- INTRODUCTION

- LECTURES

- Miles Glendinning / The Hundred Years War: a ‘Long Century’ of Mass-Housing Campaigns Across the World

- Auguste Van Oppen and Marc Van Asseldonk / Open-Source Urbanism

- Tim Rienets / Less Is More? Urban Design and the Challenge of Shrinking Cities

- Adam Bobbette and Etienne Turpin / Aberrant Architecture: Typologies of Practice

- Matthias Rick / Fleeting Architecture ‒ Raumlabor’s Instant Urbanism

- ESSAYS

- Nerijus Milerius / Breaking Point: from Soviet to Post-Soviet City

- Benjamin Cope / A Reflection on Breaking Points in the Case of The Praga District of Warsaw

- Miodrag Kuč / Berlin. Becoming Normal?

- Mindaugas Pakalnis / Vilnius. The Challenge of Disintegration

- Siarhei Liubimau / Popular Urbanism and the Issue of Egalitarianism

- INTERVIEWS

- No Trust – No City / Matthias Rick Interviewed by Ona Lozuraitytė and Aistė Galaunytė

- The Man, Who Turned the Barbeque into the Center of the World / Benjamin Foerster-Baldenius

- Radicalising the Local / Jeanne Van Heeswijk Interviewed by Kotryna Valiukevičiūtė

- Learning-By-Doing / Laura Panait Interviewed by Arnoldas Stramskas

- Preserving the Generic / Kuba Snopek interviewed by Marija Drėmaitė

- A Permanent Anticipation of Uncertainty / Adam Bobbette interviewed by Arnoldas Stramskas

‘The world has entered the urban millennium,’ former UN General Secretary Kofi Annan declared in 2001, referring to the rapid growth of the world’s urban population. Since then, the news has spread among the public and experts alike that from now on, the majority of the world’s people will be city dwellers. And, as you may have noticed, since this statistic was published some years ago, most books and most conferences on global urban phenomena are in fact using this quote to provide the own work with extra emphasis. And so do I this evening…

It is a demographic milestone of truly historic significance, and the statistics are unmistakable; in this millennium urban spaces will become the predominant human habitat on Earth. More people will live in cities, and an ever-growing surface of the planet will be covered by urban spaces causing unprecedented challenges in many urban areas such as shortages of housing and social services, depletion of basic resources, economic woes, environmental problems, and ‒ as a result ‒ social tensions and conflicts.

However, I want to use the quote of the ‘urban millennium’ to make another argument. I want to point out that not all cities are part of this process of vast urban growth. Rather the opposite; the advent of the ‘urban millennium’ is paralleled by a reverse demographic trend: for the first time in history, countries are leaving behind the centuries-long period of population growth and entering a phase of prolonged population reduction.

Shrinking countries by 2050. Shrinking Cities / Projektbüro Philipp Oswalt

Shrinking countries by 2050. Shrinking Cities / Projektbüro Philipp Oswalt

This process is without historical precedent too, and will confront the cities that are affected with new challenges as well. These cities, which are losing population against the prevailing trend of urban growth, are confronting us with different kinds of problems and dynamics. These problems might be less urgent than those caused by uncontrolled growth; however, we know even less about them or about possible solutions. For this reason, I want to use this lecture to throw some light on a part of urban history which, until recently, had almost gone ignored, had been forgotten, or considered taboo. A part of urban development, however, that will be of increasing relevance in the 21st century in many regions of the world.

Shrinking cities are by no means a new phenomenon; the loss of population has been as much a part of urban history as growth. The Bible tells us about cities which have been abandoned, destroyed or punished by God. Just think of Sodom and Gomorrah, or of the tower of Babel. And if we investigate other historic sources, we can find numerous other examples. Cities that have been destroyed or fallen victim to fire or natural catastrophes. Cities which have lost their political or economic significance and cities which have been devastated by the Black Death or other epidemics. All these historic cases have one thing in common: they were perceived as catastrophic events of truly existential dimensions, threatening the existence of people, gods and heritage.

