- INTRODUCTION

- LECTURES

- Jüri Soolep / Education In, Of and Off Architecture

- Kazys Varnelis / New Paradigms in the University: Research at the Netlab and Studio-X

- David Garcia / What Exists is a Small Part of What is Possible

- Albena Yaneva / Mapping Controversies in Architecture: A New Epistemology of Practice

- Dr. Nimish Biloria / Info-Matter

- INTERVIEWS

- ESSAYS

- ABOUT

Aistė Ambrazevičiūtė,

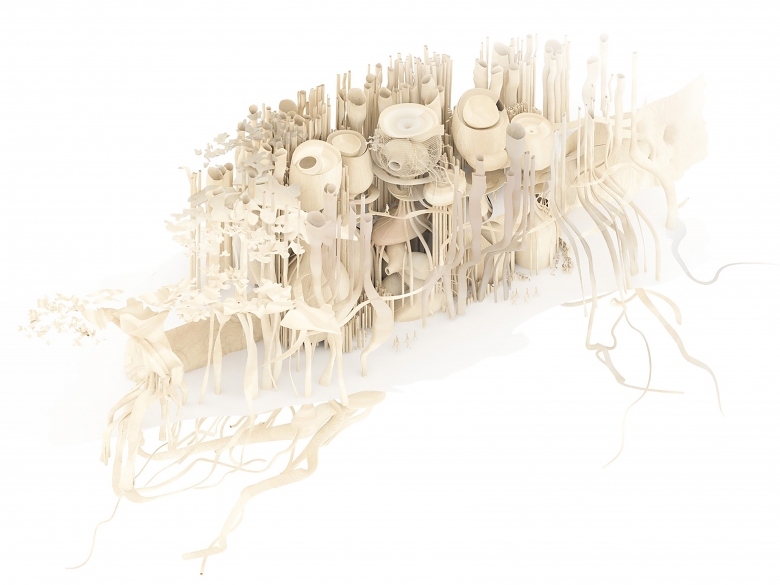

Imaginary Folklore - Recreating the Landscape, Fine Arts Academy Vienna, tutors: Kathrin Aste, Michael Hansmeyer, Wolfgang Tschapeller, 2016.

„The project’s design is based on the complex wood anatomy and material investigation, combining various scales and parts of wood, which enabled to discover new unseen forms out of wood. The aim of the project - to rediscover wooden architecture and its design parameters.“

I am interested in architectural research, creative experiments, pursuit for ideas and consistent project development. In the studies of architecture, as well as its practice, these are the fundamental parts at the core of any good project. Schools of architecture enjoy an exceptional opportunity to engage intellectual thinking, gather together experts in different fields and explore relevant problems, extensively and elaborately go deep into the essence of issues, offer innovative ways for their solution. Critical thinking and spatial analysis not only provide for a solid background for a good study project, but also encourage the community of architects and other professionals to focus on the existing and newly evolving problems, their causes and outcome, as well as potential ways of solution.

Why more research and explorations in architectural studies should be encouraged? First of all, I think, a research in architecture helps to tackle two fundamental questions: (i) scanning architectural space and identifying the emerging problems, still invisible in architectural practice (it contributes to figuring out the potential challenges and threats in the long-term perspective, forming sustainable and coherent principles for the planned modelling of architecture development) and (ii) search for new research methods by experimentation, new architectural principles, innovative technologies and finding ways of their application in architecture practice.

I present this text as a dialogue with different experts in architecture – teachers, school leaders, who share their insights about research and pursuit for ideas in their architectural and educational practices. At the Royal Danish Academy of Fine Arts, Schools of Architecture, Design and Conservation, the Strelka Institute for Media, Architecture and Design in Moscow, and FUTURE+ Aformal Academy of Urbanism, Landscape and Public Art in Shenzhen, China, the interdisciplinary approach, innovations, research and experimentation are inseparable parts of education, in order to educate specialists capable of solving problems or exploring contexts of work and research fields, which today still do not exist, capable of looking for solutions for the most urgent challenges of the day. Therefore, in the text, the representatives of these three educational institutions share their opinions, insights and thoughts on research in educational process.

One of my interlocutors Jason Hilgefort (urbanist, head of the FUTURE+ Aformal Academy for Urbanism, Landscape and Public Art in Shenzhen) notices that correctly formulated question or emphasized key problem often may be even more important than methodical, consecutively performed project and are of more value not only to a student, but also the audience at large. The FUTURE+ Academy under his guidance does not follow the established canons, but rather attempts to foster future leaders by expanding the field of architectural thinking without restricting themselves by the existing specific design and research methodologies.

