- INTRODUCTION

- LECTURES

- Miles Glendinning / The Hundred Years War: a ‘Long Century’ of Mass-Housing Campaigns Across the World

- Auguste Van Oppen and Marc Van Asseldonk / Open-Source Urbanism

- Tim Rienets / Less Is More? Urban Design and the Challenge of Shrinking Cities

- Adam Bobbette and Etienne Turpin / Aberrant Architecture: Typologies of Practice

- Matthias Rick / Fleeting Architecture ‒ Raumlabor’s Instant Urbanism

- ESSAYS

- Nerijus Milerius / Breaking Point: from Soviet to Post-Soviet City

- Benjamin Cope / A Reflection on Breaking Points in the Case of The Praga District of Warsaw

- Miodrag Kuč / Berlin. Becoming Normal?

- Mindaugas Pakalnis / Vilnius. The Challenge of Disintegration

- Siarhei Liubimau / Popular Urbanism and the Issue of Egalitarianism

- INTERVIEWS

- No Trust – No City / Matthias Rick Interviewed by Ona Lozuraitytė and Aistė Galaunytė

- The Man, Who Turned the Barbeque into the Center of the World / Benjamin Foerster-Baldenius

- Radicalising the Local / Jeanne Van Heeswijk Interviewed by Kotryna Valiukevičiūtė

- Learning-By-Doing / Laura Panait Interviewed by Arnoldas Stramskas

- Preserving the Generic / Kuba Snopek interviewed by Marija Drėmaitė

- A Permanent Anticipation of Uncertainty / Adam Bobbette interviewed by Arnoldas Stramskas

Partners of Raumlabor. Photo: raumlaborberlin, 2010

Good evening everyone, it is a great pleasure for me to be in Vilnius, it is the first time in my life and it is also the first time in my life that I have experienced minus 30 degrees today. In Berlin we have minus 16 at the moment. So let’s start. Before I forget I have to introduce our own book, it is called Acting in Public and we published it in 2008. This was our first book and in it we collected our first works and it is also a little bit about the background where we are coming from, why we are working and how we are working, and the things I will show today are mostly not in this book, so it will be a surprise for you if you have read this book – there will be something new. At the moment we are thinking about a new book because we’ve had a lot of new experiences with our works.

I always talk about ‘we’ – ‘we’ means 8 architect who are based in Berlin. We are working in a kind of collective way. We have the group called Raumlabor, which means space laboratory or spacelab in English. We understand our name as a programme; we see architecture as a tool, we work in the fields of architecture, urbanism and art and we like to experiment with the topic of architecture. We try to discover the borders, we are interdisciplinary, we work in different groups, in smaller units depending on the task, also with different specialists like scientists or sociologists, or carpenters, or also citizens, as you will see later.

And we like to work in the city because we see the city as the body, as an organism, it is not an image. It is something where we see our responsibility as an architect also to re-ask and improve how we would like to live together in the future. We don’t see our profession as solving problems, we like to make problems because making the problems is generating processes, we like these processes because city means process. Every city has its own identity, its own conditions we like to work with these conditions.

One quote: “On the inscrutability of this society, we must respond with a sense of proportion and the transformation of the impossible into the possible. Today’s society is so unpredictably productive because nobody knows what reactions it evokes… The individual must participate in society while dreaming of opportunities and be overwhelmed by complications. The Art of the next society is light and smart. It is evasive and binds with a joke. Its pictures, stories and sounds are attacking and have not been there”. This is Dirk Baecker, a philosopher from Germany in his essay “Fifteen Thesis for the Art of the Future” (2011). If you have questions, don’t hesitate to raise your hand and ask – I like discussions; you can interrupt me if you don’t understand something.

Public spaces is the field where we are working, where we like to work because it is a field of confrontation and a field of coincidence – you never know what happens, and it is a field, it is the space where we can discover the city and its identity. It is a space for the potentials, trading, market, acting and economic potentials to create new jobs, or also space of communication, to communicate with each other, and the space for your imagination, where you can try to create your own narratives and relation to the reality.

