- INTRODUCTION

- LECTURES

- A_Mart Kalm / Modernism In Estonia: From Industrialist’s Villa To Kolkhoz Centre

- B_David Crowley / The Fate of the Last Generation of Ultra-Modernist Buildings in Eastern Europe Under Communist Rule

- C_ Claes Caldenby / Urban Modernity. Nordic-Baltic Experiences

- D_Marija Drėmaitė And Vaidas Petrulis / Modernism In Soviet Lithuania: The Rise And Fall Of Utopia

- E_Anna Bronovitskaya / Glimpses Of Today In Visions Of Russian Avant-Garde Architects

- ESSAYS

- Ernestas Parulskis / Commemorative Plaques In Lazdynai

- Indrė Ruseckaitė and Lada Markejevaitė / Elena Nijolė Bučiūtė’s Personal Modernism

- Maija Rudovska / In The Shadows Of Nostalgia. Marta Staņa’s Legacy In Latvia

- Liina Jänes / Position Of The “Other”: The Architecture Of Valve Pormeister

- Julija Reklaitė / Amber Inclusions. What Modernist Memorabilia Can Tell Us

- INTERVIEWS

- Talking About the Richer Picture. An Interview with David Crowley by Aistė Galaunytė

- An Active Archive For A Public Discussion. An Interview with Hartmut Frank by Eglė Juocevičiūtė

- Cheating The Space Or Cheating The Time. An Interview with Frédéric Chaubin by Eglė Juocevičiūtė

- More Freedom, More Privacy. An Interview with Anna Bronovitskaya by Eglė Juocevičiūtė

- Sinchronicity of Ideas. An Interview with Andres Kurg by Eglė Juocevičiūtė

- Recycling Socialism. An Interview with Aet Ader by Viktorija Šiaulytė

- ABOUT

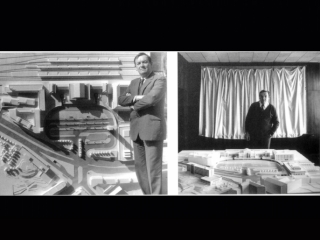

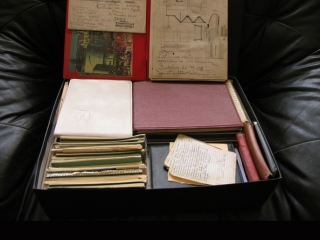

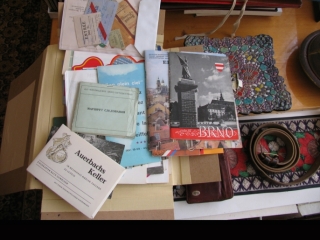

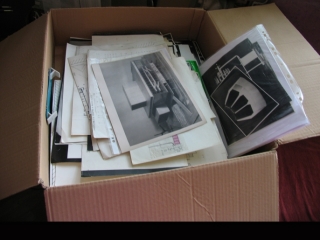

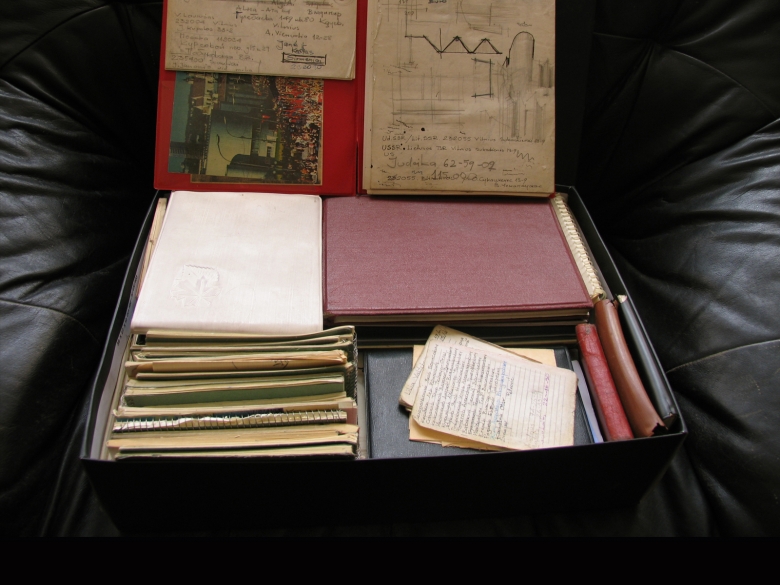

Domestic archive of architect V. E. Čekanauskas. Photo from project "Galimas modernizmas" ("Possible modernism")

