- INTRODUCTION

- LECTURES

- A_Mart Kalm / Modernism In Estonia: From Industrialist’s Villa To Kolkhoz Centre

- B_David Crowley / The Fate of the Last Generation of Ultra-Modernist Buildings in Eastern Europe Under Communist Rule

- C_ Claes Caldenby / Urban Modernity. Nordic-Baltic Experiences

- D_Marija Drėmaitė And Vaidas Petrulis / Modernism In Soviet Lithuania: The Rise And Fall Of Utopia

- E_Anna Bronovitskaya / Glimpses Of Today In Visions Of Russian Avant-Garde Architects

- ESSAYS

- Ernestas Parulskis / Commemorative Plaques In Lazdynai

- Indrė Ruseckaitė and Lada Markejevaitė / Elena Nijolė Bučiūtė’s Personal Modernism

- Maija Rudovska / In The Shadows Of Nostalgia. Marta Staņa’s Legacy In Latvia

- Liina Jänes / Position Of The “Other”: The Architecture Of Valve Pormeister

- Julija Reklaitė / Amber Inclusions. What Modernist Memorabilia Can Tell Us

- INTERVIEWS

- Talking About the Richer Picture. An Interview with David Crowley by Aistė Galaunytė

- An Active Archive For A Public Discussion. An Interview with Hartmut Frank by Eglė Juocevičiūtė

- Cheating The Space Or Cheating The Time. An Interview with Frédéric Chaubin by Eglė Juocevičiūtė

- More Freedom, More Privacy. An Interview with Anna Bronovitskaya by Eglė Juocevičiūtė

- Sinchronicity of Ideas. An Interview with Andres Kurg by Eglė Juocevičiūtė

- Recycling Socialism. An Interview with Aet Ader by Viktorija Šiaulytė

- ABOUT

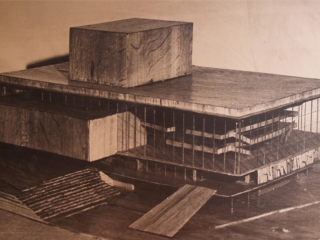

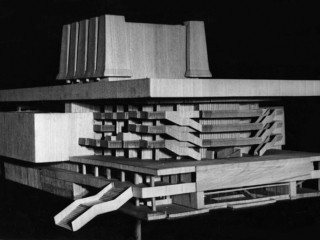

Elena Nijolė Bučiūtė next to the model of the Opera and Ballet Theatre (1960). From family archive

Some of the post-war architects’ generation who would form the foundation of the Lithuanian architecture were born in 1930,1 the year when the 500th anniversary of Vytautas the Great’s death was somewhat enthusiastically commemorated all over Lithuania. The government of the time promised to provide free university education to any child born in this year. Knowing she would have a choice in her studies, Elena Nijolė Bučiūtė (1930-2010) dreamt of becoming a geographer. Following the year 1945, however, after Lithuania had been annexed to the USSR and the geographical boundaries of such possible journeys and explorations had narrowed, she was forced to re-evaluate her dreams. Elena Nijolė graduated from the Faculty of Architecture, the Institute of Arts of the Lithuanian Soviet Socialist Republic (the present Vilnius Academy of Arts), and, without looking back at the past and regretting the unfulfilled geographer’s career, she became engaged in designing exceptional buildings and became one of the brightest Knights of Architecture of her generation. It is interesting that in one of her most outstanding works – Vilnius Opera and Ballet Theatre (1974) – she managed to expand the geographic boundaries of inspirations and modernist rationality of the Lithuanian school of architecture. In terms of the means of expression she used in the design of this theatre, in association with the influence of Scandinavian architecture and the search for a national identity, two other elements were present. The first was the richness of architectural and design details designed by the architect’s life partner, the artist Jurijus Markejevas, who had a Russian background. Such elaboration of details was very uncommon for Lithuanian modernist architecture, which mostly relied on the Scandinavian tradition. The second was the intertwining of the architects and the artist’s personal nostalgias in these details, which introduced certain shades of subjectivity alongside the popular at the time trend of the search for national identity. Such innovation to the Lithuanian school of architecture had previously been severely criticized by colleagues.