Image by Archigram, Instant City, 1960

Image by Archigram, Instant City, 1960

There is a very strong relation between what we are doing and where we will do it, so they are dependent on each other. You know a lot about the 60-70’s architecture of the city. This is the vision created by the group called Archigram, it is the Instant City. I just want to show you because these utopian ideas of that time influence us a lot. The idea of the Instant City was in the UK to go with the combination of different mobile architectures in the kind of sleeping boring cities in order to activate them. There are some tracks with containers and tents and then the Zeppelin came, parking on top of the city, folding out all its potentials in relation to the potentials of the city. There was a kind of research before developing a new cultural and attractive programme in connection to the citizens and their desires, and after a while they left and they left the transformed spaces ‒ what they expected was a glamorous and imaginative new society.

A quote from Archigram: “Glamour isn’t beauty or luxury; those are only specific manifestations for specific audiences. Glamour is an imaginative process that creates a specific, emotional response ‒ a sharp mixture of projection, longing, admiration and aspiration. It evokes an audience’s hopes and dreams and makes them seem attainable, all the while maintaining enough distance to sustain the fantasy.” What they also did was not only the transforming of city spaces, they also created networks. They started to connect cities with each other so that they could learn in the discussion from each other. They generated a kind of learning laboratories. “Technology is the answer! But what is the question?” ‒ Cedric Price, a friend of theirs asked. So what is the question today? I don’t like giving the answers but maybe some impulses to the start of what the question could be.

Cape Fear. Photo: raumlaborberlin, 2008

Cape Fear. Photo: raumlaborberlin, 2008

A project we did in 2008 in South Germany connected two cities. It was called “Cape Fear”, it was at the point where the river Neckar flows into the river Rhine, and it is a very dangerous current. This was for us the point of interest. On one side we have Mannheim, a nice city, and Ludwigshafen ‒ an ugly city on the other side of the river. Mannheim is a nice Baroque city, and Ludwigshafen is an industrial city. There is a huge industrial area ‒ the chemical plant BASF and the headquarters of BASF. It is a modern city, lots of new infrastructure, traffic highways through the city. What we did with “Cape Fear” was we wanted to connect the cities with a kind of big motive. We looked for a nice site – there was a market square next to an abandoned fire station. We developed an idea of building a submarine and connecting these two cities with this submarine. We opened up a casting office because we were looking for the 12 bravest citizens of Mannheim, who could help us build the submarine and who would be the crew afterwards. We wanted to make the route from the square, down the Neckar, around the very dangerous Cape, to Ludwigshafen to present the submarine to the Art gallery there.

Big Crunch. Photo: raumlaborberlin, 2011

Big Crunch. Photo: raumlaborberlin, 2011

The use what you find concept is also very important. Trash has a big value, and we like it because it is transformable and it is cheap. Very often art festivals have a very low budget, so we try to find ways of how to make incredible things. The festival “Architecture summer” in Darmstadt nearby Frankfurt in Germany last year asked us to build a pavilion in the centre of the festival where people can gather and where they can organize the parallel programme. With the local recycling company we collected the trash, shelves, sofas and so on for two days and left it in the main square in front of the modern wonderful theatre. It was a big scandal because the Darmstadt people were shocked as it was a newly designed square and then – full of trash! But the idea was to make a kind of argument, it was just after the tsunami catastrophe in Japan, and it is also our lifestyle creating a kind of catastrophe in the future, so this is an argument you can start thinking about.

Our idea was to build a huge tsunami wave which was attacking this glossy cultural object – the theatre – as a symbol. There was also a scaffolding structure underneath, the constructive idea. We started in collaboration with students in a 10-day workshop, building this big wave. There was a space inside, a kind of tube, it was very exciting for everybody. Very old citizens were thinking about the war – this trash mountain reminded them the big trash mountains after the bombings, and they were really shocked. When we finished it was very attractive and also a nice thing and nobody was complaining anymore. You can go inside, where you can find some working places where you can sit with a computer and work, also there is a bar in the back. It was summer, so we used the space outside in collaboration with a moving cinema. This was our experience in Darmstadt. After two weeks it was demolished and went into the trash again.