According to Svetlana Boym, by the mid 19th century nostalgia had become institutionalized in the form of national and regional museums and memorials1. This is how the past became heritage. As soon as the publication of albums and poems started in the middle of the 19th century, the strange charm of memento mori was perceived by the collecting of various artefacts. Eventually such peculiar souveniring became an interactive, playful and dynamic way of communication providing a certain scenography to social life. In other words, details taken out of their context aroused the imagination of Europeans and served as illustrations to unwritten narrations about their owners.

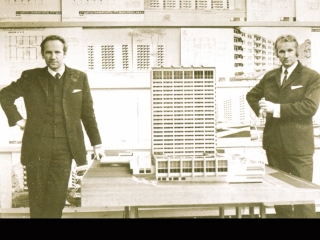

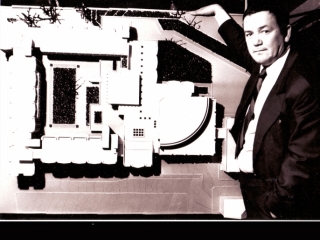

But nostalgia doesn’t always talk about the past, sometimes it is also related to the future. As an old Russian proverb goes, the future is more reliable than the past, because it is the only truly invariable dimension, at least for the present moment. But is it really so? Does the future pictured (back in the Soviet times) by Lithuanian masters of architecture coincide with the nostalgic past and the distorted reality of the time? What can the generation of outstanding Lithuanian architects-modernists, who worked under the hard and complicated postwar conditions, tell us about the past and future that was projected back then? What kinds of souvenirs have been collected by the brightest and probably the best self-realized architects and what can they really tell us? How is the Soviet reality reflected in the personal archives of Vytautas Edmundas Čekanauskas, Vytautas Brėdikis, Algimantas and Vytautas Nasvytis, Nijolė Elena Bučiūtė, Algimantas Mačiulis and Justinas Šeibokas?

The subjects of this essay are the scrappy fragments of design projects and life, the piles of paper and other substances that have been without any reasonable cause preserved in personal archives. They can tell us about the creative zenith, the youthful prospects and the ambitions of Lithuanian modernist architects. As a rule, when collected without any particular system, personal archives are chaotic, random and intuitive. The bare facts of their presence/absence and bunching/juxtaposition can tell many stories about the architects’ personalities and creative work, and also about the real and assumed reality and their discrepancies – about the work ‘for a brighter future’, realizing at the same time the pointlessness of the situation, about the architects-gods playing with the system and architects-human beings trying to survive in the system. Such personal archives can definitely show us much more than museum catalogues which are tended to mathematical systematization or curated exhibitions in which it is impossible to cover every detail. Such fragments of official and personal history are like a message in a bottle, which although being short and patchy may be very eloquent depending on who is going to read it and under what circumstances2. According to one of the five paradoxes by Rem Koolhaas3 any preservation and keeping tries to balance between memory and nostalgia. Therefore, while searching these personal archives and forming new collections based on such archives, it has been interesting to find how much they can tell us of the embellished, romanticized and thus paradoxical past, and how much just revive certain memories. How beneficial can this act of searching personal archives be as a method of collecting and interpreting information? And how can the value of items and our understanding of them be changed by collecting, keeping and reselecting such items?

Collecting is a systemic and purposeful gathering of items that are no longer used according to their initial purpose, but have certain scientific, historical and artistic value. Thus, collecting is also an expression of power. Every collection is made with the aim to admire, possess, remember (forget) and adore. Therefore, the practices of collecting or searching, reselecting and reviewing collections may be used to recognize power, restore the erased memories or simply as a research method.