The narrative on the Opera and Ballet Theatre, as on any other modernist building or even the entire style of modernism, can be constructed in two ways. On the one hand, modernism is often treated as some abstract/anonymous phenomenon, and on the other, it may also be personalized. In the first case, modernism is explained as if standing next to some model of a building or observing it from a bird’s eye view – this was the way in which urban and architectural “prides” were introduced during the Soviet times. In this case the charge of the universal modernist message declared by a building, its volumetric-spatial and structural solutions and innovations are marked. An architect is understood as a ‘hero-creator’ constructing the space, form and even lives of others, embodying the ideas of the time in huge models in a scale of 1:1. An absolutely different face of modernism is revealed when looking at it ‘from the inside’. If one asks architects to make ‘archaeological excavations’ into their personal archives and listens to the memories of their family members, some other profiles of an architects’ work start coming to the surface. Subsequently, a modernist hero-architect becomes more human and starts talking in subjective terms, explaining his/her personal inspirations and nostalgias that are encoded in the architectural details, and such private aspects do not necessarily echo either the spirit of the time or the national identity. Thus exactly the same two narrations can be developed while speaking about the National Opera and Ballet Theatre. A lot has been spoken and written on the architecture and creative context of this object ‘from a bird’s eye view’. Our aim is to present this object ‘from the inside’ with the help of the story told by Lada Markejevaitė, the daughter of the architect and the artist. It reveals the emotional link of the two creators to the building and its very personalized details.

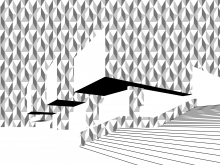

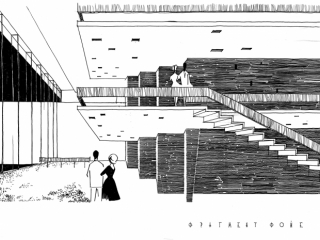

“It was so unlikely – she was never a communist and besides she was a woman of such a young age,”2 but nevertheless in 1960 Elena Nijolė Bučiūtė won an architectural competition to design the Opera and Ballet Theatre (OBT) with the Institute of Urban Construction and Planning of Vilnius City. Starting with the initial design stages of the theatre, the architect developed the one-piece high space of the main lobby surrounding the volume of the auditorium. This unusually open, vertically extended proportion of the space was a comparatively new solution in Lithuanian architecture and raised a lot of professional discussion. In reference to the design project, other architects expressed their doubts concerning, in their opinion, the too large and too tall lobby space, and expressed reservations as to its intimacy. One of the Bučiūtė’s arguments in defence and reasoning of such spatial character of the lobby was her childhood memories and impressions of sacred processions held in the yard of the red brick neo-gothic church in Rokiškis. According to the architect, she had never felt any discomfort while going around such huge brick walls. On the contrary, she could feel strong, solemn, being in extraordinary spirits: the powerful brickworks of the church (similar to the volume of the OBT auditorium), the surrounding open space of the churchyard (analogous to the panoramic view of the city opening through the glazed walls of the lobby) and the high sky (very much like the ceiling panel of the lobby practically vanishing in its twelve metre height) generated the convivial character of the space.