Historical examples of shrinking cities. Shrinking Cities / Projektbüro Philipp Oswalt

Historical examples of shrinking cities. Shrinking Cities / Projektbüro Philipp Oswalt

However, since industrialization triggered an accelerated expansion of cities about 200 years ago, we have almost forgotten about shrinking cities. And today, after 200 years of almost continuous urban growth, it is difficult for us to consider shrinking cities as something normal. Instead, we tend to consider it as a deviation from the norm – as a deviation from the normality of continuous growth.

I will take you on a quick time travel – a time travel into the history of shrinking cities. And during this travel I will highlight some of the main reasons for shrinking cities and I will take you to some places which have played a paradigmatic role in the history of shrinking cities. I will focus in particular on the old industrial countries in the 20th century, where urban shrinkage for the first time turned from a timely and geographically limited phenomenon into a widespread and long-term process.

But beside all the details I have some main arguments which I will tell you in advance. A central argument of this lecture is that industrialization did not only cause the ubiquitous economic and demographic growth, as is usually believed. This is just half the truth, because industrialization also enabled developments that worked against the tendencies of growth. I will give you some examples: Cities have suffered from violent destruction made possible by the mechanization and industrialization of war. Cities have experienced waves of out-migration made possible by means of modern transportation techniques. And many cities have experienced unprecedented economic crises, which hit the industrial sector and caused unemployment and deindustrialization. Moreover, the wealth generated through industrialization can be closely linked to demographic processes, such as low birth rates and the aging of populations. Hence, industrialization has not only caused rapid urban growth, at the same time it has contributed to the process of urban shrinking in many ways.

The close relation between shrinking cities and industrialization can accurately be retraced if the historic and geographic developments of growing and shrinking cities are compared. Obviously, the increase and distribution of shrinking cities in the 20th century has followed the same geographic route as that which the growing industrial cities had taken decades before.

The rise of shrinking cities started exactly where the accelerated growth of industrializing cities had its point of departure. The first concentrations of shrinking cities appeared in Central European countries and spread according to the geographic pattern of industrial urbanization. Manchester, known as the first industrial city in the world, was one of the first large cities to experience population loss over the decades to come. Other industrial cities and regions in Europe and the United States followed.

Growing and shrinking cities. Shrinking Cities / Projektbüro Philipp Oswalt

Growing and shrinking cities. Shrinking Cities / Projektbüro Philipp Oswalt

However, as simple as this picture may be, as manifold are the causes and features of shrinking cities. Moreover – and this is another argument I want to make in this lecture – the shrinkage of cities is not just a demographic process that can be quantified by statistics. The shrinkage of cities also means qualitative changes, which cannot be said to follow a basic homogenous pattern. The shrinkage of cities is not only a demographic phenomenon, it rather touches all aspects of urban life and urban development: economic, social as well as cultural aspects. And last but not least, the shrinkage of cities also affects our own profession, because under conditions of urban decline, architecture and urban planning suddenly finds itself confronted with entirely different tasks and possibilities.

This doesn’t mean that we have to forget the methods and instruments we have developed in recent decades. Yet, I am convinced that we need to develop new methods and instruments suitable for the requirements of shrinking cities. We have to invent a new image ‒ a vision of future cities, and we even have to rethink our self-understanding as architects and planners.

All these methods, images and self-perceptions that we are used to, can only be understood in the context of industrial growth. In contrast to older forms of urban planning, which were mainly aimed at military defence, control and representation, the industrial age demanded something else. The industrial age demanded technical solutions to facilitate industrialization and to solve the immense problems it caused. This urgent need gave birth to modern urban planning as we know it today. In short, from an urban planning point of view, urban growth of that time was perceived as a crisis. It was widely identified as the main reason for many of the unbearable conditions in industrial metropolises. Consequently, many planners and theorists of that time period conceived shrinkage as a reasonable strategy to overcome these crises. From this perspective, decentralization, low density, and even shrinkage were not perceived as problems. Rather the opposite, they were widely perceived as desirable alternatives and inspired various urban visions, some of which influenced urban planning for decades to come.

