalstamumo problemą, susitelkiant į didžiausia nusikaltimų statistika garsėjančius rajonus, gali būti klaidingas. Projekte daroma išvada, jog itin svarbu yra susitelkti į tuos rajonus, iš kurių nusikaltėliai kilę, nes būtent ten ir prasideda nusikalstamumas. Taigi, tyrėjai nagrinėja vietas, kuriose nusikaltėliai užauga, identifikuoja miesto kvartalus, kuriems apgyvendinti vyriausybė kasmet išleidžia daugiau nei po milijoną dolerių. Šio tyrimo rezultatai leidžia vyriausybei ir privačioms institucijoms iš naujo apsvarstyti, kur turėtų būti nukreiptos nusikalstamumo prevencijos pastangos.

Kita laboratorija, Living Architecture Lab, kuriai vadovauja Davidas Benjaminas ir Soo-in Yangas, specializuojasi atliepiamosios architektūros srityje. Šios laboratorijos tikslas – kurti architektūrą, kuri vienaip ar kitaip reaguoja į aplinką. Pavyzdžiui, Pietų Korėjoje jie sukūrė Gyvosios šviesos (Living Light) paviljoną, kurio apvalkalas švyti ir žybčioja, reaguodamas į vietos oro kokybę. Kartu su SIDL, jie panaudojo oro užterštumo sensorius, fiksuojančius, kokią įtaką miesto oro kokybei padarė taršos apribojimai, įvesti prieš 2008 m. vasaros olimpines žaidynes. Nors Living Architecture Lab paprastai imasi spręsti dideles problemas, jie taip pat supranta, jog svarbūs gali būti ir maži dalykai. Todėl išleido seriją knygų apie momentinius [trumpalaikius] projektus (flash projects), nagrinėjančią tam tikrus architektūrinius projektus, kurie buvo parengti už mažiau nei 1000 dolerių, kas JAV nėra dideli pinigai.

Network Architecture Lab

Likusią paskaitos dalį norėčiau skirti pasakojimui apie savo laboratoriją – Network Architecture Lab, įkurtą 2006 m. Esminė jos įsteigimo prielaida buvo ta, kad skaitmeninių, ryšio technologijų poveikis turėtų būti nuodugniai ištirtas, netgi laikantis skeptiško požiūrio. Pastaraisiais metais visiškai pasikeitė mūsų erdvės suvokimas ir tai smarkiai paveikė kiekvieną gyvenimo aspektą, pradedant politika, draugyste, filmų žiūrėjimu ir baigiant netgi tuo, ką manome apie seksą. Laikausi gana agnostinio požiūrio į technologijas, jeigu galima taip pasakyti, ir tikrai esu skeptiškas dėl jų daromos įtakos mūsų gyvenimams.

Šios laboratorijos veikla daugiausiai nukreipta į nematomą architektūrą, į transformaciją, kuri nepalieka jokių matomų pėdsakų mus supančiame mieste. Ši transformacija apima tai, ką medijų teoretikas Paulas Dourishas vadina “Herco erdve”, elektromagnetinio spektro, kurį skleidžia mūsų skaitmeniniai prietaisai, erdvine dimensija, pavyzdžiui, tai gali būti radijo bangų ar bevielių technologijų erdvė, ar net paslėptų ryšio kabelių žemėlapis.