The archive of Jacques Derrida, who introduced the concept of ‘archive fever’4, is important as a dual dimension of content and location because these are the two levels according to which it is possible to distinguish and track who is in charge of the information. In this concept the relationship between ‘private and public’, ‘sacred and profane’ are significant as well. Derrida also explores the issues of memory and archive together with memory and collection. According to him, an archivist has the power to unify, identify and classify items. Thus, there is no such political power which could not control archives if not the memory itself. Finally, an archive is related to a certain order or logic – linear (structured, democratic) or prescriptive (hierarchic). Protecting against forgetting in part erases the memory, because it can emphasize the details in an incoherent way and create new relations which deny the former ones. In this context, a newly created collection out of personal archive is interesting as a certain contextualization. This is an attempt to group the findings and under the changed circumstances regroup the logical thematic sequences. Thus, a new narration is developed by creating new paradigms of details and omitting certain facts. This is an infinite, never-ending process allowing for a different look at architecture – not as a result determined by the ideology of the time or just a cluster of forms and functions, but rather as a complex, overlapping, ideologized and very pragmatic self-recreating mechanism. Such an outlook cannot bring about any conclusions and the personal relationships with the creators destroy many critical prejudices and the same items can tell different stories.

The time patina covers not only the newspaper pages of the Soviet period glamorized by political slogans, but also adds more and more personal stories to the narrations of buildings, sometimes embellishing them, and sometimes some details are just forgotten as they proved to be insignificant, or – to be more exact – they are no longer significant. When you stop ignoring such an embellished layer of time and personal subjectivity, and when you let a narrator take such a position or such a role, which could carry him (or her) back to the nostalgic times, history becomes even more interesting. Subjectivity is turned into a double focus, when you allow it to flourish and all narratives interrelate. The issue of collection as a regenerating process and continuity then becomes relevant. By gathering and arranging such personal and subjective collections, you can also feel what such a collection has to say about its author and a particular period of time.

The archives of the architect Čekanauskas have been kept and arranged in a special way resembling that of a chronicle by his widow Teresė. The architect’s spirit is there in his works, photographs, tickets and piles of other dear knick-knacks, out of which she builds the pantheon of the great architect. In a lively conversation, Algimantas and Vytautas Nasvytis confess “we are not the collector-type guys”5. They are not attached to the past, and do not keep any things, they didn’t even like taking photographs of their trips because “when you fix the world through the camera lens, you fail to notice the most important details”. This does not come as a surprise because the entire generation of master architects are excellent draughtsmen. While talking, the brothers interrupt and start addressing each other. When you live and work as a duo sometimes you may forget some details expecting that your twin brother will remember them. Even the fame becomes double, and the responsibility is divided into two. Others call them just the ‘brothers’. This phenomenon of twins is very meaningful. When their colleague, the chronicler Algimantas Mačiulis collected material and prepared a book on them, he consolidated not a single myth nurtured by the brother-architects6.

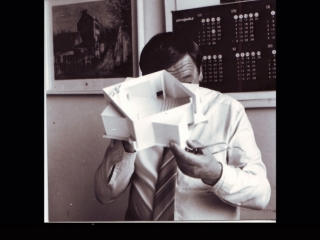

The archives of Algimantas himself are kept with precision, so that you can track the notes, diaries, restore images, accurate dates, names and surnames – it is a real treasury of information, where narrations keep overgrowing with concentric halos of facts and details. Whereas the similar archives of Vytautas Brėdikis are much more mystifying. This bohemian, free and philosophical in nature personality lets himself play with variations, interpretations and numbers, skilfully interweaving mythical and poetic details into his narration tissue. Justinas Šeibokas is just the opposite, he does not like mythology. He is rational, cool-headed, and does not try to conceal even the remotest inconvenient truth from anybody – whether that is others or himself. Looking to the world with a sharp and critical look, he crosses out the entire and diligently created myth of the gods of architecture with just one phrase: "signature style? Just take a look, such great architects but just a few realizations…”7 His archives are scattered – alongside the photographs picturing pranks of youth and unexpectedly to himself, preserved design models with long ago forgotten notes on the other side, everyday details – children, personal things and fragments of life – interweave. This comes as if proof that architecture to Justinas has always been nearby, his job is understood as a mission, a calling, like a second home or even more important than home.