One of the most famous examples is Ebenezer Howard’s concept of the Garden City. It was not just meant to represent a healthy, scenic and semi-rural antipode to the industrial metropolis. Beyond this, Howard wanted his Garden Cities to operate like magnets which – I quote – ‘will produce the effect for which we are all striving ‒ the spontaneous movement of the people from our crowded cities to the bosom of our kindly mother earth.’ And what is less known is that Howard even recommended shrinking London to a mere twenty percent of its population at the time.

Planners in America also developed low-density and decentralization ideas, the most famous of which was Frank Lloyd Wright’s Broadacre City. In his book Disappearing City, he demonized the industrial metropolis as unhealthy, inhuman and corrupt. Against this dystopian background, he promoted the extremely low density of Broadacre City to reverse the failures of urban centralization.

In the course of the 20th century, architects and planners developed numerous other ideas to overcome the problems of fast urbanization. Think of the Russian deurbanists who wanted to rebuild all urban settlements along main traffic infrastructures. Or think of the British architectural group Archigram who invented moving cities. What all these visions ‒ and many others ‒ had in common was that ideas of shrinkage were perceived as controllable developments based on technological progress and opposed to the undesired, disorderly, and failed urbanization of the early industrial metropolises.

Or to put it in simple terms, the technical and economic resources, which had been generated and accumulated within the industrial cities, had to be invested in large-scale utopian projects in order to overcome and dissolve the same industrial cities. In fact, the industrial city with all its problems gave birth to an anti-urban discourse among planners. A discourse which had its point of departure in the 19th century, when socialist reformers and conservative thinkers invented their counter cultural communities, most of which were located outside the city.

Today, large and growing cities are once again the subject of anti-urban discourses. On one hand, there is the discourse on uncontrolled urban growth, especially in the global South. This urban growth is widely perceived as a breeding ground for health problems, social decline, crime and violence. And on the other hand, there is the discourse on sustainable development, which portrays cities – especially the vast and energy thirsty metropolises of the developed world – as major polluters who are damaging and destroying the world climate and natural resources. Again, in both cases size and density and growth of cities are identified as critical parameters.

Economic crises

The early visions of low density and shrinkage never came true. However, at the same time, an increasing number of big cities experienced an unexpected and unplanned loss of population. At the beginning of the 20th century, severe economic crises and supply problems on a national and international level interrupted urban growth in many places. Food supply problems in the wake of the October Revolution – for example – literally drained Russian cities. Millions of urban residents fled to the countryside in order to survive by means of subsistence farming.

Later, the Great Depression in the 1930s also led to temporary urban-rural migration. Urban population loss was less dramatic than in Russia, but nevertheless led to a decline in urban growth rates in all industrialized countries and the shrinking of many cities. Again, people left their cities in favour of rural living conditions or informal settlements where they could self-sufficiently meet their basic needs. This unexpected trend towards interim relocation to rural areas was willingly accepted by many politicians and planners who promoted anti-urban thinking. Modernist and socialist-oriented planners perceived the informal semi-rural settlements as a new symbiosis between city and countryside, whereas conservative planners saw these settlements as a return to an agricultural lifestyle.

In recent years, the world economy again found itself facing major crises. So far, besides numerous projects and construction sites being on hold, the impact of these crises became obvious in the form of the so-called ‘Foreclosure Crises’ in the United States. Suburban areas in which entire neighbourhoods were built on the sandy grounds of uncontrolled speculation have been vacated, literally turning into ghost towns.

Unlike the major economic crisis in the first third of the 20th century, which caused spontaneous out-migration from cities in favour of rural and semi-rural areas, the recent situation seems to be generating a contrary trend. The housing market in the United States and other countries exhibits noticeable signs of the spatial reorganization of suburban areas and a new trend toward more central ones. I will get back to this trend later.

War

Let’s get back to our historic review and focus on another factor which has contributed to the unprecedented increase in shrinking cities in the 20th century: the mechanization and industrialization of warfare. The destructive power of weapons technology developed and mass produced in the previous century, destroyed more lives and cities than ever before.