When asked about creativity in studies, Jason Hilgefort answers: “In many ways what we focus on is creating leaders. We do not believe ‘we know how to do it’ attitude. We encourage our students to try new ways, make mistakes and then we all discuss it together. And this is another key aspect, they are encouraged to debate with each other and the professionals. We think it is good to play and laugh, and experiment. School is a place to try new things, but not a place to be taught a particular methodology.

For us, the studies of spatial practice (architecture, urbanism, landscape, etc.) is not so much focused on only space designing or aesthetics. We try to encourage our students to be more aware of the forces that impact on how spaces are made – political, demographic, economical and other processes. We try to fight the cult of visual material (drawings) that, in our mind, has come to dominate too much and dictate to the spatial practices and sciences. With the use of sections, plans and renders only a very narrow point of view is set. But there are many more manners of expression to explore and create architecture, urbanism or landscaping.

To begin with, we do not teach our students ‘a way’. We certainly encourage them to engage in questioning in a number of ways depending on their skills (for example, with the use of films, interviews or statistical analysis). We also encourage them to test the ways, which they and often we are not used to. We strongly push them to both think analytically and abstractly creative at the same time. For the sake of something new, still undiscovered… We also encourage the sharing within a group. The process is not ‘yours’ and ‘mine’. We are exploring and collaborating to learn, but never competing for better grades. We see it facilitating them to find their own creative path, their own methods, rather than dictating a dogma.

For us, it is important to see all the systems and processes that often architects just take for granted. To understand the process first. Who is doing the commissioning? Where is the money for the project coming from? What is the goal of the developer with this project? How does energy get to the site? Where does the water come from and go? How will management of the site work after it is built? What other forces, influences can we use to impact, affect the project? What else could or should be there? If not now – even in a few years? The notion that we strive to have is putting a priority on, but not hierarchy. Thus, this way of learning goes in all directions.

Architecture, urbanism, landscaping, etc. – all these spatial practices cover many aspects. Some students want to detail windows, but many don’t. Some are interested in dealing with political motivations behind commissions in their future careers, some are less so. We attempt to keep the program broad, with “deep valleys”, so that each student could find his/ her own activity map, just in opposite to the broadly used standardized typologies of graduates.”

Whereas Kuba Snopek (urbanist and researcher, tutor at the Strelka Institute of Media, Architecture and Design in Moscow) emphasizes the importance of correctly formulated task for the study work aimed at the grounded result:

“I believe in the importance of two components that architecture students don’t give that much attention to: the brief and research. First of all, the brief must be formulated correctly, approved by and fully clear to all groups of the common process. Secondly, in the research, the essence often is to understand properly the function of the building, or how it should perform. I always try to get to the core of it – what is a theatre? What is a dwelling? What does it mean to read a book or to pray? For me, a research definitely does not start with the site, but with the core function the building is about to perform.

The process of research (that actually leads to establishing the core idea of the building) is always very similar by its structure, but differs in thousands of details in every given case. It consists of the following parts: (a) data collection and a quick research of all related fields; (b) recognition of patterns in the collected data; (c) naming the patterns; (d) “ideation” – application process of the recognised patterns in a specific case.

The essence is simple: answering one underlying question – ‘WHY?’ In every project done at Strelka and by myself, at every single stage of it, the development motives must be clearly set. To put it simple, every time you draw a line, you should understand WHY you are drawing it. Architecture always needs to have a strong rationale.”

Arne Cermak Nielsen (Danish architect, partner at BCVA and teacher at Copenhagen Royal Academy of Fine Arts, School of Architecture) adds that it is also important to find a potential of a place, its added value, which is sought after by himself in his practice and his students’ works. He says:

“Study programmes, I believe, should always have some kind of social starting point, be socially responsible. Any current issue, crisis or urgent need can be addressed through the prism of architecture or urban planning. While designing in a specific territory, the livability of the environment could be increased, for example, by creating a public space or unique building offering something in return to the space it occupies. By identifying such livability aspects, projects of the students may gain greater value. Many global, national and local issues can be addressed fully or partly by the means of architecture and urban planning. I therefor recommend the students to follow the news, debate and statistics in order to locate the scope of their projects.