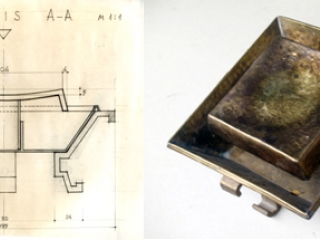

Starting with 1968, when the detailing stage of the design solutions was reached, the former laconic functional character of the Opera and Ballet Theatre started to change. Taking into consideration the many-sided and rich character of the opera genre, Elena Nijolė sought to emphasize it by the interior solutions. At this time, the architect’s second marriage partner Jurijus Markejevas joined the theatre design team. With his artistic origin, creative energy and respect for history and tradition he supported the architect’s creative quest and was a great help to her in designing the finish and architectural details. In the architectural solutions that had been made in 1962, one could see the accented red volume of the auditorium – the only coloured finish material used in the design. Back then, the character of the volume finished in red facing bricks was important. Later the architect did not happen to mention the closeness of red brickworks present in defensive structures of ancient Lithuania and church buildings to her architectural perception. This traditional material and its application in modern buildings seemed an especially organic solution to her. Nevertheless, this choice of hers had faced certain opposition from other architects, as red brick was considered too simple to be used in a public building of such significance; a much more acceptable finish material at the time was grey dolomite. Jurijus Markejevas, however, was very enthusiastic and supportive about Bučiūtė’s wish to use red brick for the finish of the theatre. Now we can only guess that such selection of clay and ceramics as a facing material by both creators was not accidental, but rather somehow encoded in their childhood memories. Both the architect’s native region Rokiškis and Markejevas’ grandparents’ land in the Vladimir region of Russia had special clayey soil and this determined the presence of traditional pottery craft in their childhood environment and even games of modelling from clay. Finally, Jurijus Markejevas designed the industrial samples of five different purpose-made bricks to be used for the cladding of the theatre walls. With the help of such decorative purpose-made bricks and their different lining Gothic brickworks of St. Anne’s Church in Vilnius, Perkūnas’ House in Kaunas and Zapyškis Church would be repeated. Production technology of such purpose-made bricks specifically for the theatre was developed in Jašiūnai Pottery Plant according to the production technology of ceramic drainage pipes applied in the plant. But this technology had failed to be further developed for the making of industrial samples of other items.

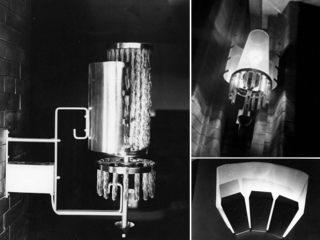

Another interesting element used in the interior of the Opera and Ballet Theatre was yellow glass. At the time, cut glass was the most popular material used in the production of chandeliers meant for important public-purpose buildings. Nevertheless, in order to increase the warm colouring of the interior, the designers commissioned yellow glass, which was used abundantly in developing different models of the chandeliers and glasses for drinks designed and tailor-made by Jurijus Markejevas especially for the Theatre buffet. Elena Nijolė often mentioned the inlays of coloured glass used in the glazing of manor buildings or even the verandas of ordinary peasants’ residential houses. Her own fascination with coloured glass reflected in the colourful glass decorations and compositions of simple glass bottles collected by the architect and kept in the daylight on her window sills. This simple playfulness of yellow glass – a cheap material – had outrivaled the ‘noble’ cut glass. In addition to this, brass, always referred to as a traditional Lithuanian material by the architect, also had a role to play in creating ‘the music’ of warm tones. Brass was not only used for the plinths, but also oddly occupied the space. Brass elements from suspended chandeliers on the level of the box office lobby, repousse purpose-made plates facing the columns and entrance doors, door handles, ashtrays and the decorative fireproof curtain – were all details that were the tailor-made solutions of Jurijus Markejevas for this design project. Technology reminiscent of that of a blacksmith’s reflected the artist’s nostalgia for the ancient craft: intricate bent ashtray profiles, door handle details, even the elements made of special light brass-imitating alloy reflect the author’s admiration of the blacksmith’s technique. The final shape of the decorative fireproof curtain resembles the ancient roofing and dome covering technology, where the elements overlap like the scales of a fish. Looking at the sketch proposals of the same curtain, one can see some other parallels – of an ancient warrior’s armour joined of separate rings.