Drawing of Kitchen monument. raumlaborberlin, 2006

Temporary communities. Mobile urban activation. This is about another strategy. We developed a series of mobile urban activation units. It was also an invitation for the festival in 2006. This was in Duisburg, the harbour city at Rhine in the former industrial region of the Ruhr district in Germany. Industry collapsed as it did everywhere; this place was a coal mine and steel plant area. They tried for 20 years to transform this industrial landscape into a cultural landscape. The region was the European Capital of Culture in 2010 but this festival was in 2006. It is a region of 53 cities, with Duisburg being one of the biggest. The problem is the city centre ‒ people are leaving the city, and also the shops are leaving the city; you have abandoned shops, there is no connection and no authentic identity anymore.

The question of the festival and the theme was “What to believe in?” and the question to us was to create a kind of public installation, which recreates an authentic place to think about privacy and the public and the potentials. We used the monument as a tool ‒ it was our first idea because monuments or sculptures are very helpful for this, especially in this area where there are lots of ideas, they have Richard Serra’s crowning big hill here and they also have just around the corner a fountain in the city centre built by Joen Tinguel and Niki de Saint Phalle The name of the fountain is “Lifesaver”, it was built in the middle of the 90’s and became the icon of the city. We thought ok, the sculpture, the monument are very important for re-identification, and we used a kind of steel block building trailer we had transformed, we just covered the metal plates, and we used the metaphor of the Trojan horse, because the Trojan horse was the mobile monument in history which transported something hidden and exciting inside. We positioned it in a public space, and after 7 days there was a hidden door that opened; plastic came out and we inflated it – we created the fast ephemeral inflatable space. We filled it with a kitchen – the most public space in a private house, this is the place where you invite friends and foreigners to eat together, to talk, to discuss and to sit by the table together, play games or whatever. The kitchen and cooking is also a format which is understandable for everybody – for young and old people, students, businessmen, Turkish and Arabian people, people from Lithuania or Germany – it is very simple, everybody knows how to cook, everyone likes to eat, people know recipes from their grandmother. So what we did was in our research about the city we went around the neighbourhoods, we rang at the houses, and asked people “Would you like to be the host for a banquet for 100 people?” They were very afraid at first, but after we told them there would be a cook helping them, we created the good atmosphere. We convinced a lot of people – family, students, and a kiosk owner. So we created a kind of crossover inside. There was a ramp connecting the box with the bubble. And the ventilator continuously blew air inside of the bubble. This was very important to expose the system ‒ if you went inside, you could feel how it works.

We created these nice atmospheres. We travelled through the city for one month, to four different sites of Duisburg. Underneath the Highway Bridge we created incredibly nice neighbourhood banquets. It was also a crossover because of this festival; they had visitors, so neighbours, visitors of the art festival and artists, and ourselves came. It was a really successful thing, and it still exists, we still have this pavilion from 2006. This is now the 6th year. We’ve had a lot of requests and we’ve started to transform it.

Kitchen monument in Duisburg. Photo: Rainer Schlautmann, 2006

Kitchen monument in Duisburg. Photo: Rainer Schlautmann, 2006

This is another city, the park ‒ we transformed it into a ballroom and we organized dance evenings for teenagers but also in collaboration with elderly people. In Warsaw, in 2007, we cooperated with artists in Warsaw and we made a kind of conference about public space in the newly designed pedestrian zone ‒ how public space is used and how artists could act in a public space. What you see here it is not a high pressure system, it is very soft, it is melting with the city, it is very nice. The nicest moments are if it is connected to architecture or to nature.

We were invited by the biennale in Liverpool, and you can see how nice it is wrapping the trees and also lanterns. There was also a workshop with planners and neighbours about gentrification and the trading process in this neighbourhood. Also in Liverpool we organized a neighbourhood party inside the bubble, in the area which was planned to be totally demolished, but now it is partly demolished, it is still there, and we made a kind of party with all the kids and the people there.