Trumpai apžvelgsiu mūsų įgyvendintus projektus. Pirmiausia, tai Infrastructural City – knyga, kurią redagavau, o 2008 m. Laboratorija sukūrė ir pagamino jai žemėlapius. Ši knyga apvainikavo ilgametį tyrimą, vykdytą Los Andžele, mieste, įkūnijusiame moderniosios eros stambiąją infrastruktūrą, mieste, egzistuojančiame tik dėl sudėtingos vandentiekio sistemos, kuria vanduo atkeliauja į jį šimtus kilometrų, taip pat daugiau nei 800 kilometrų ilgio greitkelių, esančių pačiame mieste. Los Andželas egzistuoja tik dėl elektros perdavimo linijų, kuriomis elektra atvedama net iš Nevados ir Vašingtono valstijų. Tai miestas, kuris negali egzistuoti natūraliai, kuris yra tarsi prijungtas prie milžiniško gyvybės palaikymo aparato. Ir vis dėlto, pažvelgus atidžiau, kiekvienas miestas yra toks. Galiausiai net Vilnius susiduria su panašiais iššūkiais, pavyzdžiui, kad ir tuo, jog yra priklausomas nuo importuojamų dujų. Šioje knygoje keliu hipotezę, kad išsivysčiusioje šalyje pastatyti tokio tipo infrastruktūrą tapo tiesiog neįmanoma. Tam trukdo tam tikra milžiniška politinė aklavietė. Ir turtingi, ir vargšai nebenori stambių infrastruktūrų savo kieme. Vos tik pasiūlomas didesnis projektas, jis susiduria su neįtikėtinomis kliūtimis. Kalbant politiškai, tai didelio masto, visos šalies problema. Tačiau įdomiausia, kad kai kurie projektuotojai tai supranta ir į tai atsižvelgia savo darbe. Pavyzdžiui, Los Andželo planuotojai suprato, kad norint papildyti esamą greitkelį dar viena eismo juosta, tai kainuotų po milijardą dolerių už kiekvieną mylią. Tačiau po septynerių metų net ir taip praplatintas greitkelis imtų kimštis lygiai taip pat, kaip ir prieš rekonstrukciją. Todėl, užuot ėmęsi kelio remonto, į savo naują plėtros strategiją jie įtraukė eismo kamščius, darydami prielaidą, kad žmonės paprastai negyvena būstuose, kurie yra nutolę nuo jų darboviečių daugiau negu 45 minučių atstumu. Ir jeigu transporto kamštis apsunkina ir taip didelio atstumo įveikimą, žmonės paprastai kraustosi kitur arba keičia darbą. Taigi, kai į transporto kamštį nebežiūrima kaip į problemą, kurią reikia spręsti, bet, veikiau, kaip į tam tikrą sąlygą, į kurią tenka atsižvelgti planavimo procese, įvyksta tam tikras atvirkštinio ryšio efektas. Atidžiau pažvelgę į miestą, pastebėtume ir daugiau tokių atvirkštinio ryšio efektų plėtojant išmaniąsias infrastruktūras, t.y. tradicines infrastruktūras, tik papildytas įvairiais jutikliais ir kompiuteriais.

Kitas mūsų projektas buvo knyga Networked Publics, kurią pradėjome Pietų Kalifornijos universiteto Anenbergo komunikacijų centre, o baigėme jau Kolumbijos universitete. Minėtas centras pasamdė mane metams (kaip tik prieš pat atvykstant į Kolumbijos universitetą) vadovauti tyrimų grupei, kuri nagrinėjo šiuolaikinių technologijų poveikio sociologinius bei kultūrinius aspektus. Be to, rašydami šią knygą, dar papildėme ją diskusijų serijos medžiaga ta pačia tema. “Studio-X” centras, bendradarbiaudamas su žurnalu “Domus”, organizavo hibridinę paskaitą, kurios klausytojai dalyvavo ir bendravo su mumis tiesioginės transliacijos metu. Žmonės Helsinkyje, Čikagoje, Vašingtone, Kolumbijos [universitete] ir Australijoje tai žiūrėjo ir atsiliepė per Twitterį. Grįžtamasis ryšys [klausytojų reakcija] buvo gautas klausimų, į kuriuos atsakė diskusijos dalyviai, forma. Po diskusijų paprašėme žmonių iš viso pasaulio pareikšti savo nuomonę apie savanoriškai pasirinktas jos dalis [atkarpas], kurias mes vėliau surinkome, apžvelgėme, o žurnalas “Domus” tai patalpino savo internetiniame portale. Taigi, visa tai turėjo tam tikrą grįžtamojo ryšio poveikį, kuriame mes pamėginome apjungti kuo daugiau idėjų.