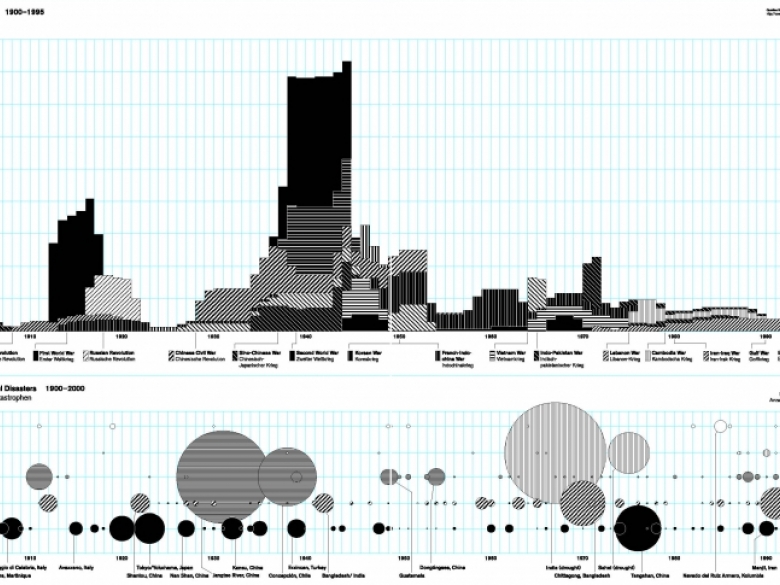

Wars and violent conflicts: Death toll, 1900–2000. Shrinking Cities / Projektbüro Philipp Oswalt

Wars and violent conflicts: Death toll, 1900–2000. Shrinking Cities / Projektbüro Philipp Oswalt

The full potential of modern warfare for destruction and killing was demonstrated in the bombings of cities such as Rotterdam, Coventry, Stalingrad, Hamburg, Tokyo, Dresden, Danzig, and many more in World War II. Here, the targets were not only industrial plants, military facilities, and other neuralgic points of military relevance. Especially German and British Forces targeted civic urban structures in order to demoralize the people and to weaken military and political determination. Finally, the immense destruction of World War II culminated in atomic bombs being dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki. In Hiroshima, one single bomb was enough to destroy two-thirds of the city in one blow ‒ human beings and structures alike.

After World War II, again many concepts for reconstruction were fuelled by the old ideas of decentralization and low density. Many urban planners saw the devastation caused by the war not so much as a loss, but rather as an opportunity to build modern cities and to overcome the insufficient living conditions of pre-war times. In a large number of plans ‒ both realized or not ‒ ideas of low density and a limited number of inhabitants were a central concern.

War and armed conflicts, 1945–2001. Shrinking Cities / Projektbüro Philipp Oswalt

War and armed conflicts, 1945–2001. Shrinking Cities / Projektbüro Philipp Oswalt

Although threats of mass destruction still exist and have even expanded, new forms of violence and destruction have emerged in the wake of the geopolitical changes caused by the collapse of the Soviet Union and the rise of international terrorism, threatening an increasing number of cities today. Since the rise of modern nation states we were used to wars being fought out outside the city gates, one national army against another. But for some years now, this convention of warfare has been obsolete. Most violent conflicts today are fought out between national armies and informal combatants and at the same time a growing number of these asymmetrical conflicts are taking place in urban environments.

In some cases, such as in the former Yugoslavia, Iraq, or the Caucasus, cities have become the centres of ethnic and nationalist violence. Here, multi-ethnic populations, which had coexisted for decades under the control of authoritarian regimes, suddenly found themselves on the front lines of violent conflicts. Buildings and public spaces were targeted as national and ethnic symbols, and – as I want to argue – also as symbols of urbanity as such.

Suburbanization

Although the mechanization and industrialization of warfare destroyed more lives and cities than ever before, it did not stop the general tendency of urban growth. Most cities affected by military destruction recovered and in most cases even exceeded pre-war population. However, just those regions, which have entered a long period of peace and welfare after World War II – I am talking about the so-called developed countries of the Western World ‒ experienced an unprecedented increase of shrinking cities. Whereas in previous times, urban population losses used to be singular events, restricted to certain places or regions and to certain historic time periods, in the second half of the 20th century, shrinking cities turned into a widespread and long-term phenomenon.