Test of Sedia Veneziana. Photo: raumlaborberlin, 2010

Test of Sedia Veneziana. Photo: raumlaborberlin, 2010

In 2010, the most exciting moment for us was an invitation to the architectural biennale in Venice. The conference, called “Ecological urbanism”, was suddenly organized by Harvard ‒ all the important architects were sitting there discussing the issues of ecology and urbanism. We also did a programme, it was the quiz show we organised. We also organised a quiz show about the ecological urbanism, we called it the Green jeopardy. Do you know the 70’s show in Germany called the Big Price, don’t know if you had it here? This is the bridge to the next kind of work we did, this is a kind of chair we also built in Venice; this is the dream of the architect, deciding to build the chair, also our dream. This is the same chair, you can adjust it, you can see the low and high situation here, and you can turn it around. It was also the strategy we were working with, one of our practices is the instant building. We are not designing and building the chair, nor are the companies building the chairs and we sell it, no – we make it in a kind of collaborative process. We were invited to the Venice biennale, and we developed this chair called “Sedia Veneziana”. We are always looking for some hybrid functions; we wanted to use the chair as a building unit, to build mega structures. The idea was that we would go to Venice with the workshop and build these chairs during the exhibition, using the chairs as units to build architectural elements and structures. And this is how it looked at the end. We prepared everything – we prepared the kitchen, the workshop, the drills, screws, a big manual on the back, then it was easy for the people – you can just take the wood and screw it together in the way that it fits – very simple, like 10 minutes. This woman is building chair number 210, the little girl is building chair number 197, so people were very proud.

The chairs were not able to leave Italy or even Venice because they were very heavy. So what happened was they left the chairs everywhere, this is in front of the Italian pavilion. And the chairs created nice social spaces. They also went to the German pavilion, it was a great success. What was behind this idea? Everyone of you knows – if you are like 4 years old as a kid you start thinking about creating worlds – you take your mattresses and build tents out of them, or you take a blanket and put it all over the table and inside you have your own house, and if you look out you discover the world from the new perspective. And this is something that we are trying to keep and to bring to our projects. This is why we use the chairs to build something special or extra, like in our childhood. Like the wall where you could live in – this is one of three big structures we built with chairs in Venice. Or the tribune or mountain we built on the island between the Austrian and Greek pavilions which was free and the structure was used by a lot of people.

Sedia Veneziana in the mountains. Photo: raumlaborberlin, 2010

We talk about architecture as the key profession to manage urban transformation processes and raise new imaginations for urban futures. We do this without building houses, but by creating intermediate forms and formats. Our spaces are spaces of action and of negotiations, and are built on the belief that “space is a product of social (inter)action” (Henri Lefebvre). This is the most important quote for us.

Q from the audience: How many bubbles have you damaged? I think one bubble lives for about 15 events and then we have to build a new one. The kitchen monument travelled through a lot of countries in Europe, I think we have built 5 or 7 bubbles now, I don’t remember, because we continued experimenting with the system, we improved it. I think we have 5-6 different pavilions with bubbles running at the moment.

Q from the audience: Probably my question is premature, because I can see on the slide the topic you will talk, so maybe there will be the answer, but I just remember some actions and initiatives made by Nomeda and Gediminas Urbonas, the famous Lithuanian media artists, who were also attempting collaboration in public spaces. But the media they chose, the prime media was virtual media, television, free media and some other medias to create this social action and interaction, and this physical space was a little bit like a background of it. I wanted to ask how you feel from your own experience how those physical spaces, the forms of spaces, conditions that you made by pure physical architectural means, how do they make better conditions for the social interaction? We try to make it as simple as possible, and as nice as possible, and we try to connect to the conditions of the site, intensive research is the foundation of everything. You have to be simple at the beginning, because the knowledge about the media art or the computer is not as spread out as some people think. We like open spaces, we like to create free open spaces where people could plug in with their own ideas, start using that space for media art or something in this direction, this is perfect. But the space itself should be simple, and the invitation to the people should be… ah… it is more about hospitality, I think and if you are nice, people are also nice. So this is just an exchange, it is a one-to-one thing, and you have to find out what this could be. So if I continue maybe inside of the project there will be an answer, an additional answer to that question.