Kartais mes rengiame ir įprastesnius projektus miesto masteliu. 2010 m. dalyvavome pasauliniame konkurse Niujorko miestui priklausančiai Long Ailendo salai pertvarkyti. Savo pasiūlyme iškėlėme idėją, kad norint pertvarkyti Long Ailendą, pirmiausia reikia sutelkti dėmesį į jos infrastruktūrą, ekologiją ir ryšius bei tinklus, taip pat atsisakyti kai kurių įprastų idėjų, susijusių su tuo, ką privalu padaryti planuojant miestą. Visų pirma, pastebėjome, kad Long Ailendo sala aprūpinama vandeniu iš po ja esančio požeminio vandeningojo sluoksnio. Kadangi šiuo metu vanduo yra smarkiai užterštas, o atvesti jį iš kurios nors kitos vietos – nedovanotinai brangu, svarbu nuspręsti, kurią vandeningojo sluoksnio dalį toliau naudosime, ir išsiaiškinti, kaip kuo skubiau būtų galima kitur perkelti viršum jos gyvenančius žmones. Taip pat išsiaiškinome, kad kai kurios Long Ailendo dalys tiesiog klesti, o kitos – ne. Nustatėme, kad būtent tos salos vietos, kurioms sekasi prastai, ir yra virš vandeningojo sluoksnio. Taigi, užuot mėginę atgaivinti tas bendruomenes, pasiūlėme pasinaudojant mokesčių lengvatomis ir regiono planavimu jas tiesiog iškraustyti į senuosius priemiesčius, kuriuose gyventojų skaičius pastaruoju metu smarkiai auga dėl naujų migrantų, taip šias miesto dalis dar labiau sutankinant. Šie priemiesčiai jau ir taip yra vietos, į kurias atvyksta nauji migrantai indai, portugalai ir ispanai. Taip pat apsisprendėme dėl keleto bendro pobūdžio veiksmų. Pirma, pasiūlėme šiuose priemiesčiuose imituoti tą selektyviosios depopuliacijos strategiją, kurią pristatėme visos salos mastu. Tas jos dalis, kuriose gyventojų skaičius sumažėjęs, paversti parkais, o centrus sutankinti. Taip pat pasiūlėme atsižvelgti į priemiesčių etninį identitetą, kad centruose rastųsi radikalių tipologijų, būdingų migrantų kultūrai, pavyzdžiui, mini golfo laukai ant daugiaaukščių parkingų stogų. Gal iš pirmo žvilgsnio atrodo keista, bet, jeigu buvote Korėjoje ar Jungtinėse Valstijose, kur gyvena daug korėjiečių, tai tampa visiškai normalu. Kitaip sakant, mėginome paskatinti etninę įvairovę visoje teritorijoje, ne tik atskirose bendruomenėse, tuo pačiu paskatindami šiuos rajonus tapti geresnėmis bendruomenėmis ir išlaikyti vietas, kur galima papietauti, apsipirkti ar pramogauti.

Galiausiai, trumpai paminėsiu vieną projektą, kurį įgyvendinome su Naujuoju šiuolaikinio meno muziejumi Niujorke. Buvome pakviesti dalyvauti “Paskutiniojo laikraščio” parodoje, kurioje menininkai buvo kviečiami pažvelgti į [tradicinio] laikraščio likimą. Mano kolega Josephas Grima ir aš nusprendėme susitelkti ties tuo, kaip keičiasi laikraščio skaitytojai ir pats skaitymas. Dabar mes vis dažniau laikraščius skaitome įvairiuose įrenginiuose – iPaduose, išmaniuosiuose telefonuose ir pan. Dėl to žinios mums pateikiamos labai tendencingai, panaudojant tam tikrus algoritmus, kad pamatytume tik dalykus, kuriuos mes norime skaityti. Maža to, žinios tampa labai suasmenintos. Anksčiau žmonės skaitydavo laikraščius viešumoje, kažkaip net teatrališkai tuo parodydami kitiems, jog yra informuoti piliečiai. Taigi, ėmėme ieškoti būdų, kaip atgaivinti laikraštį. Kartą Josephas pastebėjo, kaip Kinijoje žmonės skaito laikraščius, pakabintus lauke ant sienos. Tą ir aš prisiminiau iš vaikystės Čikagoje. Pastebėjome, kad laikraščiai dažnai iškabinami ant sienų greta įvairių naujienų agentūrų, kad žmonės galėtų juos perskaityti. XIX a. pasaulyje plintant masinam raštingumui ir pingant popieriui, didieji miestai, kaip antai Niujorkas ar Paryžius, būdavo pilni literatūros, pilni žodžių. Taigi, mes įsivaizdavome laikraštį, kurį galima iškabinti viešai, ir galerijoje įrengėme redakciją su jai būdingu personalu, biuru, netgi spausdinimo mašinėle, kuria parodos lankytojai buvo kviečiami parašyti laišką leidėjui. Nusprendžiau, kad mums iš tiesų reikia galvoti ne apie naują laikraščio [numerį] kiekvieną savaitę, o apie naują jo skyrių, kurį redaguotų skirtingos žmonių grupės ir kuris atspindėtų laikraščio vaidmenį formuojant architektūrą ir urbanizmą. Pavyzdžiui, Netlab pristatė skyrių “Miestas”, kuriame apžvelgė, kaip Niujorke veikė New York Times per elektros energijos tiekimo sutrikimą 1977 m., kaip jie bendravo su visuomene, užtikrino, kad nesutriktų laikraščio leidimas, koks buvo viso šito poveikis. Mūsų koncepcija buvo pasitelkus grafikos dizainerį Neilą Donnelly’į įsivaizduoti, kad šis laikraštis būtų ne tik skaitomas, bet ir pakabintas viešumoje. Štai atskiri jo numeriai su skirtingais maketais, pritaikyti skaitymui ant sienos. Planavome juos iškabinti visame Niujorke, tačiau paaiškėjo, kad tai neįmanoma. Jau pradėję įgyvendinti projektą, sužinojome, kad kabinti laikraščius ant sienos yra nelegalu, išskyrus laikinųjų statinių [pavyzdžiui, statybos aikštelių] užtvaras. Pasirodo, esmė ta, kad plakatai ant tokių užtvarų yra kabinami tik su statybos rangovo leidimu, o jį neretai valdo kokia nors mafija. Taigi, kaip paaiškėjo, turėjome dvejopą pasirinkimą: kad būsime sučiupti mafijos ir kankinami [už tai, kad pakabinome laikraštį], arba nubausti 35 000 dolerių bauda už kiekvieną atvejį. Kreipėmės į transporto kompaniją Metropolitan Transit Authority, kad leistų iškabinti laikraštį įvairiose jai priklausančiose vietose ir galiausiai sutvarkėme visą, su tuo susijusį popierizmą, bet atėjo lapkritis ir orai atšalo. Taip pat neįvertinome, kaip ilgai užtruksime, kabindami tuos laikraščius, nes iš tiesų tai nepaprastai sunkus darbas. Galiausiai susimąstėme, kaip visi šie sunkumai keičia santykį [požiūrį į] oficialius dokumentus ir patį miestą.