Often it is hard to persuade private clients to seek for social responsibility on broader scale, so it's essential to tell them what their benefits are. Some cities in Denmark, however, are able to formulate their consecutive urban architecture policies and action plans, which we can use as guidelines together with the clients. It certainly helps the dialogue with the authorities if the client and adviser understands these soft values as well - and not just the legal restrictions of density, program and building heights.

Similar approach is also declared by Slavis Lew Poczebutas (partner of MEKADO architectural studio, Berlin, former project director at OMA, guest teacher at different universities), has been a guest professor at VGTU over the last years, working with local students in the format of short and intensive design and implementation workshops. When he started to teach at the architecture faculty, the format of workshops as means of experimenting intensively and freely on certain topics had not been established yet, but explored and tested successfully since.

He is encouraging the faculty to continue to open up the dialogue and format of teaching to explore and debate on pressing challenges of our contemporary and increasingly complex life which evolves and changes around us. Architecture schools need new methods of architectural and urban thinking and organization to develop solutions for a progressive urban future. The architectural education has to encourage students to be curious, asking questions, be critical and to develop their own passion and creativity for topics on and beyond architecture that today have an increasing influence on the urban world and its inhabitants and users.

So, the experts from different places of the world I have talked to say different things about creativity, they apply different methods and develop different projects, but they have unanimously stated the importance of research and experiment in the process of finding any given project’s essence, nature and problems. In addition to this, all my interlocutors have emphasized the need for intensive work not only among students, but also teachers, which is actually happening in their alma maters – each lecture requires intensive preparation work, work during it and a lot of discussion and/or reflection after it. Teachers compete thus attempting to maintain high quality of studies in different groups or departments.

To solve the issues (or rather challenges) that recently appear in Lithuania requiring complex and uneasy solutions, just the good practice examples from abroad are no longer enough, they require innovative and unique ways of solution, as well as complex, strategic and creative exploration path. For meeting such challenges, cities also need entire teams of experts, including not only urban planners, architects, constructors, but also politicians, designers and even urban activists.

Today, an architect, urban planner or landscape designer has to be capable of not only solving the emerging urban problems on the professional level, but also finding, identifying them. Teaching how to find out, understand and evaluate complex problems and challenges, discuss and hear other opinions, find common vectors for activities has to be the prerogative of schools of architecture. The schools mentioned in the text still learn themselves how to discover, understand and perceive, and they help different organizations and institutions in doing this. By gathering experience through study researches, the STRELKA Institute works in collaboration with different institutions in organizing competitions and other urban processes important for the city of Moscow. Teachers and students of the FUTURE+ Academy give lectures and creative workshops to pre-schoolers, elderly people and local communities. The distinctive feature of work of Copenhagen Royal Academy is presentation of its students’ graduation works to experts of different areas, town residents and even tourists at large exposition spaces.

Without any doubt, the primary mission of any university is training a good professional in a certain area, but a university has also to be the place, where important issues can and, I believe, should be analysed, causes and ways of solution of different processes looked for, strategies developed for possible city scenarios, discussions among experts held and society at large enlightened. The schools of architecture discussed in this article are good examples of how architectural education trespasses the boundaries of just teaching technical subjects. All the interlocutors have emphasized the importance of fostering a self-confident personality able to think, gather and analyse critically the information, create innovations and trespass the boundaries of sticking to standardized and established methods in preparation of any project – of a house, city, street, park or even a computer software.

Ignas Uogintas is an architect and partner of DO ARCHITECTS office since 2015. With the DO ARCHITECTS team, he works on such projects as the territory development of Svencelė, Ogmios Miestas in Vilnius, Misionierių Namai, the apartment block quarter in Vilnius. Before joining the DO ARCHITECTS team, Ignas worked with different architecture offices in Lithuania, Spain, Poland, Netherlands and Denmark gaining different professional experience.

Ignas Uogintas graduated from Copenhagen Royal Academy of Fine Arts, School of Architecture, studied at the Academy of Architecture in Amsterdam and Vilnius Gediminas Technical University, the Faculty of Architecture. In his graduation work for the Master degree, Ignas analysed the history, problems and development possibilities of Pašilaičiai residential district in Vilnius, from small interventions to the entire regeneration of the district. Ignas Uogintas’ graduation paper for the Bachelor degree has won an award of the best study project in Lithuania.

The major part of his projects, researches and studies has been related to analysis of architectural and urban structures in cities and their development in problematic territories focusing on broader spatial, sociocultural, economic and other contexts.