Periods of shrinkage, 1900–2000. Shrinking Cities / Projektbüro Philipp Oswalt

Periods of shrinkage, 1900–2000. Shrinking Cities / Projektbüro Philipp Oswalt

Right after the War the number of shrinking cities in Western industrial countries rose to approximately one hundred, then grew to over 200 in the 1970s and reached a peak of more than 250 in the 1980s. Not only did the number of shrinking cities rise substantially, according to census data, also the average population losses increased and the average duration of this process became more prolonged.

We can identify two main reasons for this significant and persistent increase of shrinking cities after World War II. Firstly, the once-booming industrial centres suffered an ongoing loss of economic competitiveness, declining labour markets and, consequently, population increase. Secondly, in many regions, the process of urbanization passed into a process of suburbanization, meaning that economic and demographic growth increasingly accumulated outside the urban centres. Residential developments and other urban facilities, such as retail, leisure, and industry, sprawled into the hinterlands and, in many cases, drained the economic, fiscal, and demographic resources of the inner cities.

This process of suburbanization became a central feature of urban development in almost all Western industrialized countries and a major reason for an increase of inner city population losses, especially in the United States. During the 1950s, more than eighty US cities were shrinking, including the twelve largest cities in the country (with the exception of Los Angeles). This rapid transformation was triggered by a combination of different factors. Firstly, the growth of the middle class and their ability to afford cars and single-family homes, the availability of low-interest loans, the extension of highway networks and also the decentralization of employment and consumption facilities.

Combined with a tendency toward ethnic segregation, these factors led to a mass exodus of the mainly white middle classes from city centres, with enormous social, demographic, and economic consequences, especially in the north-eastern United States. Over the years, some major cities like Detroit, Pittsburgh, St Louis or Buffalo lost about half their populations. What used to be bustling city centres were left behind ‒ ruined, half empty and socially deprived. Detroit, for example, shrank from almost two million inhabitants in 1950 to less than one million in the year 2000. The suburban districts around Detroit, however, almost tripled from 1.2 million to more than three million in the same time period.

Population development. Detroit and subburbs, 1900–2000. Shrinking Cities / Projektbüro Philipp Oswalt

Population development. Detroit and subburbs, 1900–2000. Shrinking Cities / Projektbüro Philipp Oswalt

Deindustrialization

The second reason I mentioned which caused wide spread and long term population losses in industrial countries was and still is the process of deindustrialization. In this case, industrialization did provide the background against which negative demographic trends could unfold. Here, the industry itself was the subject of decline. Especially the old industrial regions that had experienced waves of intense growth in the 19th and early 20th centuries now suffered from the exhaustion of natural resources, outdated means of production, and increasing competition, while new high-technology manufacturing industries and advanced service industries have grown in different regions, competing for skilled labour. Detroit and the so-called Rustbelt is one of these regions; also the British Midlands, where industrialization started is among those regions; as well as the Ruhr and Saar region in Germany, the Po valley in Italy or the Donezk Basin in Ukraine.

Industrial cities and regions. Shrinking Cities / Projektbüro Philipp Oswalt

Industrial cities and regions. Shrinking Cities / Projektbüro Philipp Oswalt

Most of the old industrial cities were not able to offset the loss of economic power resulting from deindustrialization and to compensate the declining industrial sector effectively with new tertiary industries. Manchester, which has suffered from deindustrialization and suburbanization for decades, is one of a handful of industrial cities that has managed to establish a prosperous tertiary sector and to generate new economic and demographic growth.

Manchester brownfields, 2000. Shrinking Cities / Projektbüro Philipp Oswalt

Manchester brownfields, 2000. Shrinking Cities / Projektbüro Philipp Oswalt

Return to the city centres: Urban Renaissance

And there is another phenomenon which had its point of departure in the British Midlands. For the first time, planners and decision makers recognized urban shrinkage as a problem, and not the growth of cities. For the first time, urban planning wanted to work against urban shrinkage. Hence, a new urban policy was developed, which became known under the somewhat glamorous term ‘urban renaissance’. The goal was to refurbish the abandoned city centre and lure young and skilled inhabitants who would otherwise cross the city boundaries to live in the suburbs.