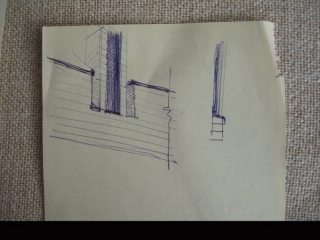

The case of Nijolė Elena Bučiūtė is similar. A very rational, constructive, exceptionally strong woman is revealed when on one side of a page she has made sketches of architectural details and structures, and on the other – a drawing of a dress or sweater for her boys. The ability to match architecture, life, bohemian and romantic plans and the challenges faced by this woman because of the time has remained a secret to me even after going through her very peculiar collections.

In the collections kept by Algimantas Mačiulis you can find many slides, lectures written in precise calligraphic handwriting. Special attention in his family archive is given to his travels and pieces of art – this reveals his quite bohemian nature and hospitality. Impressions brought from foreign trips were not only a source of inspiration to young specialists that essentially transformed their attitudes towards scale, form, and the materials used, but also a peculiar sign of honour. First of all, foreign trips were not available to everybody, for Expo’67 in Montreal, for example, only Algimantas Mačiulis was delegated from Lithuania. Secondly, they had an unwritten obligation that after coming back they would give their colleagues their impressions accompanied with photographs. Such type of public lectures were attended and valued, and the audience was interested in everything: what, how and out of what things were made, what products were available in stores – just a few lucky ones were able to see actual foreign architecture, not just from the pages of magazines.

The archive of Vytautas Edmundas Čekanauskas may be divided into two parts which complement each other. One of them is representative of the life, trips, souvenirs and sources of inspiration of the architect – pieces of art and folk art hang on the walls of his former work room. In his notes, the architect mentions that a natural and national context had always been important to him, Vilnius Old Town with its red gothic never stopped making impression on him. Whereas, the other part reminds one of a personal museum, which has been carefully looked after by his wife, as if in anticipation of the greatness of her husband as an architect. The archives of all the buildings designed by Čekanauskas marked with respective dates and illustrated with photographic materials on all stages, sketches, models, details, extracts from the press and sources of inspiration, together with foreign architectural magazines can be found here. You can see the original architect’s shots for the magazines of the time and the final published results. In this sense, Elena Nijolė Bučiūtė’s archive is absolutely different. She was interested in construction. While browsing the piles of her sketches, her portrait as a scientist is revealed. It is obvious that she sought for a rational background in making every important solution. The collection of her sketches does not resemble any archive – a precise filing system was not typical of her. It resembles more a testimony of her thought development, rather than an ambition to collect an archive for the future. Only full collections of foreign architectural magazines, difficult to obtain back in her time and obviously thumbed through very often, are carefully sorted, although the architect was not able to read in some of the languages, she was obviously very attentive to details and pictures. Whereas Vytautas Brėdikis has clearly kept a collection of his sketches, which can tell us more about him, his practice as a teacher, his search for certain rules in composition and the right colours, and less of the stories of the buildings. His trips also disclose more through their atmospheres – sketches drawn on maps, booklets and souvenirs, but never photo albums. While going though his design drawings you can also find quite curious things: a fisherman’s chair, a mousetrap and similar inventions erasing the boundary between architecture and life and revealing not only the author’s creativity, but also an ability to do something with the situation. Justinas Šeibokas thinks in volume blocks. Details and their variations seem unimportant to him. In the preserved binders you can find lots of photographs of sketches of the Lithuanian Cooperative Union’s building models, as the design project was submitted for the council’s approval 18 times. Now the architect is proud to remember what confusion his candidacy caused, as it was suggested for an award for his design of the Ministry of Communications building, because he had no commendations, only reprimands. In his collection the architect reveals himself as a creator without any taboos, compromises or restrictions, perceiving himself as a modernist in all senses.