BangBang. Photo: raumlaborberlin, 2009

BangBang. Photo: raumlaborberlin, 2009

In 2010 we were invited to South Korea to participate in the Anyang Public Art Project, in Anyang, a neighbouring city of Seoul. The curator had a very experimental approach, the title was “New Communities in the Open City”. It was the third festival in a society where this kind of architecture is just growing incredibly fast and eating everything up, so they demolish every existing, they erase everything and they build a totally new structure. I think we all know and we have all learnt a little bit from the 60’s, but it didn’t apply to these countries because the technical, spatial quality was even worse than the concrete slab areas in the GDR or West Germany, or Russia. Somehow the big companies in Korea like Hyundai, Samsung, and LG have everything, they have electronic, but they also have building companies, do administration and all this kind of stuff. And they sell – they have these real estate companies as well, so they make a lot of money related to this. It is really fast, and in Korea a lot of people start thinking about it – they start losing their roots. They still have a very conservative and tradition behaviour towards each other, with the family, but they have to start living in a modernist way which they don’t understand and they lose their kind of individual spaces and their traditional routines.

Under this kind of tension – the curator, Kyong Park, invited 35 artists from all over the world to Korea to deal with it, and he also invited us. We were asked to build a kind of community centre inside the park. Two other architectural offices LOT-EK from New York and MASS STUDIES from Seoul were also asked to build a structure there to be able to show all these synergies. When community artists organize workshops with children, they don’t have a spectacular monument later which is there forever, like Dan Graham is doing or Richard Serra. They create a process and they start to develop ideas but it’s not really visible, so we had the idea to have a park in the centre, a space in the centre with different institutions which make all these energies growing inside of the urban reality visible. We used part of the older building structure from the 70’s and used the roofs as gardens.

BangBang. Photo: raumlaborberlin, 2009

It was my first time in Asia and Korea and I felt like an alien, so it was just a big challenge for an alien to deal with the community in their foreign planet. We started to connect, meet people, to be on site, and to feel this kind of structure, culture and the atmosphere of the space. And we were also asked to build a tool, a very ancient kind of Kitchen monument called Bang Bang ‒ bang means space in Korean. It has a very important traditional meaning, and we used this word – space meaning the multifunctional space, with the idea of being extendible to different sides, like a Swiss knife you can combine different extensions just for the needs that you have. We built this in 2009, as a tool for the festival ‒ for the artistic director, for the city hall, for the artists to be able to be mobile to start finding connections with the society. In the beginning we started conducting research by ourselves, a subjective research, we made workshops together with high school kids, we mapped old neighbourhoods, and they also made the designs and desires as to what they like. For us this was a very important process to understand the problems, potentials and desires, and also the contrast, frictions and tensions inside this society, especially between these big buildings, this homogenized society and the tradition of this individual informal acting with each other.

Urban Detective. Photo: raumlaborberlin, 2009

Urban Detective. Photo: raumlaborberlin, 2009

And so we mapped it, we made 4 huge maps, for example, the potential map. One map was exhibited in the park later as a huge 3 x 4 metre billboard. We also had a desire map which was a section through the city with interviews and drawings, 7 metres long and 1 metre high, and we used all our experience to make the design of a vertical village. We wanted to use this global format of the high-rise and combine it with the desire to have the individual houses and units and also spaces to act; along with farming ‒ it was also a community farm.

Mobile planting. Photo: raumlaborberlin, 2010

Seventy percent of this urban society comes from the countryside and they have just the part of development that we in Europe had 150 years ago, when the industrialization, urbanization effect came. There is a big desire to plant and to have areas for farming, but this is not about planting nice flowers, it is for planting and growing salad, cabbage and this kind of thing. We started discussing this idea, and the question of how to connect people with the idea of architecture. The first thing we did was to ask what kind of material you need in order to build. We also wanted to have a farm or a garden, a public farm-garden, so we also needed plants. We went to the neighbourhoods and we asked people, families and children to plant their plants in some pots we had organized and label it with their name, and we brought these plants to the first building units of the vertical village. It was just a park and the plants. The plants were meant to be brought to the vertical village but it was not there at that time.

Then as a strategy of the instant building practice we invited citizens to build the vertical village with us. We opened this building workshop in the park in the summer for 7 weeks. It was about planning and building. Planning means thinking about individual houses or what structure could be used, what functions they could have, what kind of furniture we need, or extra infrastructure, etc. In the end we built with more than 200 people from the neighbourhood. Teenagers, children, families; it was a simple structure – frames covered with wooden panels, flexible, every house was 2.5m x 2.5m, very simple. There was an unemployed carpenter from the neighbourhood, he worked all 7 weeks with us. Children came and used the leftovers for their toys, and they also decided that this vertical village needed a children’s house, so they built toys for it. We needed a guiding system to let people know what happens. We found a chair on the street and we started planning with the children, inventing a children’s chair Anyang style, and we starting building it. After the village was finished we opened it with a programme.