Markejevas attempted to embody this nostalgic quest for the lost festival not only in applied materials, but also in modelling the rhythm of the visitors’ motion. He designed the main entrance outdoor staircase by matching it to the common ‘noble’ character of the theatre, as if attempting to negate the usually over-emphasized simplicity and mundane routine of the Soviet times and instead turning to the destroyed spirit of aristocratic celebration. According to the designer, the width of the staircase, its low, but quite deep steps and low handrails were introduced to reflect the nature of ‘royal’, solemn and slow walking. The stairs were designed to orientate the arriving visitors – Soviet people – towards the performance and the amazing festival. Here we should also mention the very specific trajectory of audience movement that has formed over the years. It is quite odd: during the intervals the crowd starts to walk in a circle around the lobby and everyone, including new-comers, joins the procession. By the middle of the interval one can observe from the balcony a massive promenade with its participants demonstrating their grand statures and occasional clothing.

Thus, such a view ‘from the inside’ based on stories by architects themselves allows the observing of the building from a different angle – a more personalized, multi-sided view, having in these small details a much more intense narration than one can expect while looking from the perspective of ‘the bird’s eye’. High-quality with the precise play of details, highlighting the rich, multilayer, luxurious and even prop-like character of the opera genre was the author’s conscious choice. This also triggered considerable criticism of the theatre by its contemporaries: “too many expensive materials used, a multiplicity and overload of architectural forms and details, as well as a shortage of stylistic unity and modesty in the building”.3 In the 1970s, “the unity of function and artistic form, along with the frugality adopted from the folk architectural traditions, application of local materials, and ‘logical’ decoration without any excessive splendour”4 were considered the strongest and most positive features of the Lithuanian school of architecture. The new theatre was also expected to become the building of the time, reflecting the common achievements of Lithuanian architecture. The initial design stages of the National Opera and Ballet Theatre (1960 and 1962) had revealed the common creative quests of the Lithuanian architects of the beginning of the 1970s. The clearly functionalist character of the building later obtained some features of late modernism, such as more complicated volumetric forms and their different textures, segmentation of the stage (traditional modernist rectangular) into a smaller, multiple structure. The design solutions of 1968 reflected the trend of the late modernism “to make a more intense emotional connection between a building and its viewer by the new architectural means of expression”.5 Similar to personalized modernism, the subjectively chosen historical signs and traditions encoded in the details and the irrational decorativeness of the building may be ascribed even to qualities of post-modern architecture. Thus it could be stated that the third stage of the design (1968) failed to comply with the canon of the correct Lithuanian architecture and the prevalent trend of architectural pursuit of the time. Looking retrospectively, it is no wonder that the architects’ community had some difficulty in accepting the Opera and Ballet Theatre, which went beyond the boundaries of laconic architecture. Elena Nijolė Bučiūtė, however, “had never swum with the tide and never followed the fashionable trends. According to her, “an unfashionable item cannot in any way possible go out of fashion”.6 She did not attempt to keep with the cannon, but rather the natural course of the creative process that developed such Opera and Ballet Theatre as we now know it. Maybe we shouldn’t think of it as criticism, but just the inability of contemporaries to accept and appropriately evaluate this as one of the earliest and brave steps forward, where the late modernism started to gain more and more motives of the ‘post-’.

1 Vytautas Brėdikis, Vytautas Edmundas Čekanauskas, Vytautas Dičius and other architects have had the decoration of Knight of Architecture conferred on them for their merits to Lithuanian architecture.

2 From the interview with Saulius and Arvydas Bareikis, the architect’s sons, Vilnius, 7 October 2013, written by Indrė Ruseckaitė.

3 Algimantas Mačiulis, Tikras ir netikras pinigas interjeruose, in Literatūra ir menas, 3 December 1997, No. 49, p. 8.

4 Ibid, p. 9.

5 Marija Drėmaitė, Vaidas Petrulis, Jūratė Tutlytė, Architektūra sovietinėje Lietuvoje, Vilnius: VDA Publishers, 2012, p. 118.

6 From the interview with Saulius and Arvydas Bareikis, the architect’s sons, Vilnius, 7 October 2013, written by Indrė Ruseckaitė.

Straipsnis PDF formatu:

http://leidiniu.archfondas.lt/sites/default/files/95-102_essay_ruseckaite%20markejevaite.pdf