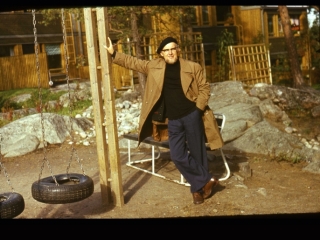

The act of collecting encompasses searching, finding, obtaining, arranging, filing, showing, keeping and looking after. Each of these actions gradually questions the issues of nostalgia and criticism. The question of power and value is reconsidered at each stage. In being collected, objects are taken out of their natural context. This means that their properties and interrelations are essentially changed. By the act of collecting, objects are transferred to some other, special, environment in which they serve a different purpose than their initial goal, and where they are treated, understood and recognized differently. In fact, this makes collecting the issue of value. And what about family archives? What can personal and non-institutionalized archives tell us about power, value and relations? On the one hand, they are closed, private and inaccessible, while on the other, the mere fact of them being collected is quite expressive forcing us to reconsider personal collections as public or at least potentially public – having the purpose of publicity and speaking about an architect’s public life. Personal collections tell us the stories beyond buildings and help to purify and check the creative intentions. Could it be true that even before planning the Lazdynai district, Vytautas Edmundas Čekanauskas anticipated his upcoming recognition and the first Lenin prize? Kept nearby the typewritten pages of the pompous Lazdynai speech, romantic photos of the architect going for a walk in the natural suburban environs at sunset betray this. Made by a professional photographer they capture the importance of the moment, the power of the architect’s mind and even the entire system – soon in these deserted meadows a pride inducing residential district will be erected.

According to John Carman8, creating a symbolic value to an object is not the sacralization of it, but rather an expression of the system in which it is (or was) present. Very meaningful in this sense is the context of making and remaking personal collections, and its transformation under the change of system. According to Thompson’s ‘rubbish theory’9, all objects may be divided into three categories: transient, the value of which is diminishing with time; durable, the value of which with time is growing; and rubbish, which have no value at all. In a sense rubbish is especially interesting as it is invisible/undesirable and can potentially regenerate their value by becoming something else. It turns out that architects’ personal archives may be essentially attributed to the latter category. In them the incongruity between real life and vision, intention and realization, value and cognizance can be clearly seen. In the official sense, when any official collecting institution and evaluation discourse exist (Lithuania has no architectural museum), an architect’s personal collection is rubbish. But when they are collected at home, re-sorted and recreated, their value changes with time potentially (and paradoxically) becoming more and more public and thus increasing the gap between planning ahead for the future and a contemporary retrospective look.

Some archives can inspire, while others reveal still unknown creativity layers – an abundance of variants of each object and detail, versions different to those which we are used to seeing, entire photo albums prepared for the Moscow’s certifications with precisely selected photos of sketches and realizations, collections of press clippings on the long-term realizations, as well as foreign magazines in any possible language as sources of inspiration. The ability to turn a narration one’s own way is often camouflaged by an unwillingness to speak or using prepared in advance phrases. After all in modernism everything must be clear without words. As the architects now affirm, they did not need to write themselves, information on architecture was popular and hungrily absorbed. Texts were needed in Moscow, when trying to prove why a building had to be this way and not the other, usually with the favourable rhetoric of a communist future or the fast and economical construction process that was being used. The often expressed sober and quite ironical outlook on reality betrays this to be the system of gratifying rhetoric. Gallows humour maybe, but when attempting to make details look similar and graceful like in Finland, the results were obtained quite differently because aluminium was a strategic material. The light and elegant tomorrow of a communist human being was required to make things as if out of nothing – naïve and youthful enthusiasm and prefabricated details – and the unexpected effect was achieved by replacing stairs with windowsills, and windowsills with stairs… But the unexpected was sought for. The unexpected even more for architects themselves rather than the system. Every architect wanted to be the first to implement a detail or a solution because it was a trademark of good architecture and success.

In Soviet times, the search for the original was gradually replaced by the search for novelty. To make anything for the first time meant competing with the system and time. Ideas and inspirations were borrowed from both the East and the West (sometimes in the form of directly copied details), because any information from beyond the border was deemed surreal. More important was under what conditions and when it was made. Even now architects are especially good at remembering dates and details, still able to recall which object, concept or sketch was the first. In such, to some extent weird, way an architect’s ability to manipulate and persuade was understood as proof of his creativity. Somebody, who had succeeded in concealing brass roofing by covering it in an alloy suggested by a chemist from Neringa, found out how to make round illumination lamps look like foreign ones with the use of the cases of Saturnas vacuum cleaners… It seemed like something had been created out of nothing. Are these just the coincidences that are often mentioned in conversations? “Lucky coincidences,” – the Nasvytis brothers agree also understanding at the same time that their generation have faced extraordinary possibilities to plan and design exclusive buildings: opera and drama theatres, government and parliament palaces, museums, and ministries10. They also allow me to come to reason that such coincidences are quite regular; but they don’t happen to everyone and not all the time.