New City Reader pagrindinė idėja buvo ta, kad norėjome ištirti santykį tarp žiniasklaidos, miesto ir architektūros. Pagaliau, juk Zahos Hadid, Franko Gehry’io ir panašaus lygio meistrų statiniai iš dalies statomi dėl to, kad apie juos praneštų žiniose, iš dalies, kad statytojo vardas sušmėžuotų naujienose. Taigi, laikraščiai ir architektūra – tampriai tarpusavyje susiję. Laikraščiai yra vieni iš veikėjų mieste. Čia jie vaidina svarbų vaidmenį. Ir, žinoma, kadangi laikraščiams itin stiprų poveikį daro naujosios žiniasklaidos priemonės, mus domino ir tai, kaip jos visos veiktų kartu.

Šioje paskaitoje trumpai apžvelgiau “Studio-X” centrų ir laboratorijų iniciatyvas Kolumbijos universitete. Tikiuosi, kad visa tai padės suprasti, kaip galėtų būti ugdomas minėtas “platesnio profilio” architektas ir kaip MPIMDM eksperimentuoja su naujais švietimo ir tyrimų modeliais bei galimybėmis.

I was asked to talk about education and as Linas says in [his] introduction , I am active in different places: besides being an associate partner at Henning Larsen and having worked for Foster and Partners, I have been teaching since I finished my studies. I taught at three institutions for 8 years–The Royal Danish Academy of Fine Arts, The Bartlett School of Architecture and Lund School of Architecture. I also realized that my practice has become a kind of teaching institution on its own. From such a perspective MAP (Manual of Architectural Possibilities) is also some type of a school. Therefore I wanted to look at myself as an educator, asking–how do I teach, what do I teach and why do I teach?

I tried to organize my teaching activities, in which I use different definitions for how and why I do it. For example, for the last five years I do workshops instead of running a studio in the Royal Danish Academy. Those workshops are seven days of very intense work with a very specific scenario and agenda. At Lund School of Architecture I am heading a design studio for Extreme Environments and Future Landscapes masters course. Our studio specializes in this field and the course spans throughout the full semester. I teach undergraduate students in Unit 3 of a bachelors course at the Bartlett School of Architecture, where there are always two semesters. The span is thus very long , which also means that the mode of teaching is subject to changes over time. MAP on its own lasts six months, from day zero to the date it is sent to the printers. The studio of the Extreme Environments and the Institute of Architecture are sort of parts of each other. The projects that we do there often get a lot of students and interns engaged. They have become a very interesting dimension of the education, actually not only for them, but also for me.