Map of Open House. raumlaborberlin, 2010

The first house we built was the bar, which we built by ourselves. It was also very important to connect the people with this site, so the second house was the planning office, and then a tea house. The housewives, they call them jubu – are real housewives – the men work and they are at home, they take care of things, and they have the power. You have to convince them; if they are against you – you cannot work in this field at all. But they are also very active, singing together, dancing together, so we offered them the potential of this open house. In the end we built 20 houses, and we also needed the structure to set up the houses in a vertical way. There were 5m x 5m platforms on the steel structure. There were different heights and levels, and we had a central stairway in the middle with the tower and two additional entrances on two sides. The ladder is a shortcut to the farmer’s office. Parallel to the workshop with the wooden houses there was a company building the steel structure, just next to us. After everything was done there was a big event, a train came and lifted all the houses on the structure. And on the 3rd October 2010 it was opened.

Collage street side of Open House. raumlaborberlin, 2010

Collage street side of Open House. raumlaborberlin, 2010

Here in the park is also the white pavilion built by MASS STUDIES, which was more an open space, and the container was built by LOT-EK from New York called Open School where we had our office, made our workshops and also had an exhibition. This is the community centre open house on the right. The square where people are dancing was a former workshop place. It is lifted up ‒ this was the design of the platforms that came out of the landscape and the park design. We wanted to have it very open, a kind of monolith monumental architecture, but a rather fragmental structure that is growing like a plant. There was a festival in which some artists used the pavilions for their works. As you can see with the frames we could also work with materials, to create different kinds of surfaces for the pavilions ‒ we used caravan windows as windows. And here children started to appropriate the spaces. All the chairs and tables, greenhouse with the plants inside – all the things we built with the people. There was a farmer, an unemployed taxi driver, who used to be a farmer and started to work there. Also the unemployed carpenter asked if he could have a workshop, and in exchange he could be the housekeeper dealing with the pieces that were run down. And it’s still there, it is still in use. It is used differently than we expected, because it is free, they can do whatever they want with it but they still love it.

Open House. Photo: APAP, 2010

Open House. Photo: APAP, 2010

Q from the audience: Did it have the political impact or the social reaction on the skyscrapers building? In the city they stopped building skyscrapers after the festival. We were not expecting this, as we were still thinking about it ‒ is it because of the festival? But they stopped because they only had a few parts left and they started to understand that diversity is a quality. How it is used today? I am sorry but it is too far away. In the next project I will show you I have more contact, I am still part of what happens there, but this is too far away, sometimes people send me an image on Facebook. They used it for two times as an exhibition space for local artists and it is mostly used by the children as a playground, and the families love it. I don’t think it is a farm anymore. But the problem is that when we left the city closed the entrances and said it will have opening times, because they were afraid to have the an open structure without being able to care for it. They also installed surveillance cameras. You know it is slow, slow… you cannot expect that things will change the world from one to the other. It is just a process that is growing and if they stopped building high-rise buildings – then it is a success! But bringing people together… The park between the high-rise area and the low-rise, it’s also the psychological thing that people are not connected to each other anymore. Urban structures are separating society and for us this house was like a bridge. We did not want to propose or to say it was better, no, we wanted to build a space where people could meet and talk about how they would like to live.

Eichbaumoper. Photo: Rainer Schlautmann, 2009

Eichbaumoper. Photo: Rainer Schlautmann, 2009

The final project I will show you is again an industrial region in West Germany. This is the highway built in the 60-70’s. It is one of the most used highways in Germany, with more than 120,000 cars per day. There is a highway intersection with a metro station in the middle. This metro station is part of the vision which was developed in the 60’s, when the coal mines and steel plants started collapsing. And they thought ok, we want to connect the region of the 53 cites with a huge traffic infrastructure system like a metro system. And what they did was the line between the cities of Essen and Mülheim. This was because of money; they built it on the middle stripe of the highway – not underground. Nowadays it is really horrible – it is cutting the urban landscape in two parts, going through the inner cities, it is very dense; being on this highway on a platform over ground and waiting for your metro is just horrible. The station also has problems of how to connect the both sides ‒ it is necessary, because these sides are separated from each other, you have only a few tunnels every 1.5 kilometres you can go through. And this is the situation, people are really afraid ‒ it is one of the typical urban fear spaces. The planners reacted with a fence – they thought if they built a fence people would feel safer, but if you see the fence you are more afraid than before… The whole thing is a very ugly unused space.