But it was not only planners and politicians who gave birth to the so-called urban renaissance. At the same time young architects and entrepreneurs had discovered abandoned industrial buildings and old working class districts to start their enterprises, to give space to cultural activities, and to live alternative lifestyles. The architectural office Urban Splash was one of these entrepreneurs who started their careers by refurbishing old industrial buildings and turning them into modern lofts and studios – a strategy which is common today, but used to be very progressive at that time. Today, there are no industrial regions which have missed the opportunity to convert old industrial buildings into museums, brain parks and creative clusters.

Regarding the needs of shrinking cities, the advantage of these projects is not so much the architectural quality. It is rather a strategic notion. The notion to invest a minimum of financial resources and a maximum of creative and entrepreneurial resources in order to generate new urban values in a seemingly run down environment. This kind of creative strategic thinking became crucial in other regions with declining urban populations, too.

Post-Socialist conditions

While the number of shrinking cities in Western industrial countries decreased slightly in the 1990s, the dramatic political and economic transformations in the Eastern European countries caused serious urban crises. The collapse of the Soviet Union and the Eastern European planned economies triggered unprecedented demographic developments: within a few years numerous cities fell into a state of political, economic, and demographic instability and experienced rapid population decline.

According to official statistics of the Soviet times, only 27 large cities of all Soviet countries lost population in the 1980s. In the 1990s it was 216 large cities, which means that one out of two cities lost population. Just in Russia, the number of shrinking cities grew from seven to more than ninety. Here, as in other ex-Soviet countries, the collapse of the political system hit the cities so hard that since then, more cities have shrunk than grown, and the urban population of Eastern Europe was in an overall state of decline. After 2000, the downturn came to a halt but shrinking cities were still prevailing and declining faster on average than national populations.

Number of shrinking cities: OECD countries (high income) and post socialist countries. Shrinking Cities / Projektbüro Philipp Oswalt

Number of shrinking cities: OECD countries (high income) and post socialist countries. Shrinking Cities / Projektbüro Philipp Oswalt

The disintegration of the Soviet Union impacted urban populations in many ways, including all the demographic processes I have mentioned: processes of deindustrialization, which used to be obviated by means of the socialist planned economy, suddenly hit industrial regions with full force, especially those where old and formerly protected industries were exposed to the competitive world market, for example the Donezk Basin in Ukraine or the Kusbass in western Siberia. The economic woes and existential fear triggered waves of out-migration and falling birth rates. In addition, the worsening of the quality of life for the majority of the population caused by decaying public healthcare, physical stress, and psychological anxiety, resulted in an alarming decrease in life expectancy. As a result, in 1993 the average lifespan of Russian males was three years shorter than that in the previous year, and reached a low mark of under fifty-nine.

Life expectancy and birth rates in post socialist countries. Shrinking Cities / Projektbüro Philipp Oswalt

Life expectancy and birth rates in post socialist countries. Shrinking Cities / Projektbüro Philipp Oswalt

Eastern Germany is also one of those regions that experienced a severe urban crisis in the 1990s as a result of political and economic change. Rapid deindustrialization, migration to western Germany, and falling birth rates have since caused urban populations throughout eastern Germany to decrease, with some towns having suffered population losses of up to 30% over a 10-year period. But unlike other regions which experienced sudden urban population loss in the wake of the collapse of the Soviet Union the crisis of eastern German cities clashed with the expectations and standards of an advanced capitalist welfare state established in West Germany. It is no accident though that nowhere else did the challenge of shrinking cities gain so much attention and produced so much innovation than in Germany.

Architects, planners, and scholars finally realized the far-reaching implications of the situation and the need to find solutions for a hitherto unknown problem. Architects and planners were being faced with an entirely new task for which nothing in their previous experience had prepared them for: Instead of designing new buildings, old buildings had to be deconstructed, dismantled, or converted; instead of designing new infrastructures, old infrastructures had to be reduced, reorganized, and adapted to less intense use; instead of designing new buildings to host programmes, new programmes had to be invented for existing buildings; and instead of being able to invest the financial surplus of economic prosperity into the urban environment, the losses and disadvantages had to be shaped and controlled in the public interest.