Workshops

If I had to give a tagline for these workshops, it would be “Education as a Positive Disruption“. Why do I say that? The workshops that I teach at the Royal Danish Academy of Fine Arts normally take place at a time when students are starting to form an idea of the building that they would like to design. Usually they have been to the site and tried to define the program. But they have not yet gotten very far with their drawing. The agreement is that they come in and create a bit of chaos during the workshop period. What type of chaos? It goes in different directions. Usually one works more or less on one’s own during the semester project–that is the tendency in the Royal Danish Academy of Fine Arts. You have time to negotiate and discuss your ideas, you think a lot, you draw. But sometimes it gets difficult to get those ideas onto paper. My attitude is to do the exact opposite–in order to provide the students with a broad pallet of different tools, with which they can react to a project scenario or a methodology. So we concentrate on one aspect of every project, we put everybody together in one room, we work 17 hours a day for seven days, although it is less in reality–there is introduction on the first day, the last day is for the critique–so actually they have five days to do this. We work backwards, almost like reverse engineering–what is it that you would like to focus on, what is it that you would like to do, and then just do it. I would not want to talk about it, if it is not built in front of me. I do not want to hear about it, if it does not have any shape or form. The idea is to use your hands as direct tools to establish a dialogue within your methodology. We believe that tasks can also teach very directly. If you are thinking, “I want this façade to move and react to sunlight”–fine, but next time we see each other, I want to see something that does that, and if you have a problem, then we will try to figure it out. Very often I do not even know how it is going to be done, but we together find out technologies or solutions that would make it possible to do that. For four or five days it is a room that is very difficult to be in for everybody. But I also noticed that when people are working very close to each other, they inform each other. They see what each one does, share decisions or they help each other, one has tools that the others did not use, solutions that some discard, others picks up. Proximity and density are often amazing tools to stimulate a design process. In a way, you almost have to suspend disbelief and ask everybody to go into this unwritten contract that we are going to try and go by these rules for these seven days. It does not matter if you hate it at the very beginning or if you are fascinated by it, the idea is to embrace another way of doing architecture or generating methodology, which you may or may not use afterwards. At least you have another pallet in your toolbox, another way of doing things.

Why is this interesting? I think it is empowering for the student to believe that whatever he or she imagines might be possible. At the very beginning, they all think “I cannot build that” and after only five days reality is there. For example, one of the students was working at a site close to a lake. She was fascinated by how the structures and the walls were seeking and taking in humidity, creating crystalline structures. She wanted to see what happens if those structures of crystals were very big and started to take over the space. I showed her how different crystalline solutions could grow in front of you. Then she started to play with different sizes, how those spaces could be inhabited. She made films about how these crystals are growing and the different spatial qualities that can be appropriated. It suddenly reminded me of actual crystal caves underneath Mexico. Suddenly we realized that what she thought was a way to test possibilities, nature has done in thousands or millions of years. I think that the architectural language, established by the growth of something that is not necessarily in the same tradition of how we design spaces, can be very original.

I have to say that, throughout the years at the Royal Danish Academy of Fine Arts, I have created some kind of a tradition where people understand what they are getting into when they are going into this workshop, they understand that they are not going to sleep for a while. Although it was difficult in the very beginning: students could get very upset and be very irritated and would try to report me to the dean. It happens sometimes. I think that it must be due to another type of context, a tradition that has embedded their understanding of what education or work is. But most of the time it is fantastic and we learn together. Many of the times I do not even know how to find a solution for their idea or their vision. We have to go on this journey together. I have to start calling all the scientists or mechanics I know and say: “Hi, I have this student who wants to do this crazy stuff! How do we do this?”, and sometimes we just cannot come to a conclusion and that is fine, it is not a problem. I am not so interested in if it works in the end or not, but the fact that you are engaged fully in the desire to achieve that idea is very important. Other times there are things that seem impossible to me and students surprise me and realise them.

Extreme Environments and Future Landscapes

Extreme environments is a theme that is of great importance to me. I have to say that extreme environments have nothing to do with disaster scenarios. I am teaching a master course at the Lund University for fourth and fifth year students on extreme environments. I call it “learning by research and speculation”.

First I would like to explain why extreme environments are interesting. Unless you are willing to live in a space suit, you are going to have to engage with the difficulties of our environment. Some of them are very extreme. It does not have to be about weather. We know what happens during an earthquake in, for example, Haiti. Our surroundings are more and more often characterized by scenarios where people suddenly have to live in an unbuilt space and recreate their environment.