Eichbaum. Photo: raumlaborberlin, 2009

Eichbaum. Photo: raumlaborberlin, 2009

When we discovered this in 2006, it was also the time of the Kitchenmonument, we also found out that the space had been totally given up on by the metro company, planners, and people; nobody knew what we could do. We don’t believe that you cannot do anything anymore; that you have to live with this shit ‒ we also realized that we had to be very radical ‒ insane ‒ in this situation. We are always looking for ideas from history or the past. We found this wonderful movie called Fritzcarraldo by Werner Herzog, where Klaus Kinski as Baron Fritzcarraldo has an idea to build an opera house inside the Brazilian jungle, but to finance it he has to open a trading line on the river but to be able to do this he has to carry a ship all over the mountain. And this is something that we thought – it is so complicated that we also need an idea like this, so we developed a kind of vision to transform the space into an opera house. The name of the place is Eichbaum, very romantic, it means oak tree – there was a big oak tree next to the house which was the restaurant, it was kind of a community place. Everything was erased with the construction of the highway and the metro, but the name remained. We thought ok, let’s do an experiment on how we could deal with the community because this was top-down planning. Transforming the opera house was our idea ‒ we thought it would be a place of hope, because they wanted to develop the system, to find new jobs for the people.

We invented this ephemeral space and we invited people from the neighbourhood, a composer, musicians and started conducting the first experiments. It was really very successful, so we continued. We started to find partners – we found in the region two big theatres from the cities and one opera house of Gelsenkirchen and we started to develop it, we made applications for the foundations because we needed money for this. We found all the money and continued developing the idea of being there. We had an idea to build a building shelter like in the Medieval ages when the specialists, architects and handcrafts came together to discuss new constructions and to build wonderful cathedrals. We thought that in our time we need a space where specialists like composers, conductors, opera singers and citizens can meet together to develop this opera. We built it from containers as an iconic building, a symbol of transformation, and we renamed the station.

Eichbaumoper. Photo: raumlaborberlin, 2009

Eichbaumoper. Photo: raumlaborberlin, 2009

The renaming of the station was really interesting because we found out there were hidden users – they were teenagers who just hung around. Eichbaumer means a person from Eichbaum, so it was the kind of identification process we liked – we started playing this game, and we started inviting people to work with us. We invited the composers, a composer from Munich, a composer from Belgrade and one from New York ‒ different foreigners worked with people and not only with people – with the atmosphere of this station, with the noise. It is a highway; you can always hear the cars and the metro. We didn’t want to stop the metro; we didn’t want to fence the space, being in the opera house they should melt together ‒ the public space and the idea of the opera. And we did not want to bring an existing opera to the place, we wanted to create everything out of the conditions of the site. Opera singers from the Opera house also started experiments, they were exposed, and it was a big challenge for both sides – for the citizens, for the reality and also for the people who are normally working in the black boxes. After almost one year of work on site, we had transformed it in a very nice architectural way using the whole space, there was kind of over-layering fiction and reality.

General rehearsal at Eichbaumoper. Photo: raumlaborberlin, 2009

General rehearsal at Eichbaumoper. Photo: raumlaborberlin, 2009

The start was when the part of the opera was inside of the metro in the summer of 2009. The residents are the real experts of Eichbaum opera. All the librettos include stories told by the residents, some of the stories were incorporated directly into the text. The residents themselves became the authors. Tales of daily lives transformed into song, many of the stories tell about work, poverty and loss. One aria tells the story of a mother who was pushed to give up her child. Sixty local residents played in the production as extras. Adelheid Höning has lived in the area since 1926, and until recently she avoided the station. Cerdula Daupner is a director, she is in charge of taking the residents stories and bringing them to the stage: “It feels like we are creating something a little bit like an oasis here. The place where the people feel their stories are told and appreciated. Where they can feel that what we are creating here is about their own lives. It’s meaningful to us”. The sounds and rhythms of the subway play their own role. While subway traffic continues in the background actors play emotional scenes on stage. An unusual production at an unusual location, and the new beginning of the Eichbaum underground station.