Inadequacies between the state of wellbeing and reality are disclosed while looking at the gaps of personal attitudes and public opinion, especially snippets of trips – slides, souvenirs, press, notes and memories. The most precious moments of trips, small and cheap souvenirs and other pleasant knick-knacks are stuck like flies in amber inclusions brought back home a tiny part of Finland or America, although now they look ironically small. The huge gap between here and there is illustrated by the emotional and carefully written travel notebooks recording every detail: the number of buildings visited, number of hours the dinner lasted, the number of pools with saunas and the price of… soap. After coming back the nostalgia was even stronger. Like Vytautas Edmundas Čekanauskas wrote somewhere in the margins of his notes while taking a holiday on the Lithuanian seaside: “excellent, so much like Finnish weather…”11 Probably the most precious of all relicts, an Alvar Aalto autograph, about which all later generations of Lithuanian architects have heard, is kept in the very centre of V. E. Čekanauskas’ work room. In fact it is related to a story of great frustration, when visiting Aalto’s office, Čekanauskas failed to meet and communicate with his so admired architect, and only succeeded in getting from a trainee a sketch drawn by the master’s hand. Ironically, the sketch framed and exhibited in the centre of the room used to cause many discussions about which building it reminded of…

Such browsing in personal treasuries is a fairly venturesome, but also a very personal act. Collections arranged in this way are changing and endless, often reselected, able to tell different stories every time due to their changeable and sometimes unconscious character. According to Svetlana Boym, nostalgia is a sentiment for loss and shift, but also the romanticism of fantasy. The cinematographic image of nostalgia always has double focus – home and abroad, past and present, dreams and daily life. Modernist memorabilia just like amber inclusions is mysterious and fragmentary, and tells us the story of past times transferring us to the nostalgic past, or even – to be more precise – to the future of the past. Architects’ personal collections are sort of lost in time. But they are still to find their place. The number of such collections, just like their collectors and new stories told by them, may be infinite, due to the undeniable fact that personal memory is a variable dimension.

1 Boym S., The Future Of Nostalgia, Basic Books, 2001, p. 15.Boym S., The Future Of Nostalgia, Basic Books, 2001, p. 15.Boym S., The Future Of Nostalgia, Basic Books, 2001, p. 15.

2 The material from the project Possible Modernism curated by Audrius Novickas and Julija Reklaitė, 2011, is used in this essay.

3 Five subjects and five paradoxes suggested for the STRELKA school, Rem Koolhaas, http://betacity.wordpress.com/tag/rem-koolhaas/

4 Derrida J., Archive Fever, The University of Chicago Press, 1998.

5 From the conversation with A. and V. Nasvytis in the Neringa restaurant, Vilnius, 26 March 2011.

6 For example, usually this generation architects like presenting themselves as a very unanimous, solid and pure-modernist group or community of creators who followed a single canon, but when interviewing them you get the impression that these architects also cherished their personal signature-style and there was a certain competition inside the group for larger commissions and design realizations.

7 From the conversation with Justinas Šeibokas at his home, 6 May 2011.

8 Carman J., Promotion to Heritage: How Museum Objects Are Made, p.74, // encouraging collections mobility ‒ a way forward for museums in Europe.

9 Thompson M., Rubbish Theory: The Creation and Destruction of Value, Oxford University Press, USA, 1979.

10 Drėmaitė M., Modernizmas galimas. Audriaus Novicko paroda „Galimas modernizmas“ Šiuolaikiniame meno centre (recenzija), in: Kultūros barai, Nr. 5, 20Drėmaitė M., review of the A. Novickas exhibition "Possibe modernism", in: Kultūros barai, Nr. 5, 2012, p. 50-52

11 From the findings of V. E. Čekanauskas’ memorabilia in his home, Vilnius, 15 June 2011.

Straipsnis PDF formatu:

http://leidiniu.archfondas.lt/sites/default/files/117-128_essay_julija%20reklaite.pdf