Shrinking cities tomorrow

At the turn of the millennium, inner cities were losing population in unprecedented numbers. Over one in four inner cities with more than 100,000 inhabitants across the world saw their populations fall during the 1990s. Future developments, however, are difficult to project, since urban populations are enmeshed in a multitude of regional, national, and global processes. Yet it is obvious that ongoing urban growth in the southern hemisphere will be increasingly paralleled by the process of urban shrinkage, especially in cities of the developed world. Without trying to make any predictions, I will sketch out some of the most relevant forces that will most likely have a more or less significant impact on future urban population developments.

Shrinking cities, 1950–2000. Shrinking Cities / Projektbüro Philipp Oswalt

Shrinking cities, 1950–2000. Shrinking Cities / Projektbüro Philipp Oswalt

Demographic change. The most predictable developments we can identify today are demographic in nature and can be projected with a high degree of accuracy on a national scale. In the 21st century, for the first time in history, entire countries will move from a centuries-old phase of population growth to a period of long-term population decline, including the Baltics, Bulgaria, the Czech Republic, Ukraine, and Hungary, as well as Belgium, Spain, and Italy. Urban population growth in the remaining European countries will over the longer term be minute. This demographic turning point will make shrinking cities an increasingly important phenomenon in the decades to come.

The Demographic Impact of Wealth. In many countries, a direct connection can be established between a decline in urban population and general economic prosperity. Because prosperity is a basis for some crucial demographic trends; it allows for mobility and suburbanization and it fosters low birth rates and the aging of populations. The number of shrinking cities has been correspondingly high in affluent countries. Until 1990, three-quarters of all shrinking cities worldwide were in countries categorized as developed countries. If this relationship between wealth and demographic development can be transferred, older industrial regions in developing countries such as India and China may experience similar processes of urban shrinkage in the future.

New Forces of Migration. Besides the overall demographic developments, which can be projected with considerable precision today, many other and sometimes unpredictable factors will have an effect on migration patterns and the demographic development of urban areas. These include rising sea levels, desertification, dwindling freshwater supplies, and the exhaustion of fossil fuels. The 20th century already gave us a foretaste of the destructive impact natural catastrophes may also have in the future. Not long since, scientists and NGOs began warning of a new wave of environmental refugees caused by environmental deterioration. Estimates range from 20 to 25 million today to 150 to 200 million in the future.

Conclusion

As I have tried to demonstrate, the industrial age was not only an age of continuous and exceptionless growth. In many ways, industrialization has also triggered processes of decline. At the same time, the industrial city with all its problems and challenges gave birth to modern urban planning as we know it today. And it gave birth to an anti-urban discourse which has inspired many architects and planners to experiment with ideas of decentralization and even with shrinkage. For a long time, shrinkage was not recognized as a problem, but rather as a concept against the failures of urban density and accelerated growth.

It was not until the end of the previous century and the beginning of the new millennium that planners – especially in England and then in Germany – recognized shrinkage as a challenge. In this context, urban planning found itself confronted with two paradigm shifts. Firstly, the primacy of urban growth, which has defined and legitimized urban planning for more than 100 years, has unexpectedly been complemented by an opposite trend ‒ urban shrinkage. But all of the means and methods in urban planning that had been developed and practiced in order to control urban growth proved to be insufficient. Secondly, while urban shrinkage was long perceived to be a favourable development in order to alleviate the plague of rapid urban growth, it was now perceived as a symptom of crises. In the context of an increasingly globalized economy, where direct competition among cities and regions came to the fore, shrinkage is no longer seen as an advantageous condition.

Moreover, besides their lack of experience, architects and urban planners were usually confronted with urban shrinkage at a time when the process of decline had already reached an advanced stage: empty apartments, debilitated infrastructures, and public budgets pushed to the limit. Architects and urban planners found themselves in a situation where they could only react to the given circumstances rather than draw up plans for future developments.