What happens after this mega event and spectacle? For us it was really important to continue working with the effects. The most interesting effect was the contact with the teenagers. They complained in the beginning – why opera, why not hip-hop style, but then they were really proud. We continued for another year, we got more funding and we developed different things with the teenagers – workshops. The relief in the back is something that we did together with the teenagers, developing the relief and also building it.

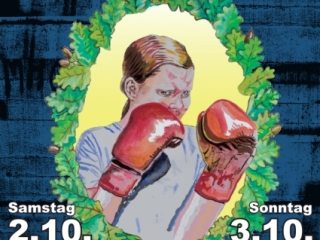

Eichbaumboxer poster. raumlaborberlin, 2009

We organized another event – we transformed it into a boxing arena, because there were many Polish teenagers there and it was a problematic thing because on one side are the Polish people – teenagers and their families, on the other the Russian, Turkish and the Germans, so this was also a place of conflict. The Polish were engaged into the local boxing club, so in collaboration with the boxing club we started to work on that project on different levels. We created posters, the drawings were made by the teenagers – they did the photo shoot and made the posters. One year later there was a boxing championship. A lot of clubs from the cities of the whole region came and made a real competition here. The opera transformed into the boxing arena ‒ with a real ring, real referees, real points, and different weight classes – it was absolutely cool. We called it “Fighting with Fists and Words” and we combined it with rap battles outside.

Eichbaumboxer. Photo: raumlaborberlin, 2009

Eichbaumboxer. Photo: raumlaborberlin, 2009

Going back to the question of the beginning now – how sustainable is a temporary? This is a question we are asking ourselves “How we can establish these effects of the one-to-one activations, of these experiences, how could this be the procedural way of transformation to make spaces like this better places for us and with the potential to use it?” We continued working and at the moment we have developed a vision for this, which is called Eichbaumpark. We got paid by the city of Mülheim, it is kind of master plan. But we don’t like master plans because they force one to develop things for the next 20 years and no one knows what will happen tomorrow. If the economy collapses, you can throw away all the masters plans.

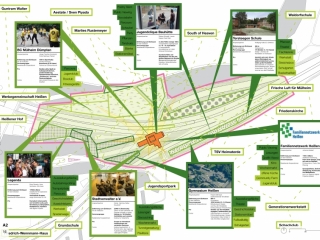

Partners for EichbaumPark. raumlaborberlin, 2011

Partners for EichbaumPark. raumlaborberlin, 2011

We think in a more flexible way, we call it a dynamic master plan. The idea is using the area, desires and wishes that people have, and what they miss in the neighbourhoods. All the networks we created with regions and networks from all over the world, also the knowledge which grew up there – this is a kind of patchwork of different fields which you can develop in different time frames. They have some topics like parks and gardens or farms or sports. It does not have to be finished in two days, it is just a way, maybe it will need 50 years, you never know, as it also depends on how you will use the potentials and the money. For example, the metro company invests money every year to get rid of graffiti, they paint everything white and it costs 20,000 euros, and one day it is full of graffiti again. So at the moment we are dealing with them that we can just make the next big thing be a big graffiti workshop inviting international graffiti artists with the local scene painting the whole area for this money, the whole metro station. The Highway Company pays a lot of money for the edges of the highway, cutting the plants – maybe we could make the design and they could work in a direction which could be good for this development. These are only a few examples of what we expect. We have developed a lot of tools, ideas and hopefully we will be able to continue, and these containers are still there, ready to be used by neighbours, they make coffee afternoons showing the new hats, and the teenagers put on concerts, local artists have exhibitions. So we can keep this energy, and the space that nobody wanted to be in is now a space of potential where everybody can imagine making something nice.

We come to the end, because it is all about the process of the architecture, architecture as a process, so the summary from my side is: “Process based architecture from mutating cities is situative, local, playful, open, cooperative, confrontational, international, humorous and adaptive”. No Trust ‒ no City. Thank you very much.